When Mahatma Gandhi refused to stand up in respect for the national song

On 27 December 1911, at the annual session of the Indian National Congress, Rabindranath Tagore’s freshly composed song Jana Gana Mana was performed, offering thanks for the divine benediction showered so generously on our country and our people. It had pleased Providence to guide Bharat’s destiny and to give succour to its suffering populace. The poet’s lyrics sang a paean to the expression of this divine glory that had many attributes—the Janaganamangaldayak, the Giver of grace, was at the same time the Janagana-aikyabidhayak—the One who crafted unity out of India’s religious and regional diversity. The eternal Charioteer was also the Janaganapathparichayak—navigating for His followers a most difficult path.

On 27 December 1911, at the annual session of the Indian National Congress, Rabindranath Tagore’s freshly composed song Jana Gana Mana was performed, offering thanks for the divine benediction showered so generously on our country and our people. It had pleased Providence to guide Bharat’s destiny and to give succour to its suffering populace. The poet’s lyrics sang a paean to the expression of this divine glory that had many attributes—the Janaganamangaldayak, the Giver of grace, was at the same time the Janagana-aikyabidhayak—the One who crafted unity out of India’s religious and regional diversity. The eternal Charioteer was also the Janaganapathparichayak—navigating for His followers a most difficult path.

Patan-abhyudaya-bandhur pantha, jug-jug dhabita jatri

The gender of this divinity is uncertain. The janaganadukhatrayak appears in feminine form.

Duhswapne atanke raksha korile anke Snehamayee tumi mata.

A song that so brilliantly fuses together an invocation to divine sovereignty with an intimation of popular sovereignty may seem with hindsight to have been a natural selection as a national anthem. Yet there is reason to ponder how Tagore, a patriot who was a powerful critic of nationalism, came to be accepted as the author of two national anthems of India and Bangladesh.

When Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose inaugurated the Free India Centre in Europe on 2 November 1942, the green, saffron, and white tricolour of the Indian National Congress was adopted as the national flag. Jana Gana Mana Adhinayak Jaya He—was chosen by Netaji as the national anthem—a choice that would be ratified by the Indian constituent assembly after Independence. He had played a key role in resolving the controversy surrounding the later verses of the other song, Bande Mataram, in 1937. He was open to considering Muhammad Iqbal’s song Sare Jahan se Achha Hindustan Hamara—proclaiming the excellence of India compared to the whole world—but in the end the decision was in favour of Tagore.

Dinendranath Tagore had written down the musical score of Jana Gana Mana in 1918. An elaborate orchestration of the song was done in Hamburg, Germany, in September 1942. On the occasion of the inauguration of the Deutsche-Indische Gesellschaft in Hamburg on 11 September 1942, a German orchestra played for the first time Tagore’s song as India’s national anthem. In 1971, Krishna Bose found the bill for the orchestration of Jana Gana Mana in the archives of Hamburg’s Rathaus. It had cost 750 Reichmarks.

Bose spoke of the bonds of poetry and philosophy between the two countries at the function. He did not neglect to mention how Tagore’s visits to Germany in the 1920s had strengthened cultural ties between the two countries. Netaji made his final public appearance in Berlin at a big ceremony to observe Independence Day on 26 January 1943, before his epic submarine voyage to Asia. The Independence Pledge of the Indian National Congress was read out. Berlin’s Radio Orchestra played Jana Gana Mana as India’s national anthem with great panache. Those in India who listened clandestinely to the broadcasts of Azad Hind Radio were enthused to hear it.

The Azad Hind government proclaimed by Netaji in Singapore on 21 October 1943 inculcated a spirit of unity among all Indians with a subtle sense of purpose. Jai Hind was chosen from the very outset as the common greeting or salutation when Indians met one another. Hindustani, an admixture of Hindi and Urdu, written in the Roman script, became the national language, but given the large south Indian presence, translation into Tamil was provided at all public meetings. A springing tiger, evoking Tipu Sultan of Mysore’s gallant resistance against the British, featured as the emblem on the Tricolour shoulder-pieces on uniforms. Gandhi’s charkha continued to adorn the centre of the tricolour flags that Indian National Army soldiers were to carry in their march towards Delhi. A simple Hindustani version of Tagore’s song Jana Gana Mana Adhinayak Jaya He became the national anthem.

As a Bengali, Netaji went out of his way to ask Abid Hasan to get the national anthem rendered in the national language of India. The lyricist Mumtaz Hussain composed the Hindustani song in three verses rather than five and Ram Singh Thakur wrote down a band score based on the original tune. Mumtaz Hussain did not attempt a translation, but sought to capture the spirit of Tagore’s song. Jaya He naturally became Jai Ho, long before AR Rahman made Jai Ho famous the world over. The first verse that mentioned several place names bore a strong resemblance to the Bengali lyrics.

A comparison of the verses evoking unity gives a clear sense of the similarities and differences between the Bengali original and the Hindustani version.

Aharaha taba ahwan pracharita, shuni taba udar bani

The Azad Hind version went thus:

Sab ke dil me preeti basaye teri mithi bani

In 1911 the British moved the capital from Calcutta to Delhi. Little did our colonial masters know that in the same year a song had found utterance in this city that would be acknowledged in Delhi as the national anthem once the tricolour replaced the Union Jack. But the song did not travel along the Grand Trunk Road from Calcutta to Delhi. It traversed Patan-abhyudayabandhur pantha—the entire global itinerary of India’s struggle for freedom—to eventually find its home in every Indian heart.

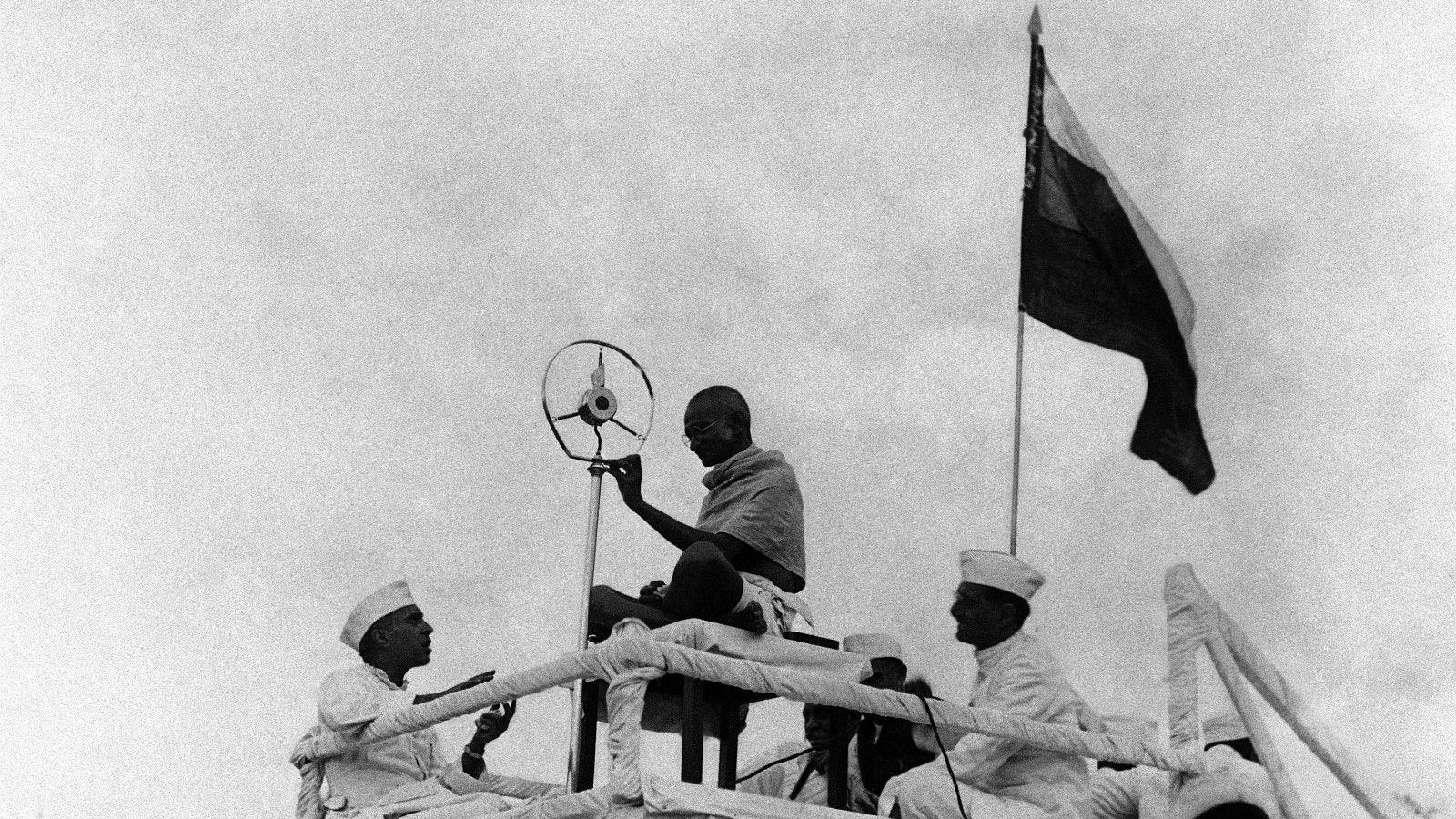

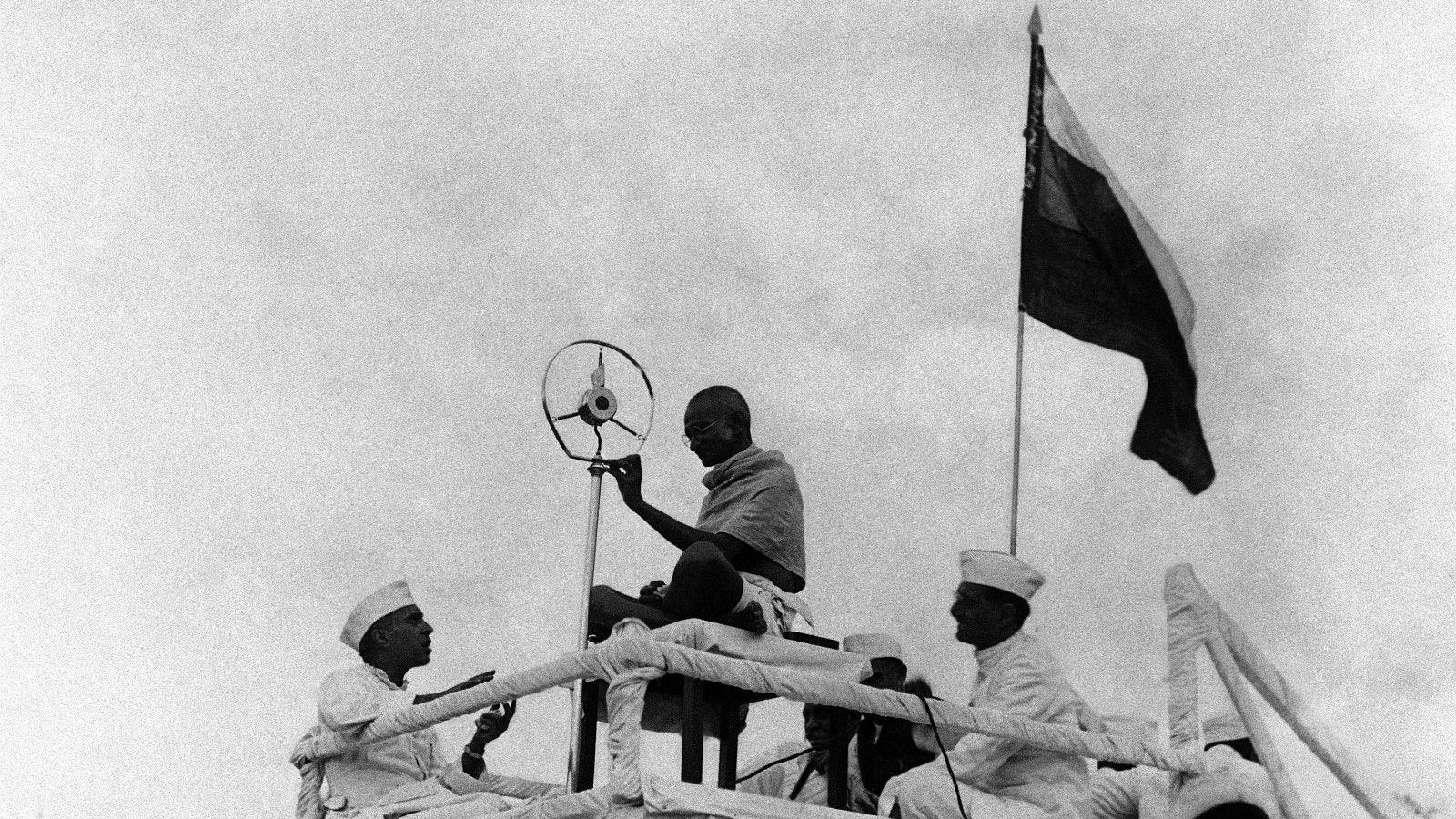

We can only speculate on how Tagore would have felt about the November 2016 order compelling Indian citizens to stand to receive divine benediction for their country. But history has recorded Gandhi’s perspective on the matter. Soon after Independence and Partition as Bande Mataram was sung at his prayer meeting on 29 August 1947, in Calcutta, Hindu and Muslim leaders on the stage including Suhrawardy stood up to show their respect along with the rest of the audience. The Mahatma remained in his characteristic seated pose. He was firm in his belief that standing erect in reverence for a national song was a Western custom, not in tune with Indian culture.

Excerpted from Sugata Bose’s book The Nation as Mother and Other Visions of Nationhood with the permission of Penguin India. We welcome your comments at [email protected].