The stories of three families’ new beginnings after the dark days of Indian partition

The partition of the Indian subcontinent was catastrophic for the over 10 million people caught up in the turmoil of new borders, displacement, and the horrors that plagued those on their way to new homes. But there were a few silver linings.

The partition of the Indian subcontinent was catastrophic for the over 10 million people caught up in the turmoil of new borders, displacement, and the horrors that plagued those on their way to new homes. But there were a few silver linings.

In 2016, I researched Britain Asian recollections of partition to write a play, Silent Sisters. The play is being performed again in November to mark 70 years since partition in August 1947.

I spoke to 52 people in workshops and individual interviews. It became evident that the pain, loss, and restlessness of forced movement to either Pakistan or elsewhere in India played a big part in families’ decisions to migrate overseas. The turbulence also spurred female survivors from conservative families to pursue educational and vocational careers that they would never have otherwise entertained.

Restless spirits

As a young man, he had escorted the future premier of Pakistan, Mohammad Ali Jinnah, to a meeting with India’s leader, Jawaharlal Nehru, Viceroy Louis Mountbatten, and the man tasked with drawing the lines of partition, Cyril Radcliffe.

She told me that partition went right through her father’s village in the Gurdaspur district of India’s Punjab province. “When I approached my father about it, he found it very difficult to talk about it,” she said. “But he did manage to bring out a full poster size photograph of the palace he grew up in.”

Sùna Al-Husainy’s paternal family were Muslims, descendants of a 13th-century Sufi saint, Hazrat Imam Ali Shah Sahib. His shrine is the Makkan Sahrif, now looked after by a Sikh octogenarian, Gurcharan Singh, in India.

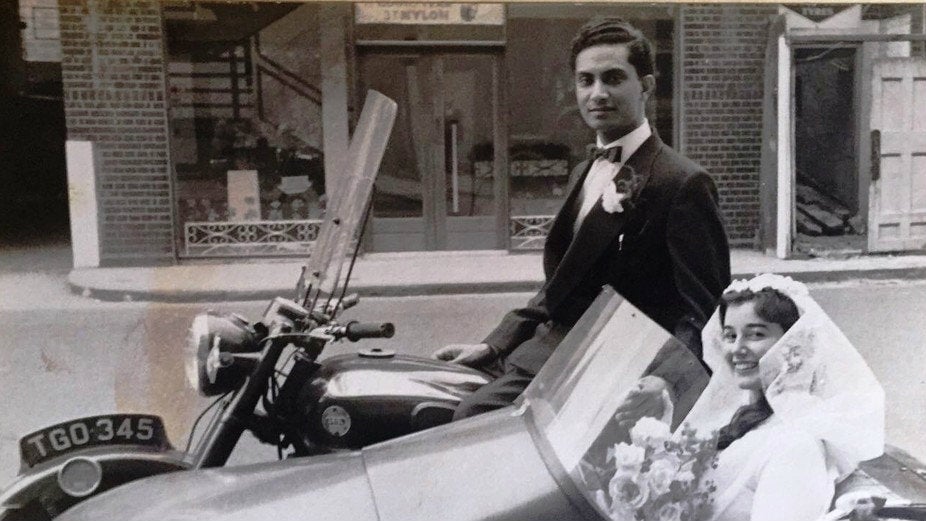

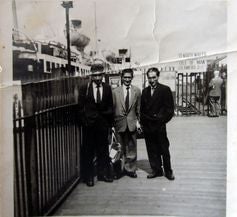

After partition, Saad Mahmood Al-Husainy moved to Lahore in Pakistan. As the eldest of six, he was expected to take the role of a Sufi pir or master. Instead, in a bid to escape his sense of political despair and memories of the atrocities that he had witnessed, including the beheading of his household servants, he made the decision to leave for Britain.

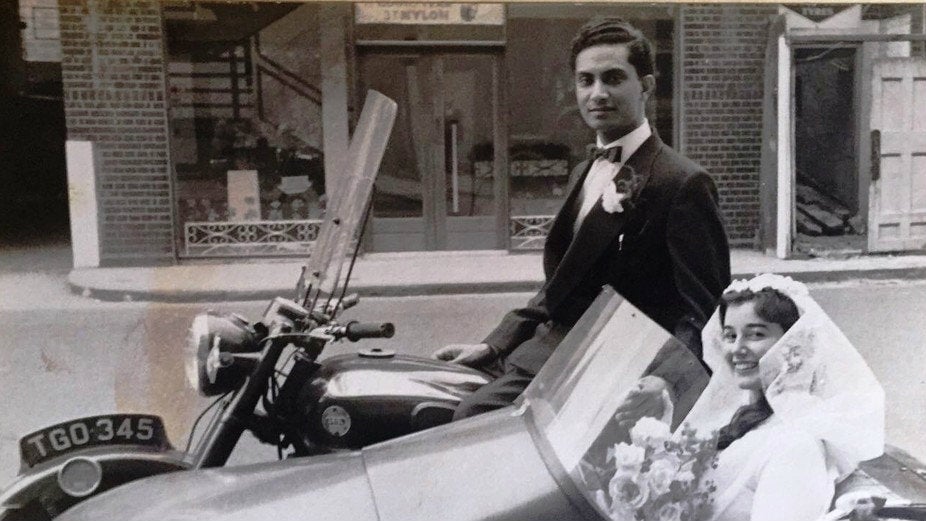

He enrolled at the University of Birmingham in the late 1940s to study medicine. There, at a poetry recital of the Sufi saint, Jalal al-Din Muhammad Rumi, he met an Irish woman, Colette O’Neill, who was training to be a teacher. They fell for each other, not least due to their love of poetry, and within three months, had got married.

Creative impulses

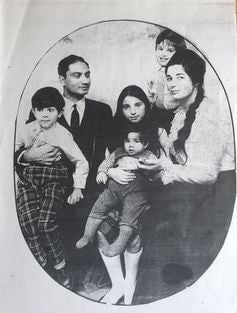

Siraj-Ud-Din was the maternal uncle of Javed Khan, one of the actors in Silent Sisters. He was a photographer living in the north-eastern Indian state of Bihar. In 1947, photographs were among his few belongings as he abandoned his home to sail with his extended family to the new nation of Pakistan. One of Siraj-Ud-Din’s pre-partition photographs was of female relatives in their former home in Bihar.

Another was taken around 1949 in their new home in the Punjab province of Pakistan.

Such photographs showing the resilience of ordinary refugees were a rarity. Khan reflected:

We were lucky to have these pics. Mamu [uncle] ended up having a photo studio in Karachi. I remember it—where he did portraits and 10 by 8 lobby pics for cinemas. My dad helped him with hand-coloring them among several other jobs.

Packed with hopes of having a better life in the former colonial heartland than in Pakistan itself, Khan’s family went to live in Yorkshire. In 1977, inspired by the artistic talents of his maternal relatives, Khan headed south to pursue a career in fine art prior to acting.

New horizons for women

Kaunain Rahman, a postgraduate student who attended one of the workshops for Silent Sisters, attributed her studying at the University of Sussex to fateful decisions made by her female ancestors. During the turmoil of partition, her great grandparents refused to move from Delhi. Like many other minorities who had befriended their neighbours, they were under the belief that they would be protected from any communalist attacks. But this was not to be. One night, marauders arrived en masse at their gates:

My great grandfather had his hunting rifle ready. And he had six daughters. If the mob breaks through, then he was ready to shoot and kill his daughters because he didn’t want them to be raped and then killed. It was only because my great grandmother’s brother-in-law had connections with politicians that they were airlifted out in the nick of time.

After their spectacular escape, they moved to Calcutta (Kolkata) with hardly anything to their name. Still, it spurred a new lease of life particularly for the women. She told me:

I’m sitting here today because of the decisions my great grandmother had made at that time. She had a few gold bangles. She sold all of them. And instead of keeping them for her daughter’s dowry or for food or for shelter, she put her daughters into schools. And those daughters went on to become successful women in their own respective fields. And then their daughters, and their daughters, well, one of them is me!

And so out of great devastation came incredible courage and new beginnings as partition survivors spread their wings far and wide.