A former US senator who called out Pakistan’s duplicity wants it treated like North Korea

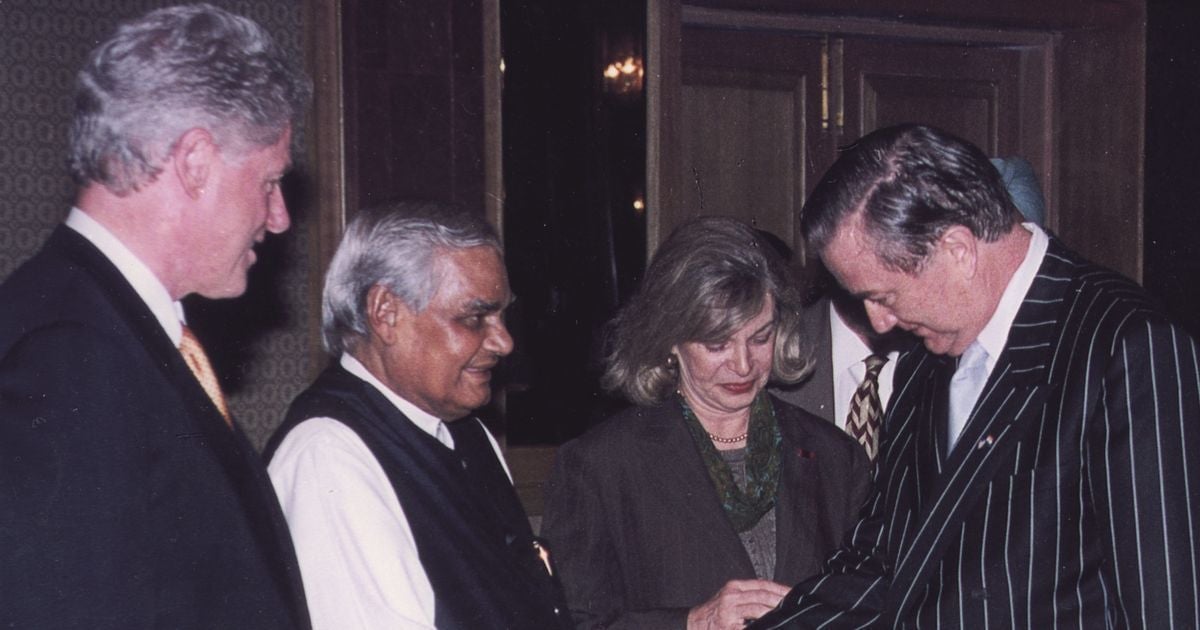

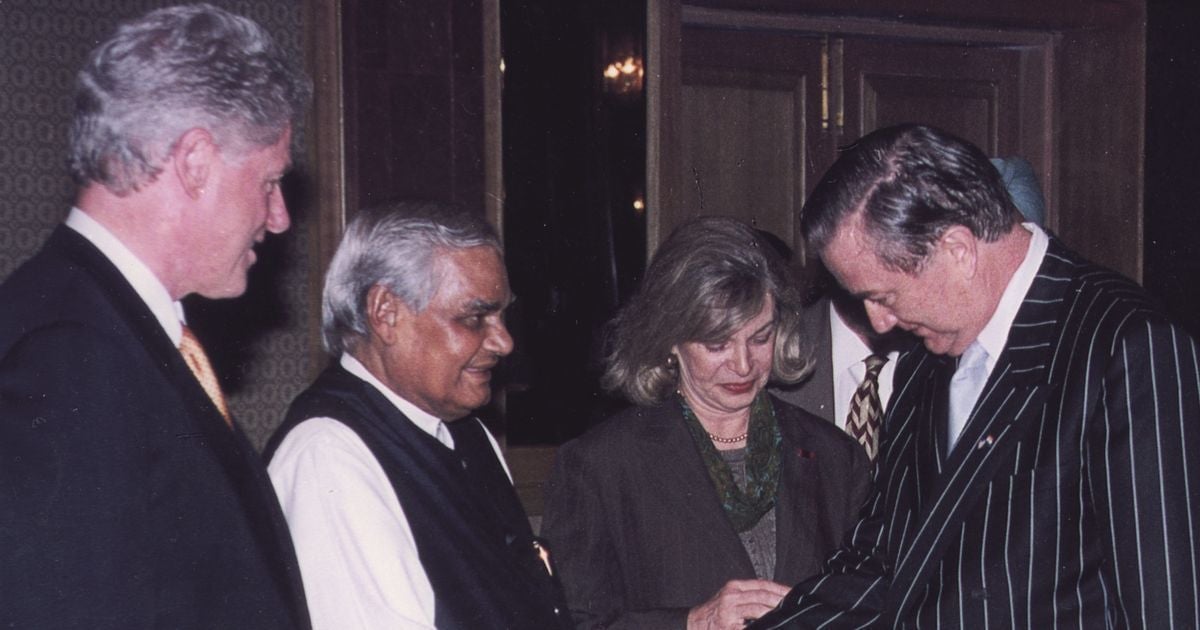

In the history of Indo-US relations, former United States senator Larry Pressler is a rarity. The US has, in general, been a staunch ally of Pakistan, providing it plenty of money, support, and arms over the last decades. Pressler is one of those few American politicians who has openly criticised this arrangement, which he argues only benefits American arms dealers, who fund many US politicians, and Pakistani generals, while making the world more dangerous for everyone else.

In the history of Indo-US relations, former United States senator Larry Pressler is a rarity. The US has, in general, been a staunch ally of Pakistan, providing it plenty of money, support, and arms over the last decades. Pressler is one of those few American politicians who has openly criticised this arrangement, which he argues only benefits American arms dealers, who fund many US politicians, and Pakistani generals, while making the world more dangerous for everyone else.

In the 1980s, the senator became famous in south Asia as the sponsor of the Pressler amendment, a piece of legislation that banned most US economic and military assistance to Pakistan unless the American government certified that Islamabad was not trying to develop a nuclear bomb—which it was secretly doing through the 1970s.

Although US presidents often saw the Pressler amendment as an impediment, it did bring focus to America’s sponsorship of Pakistan’s duplicitousness, usually in using funds and arms on the Indian border rather than the Afghan one. Pressler’s involvement with the legislation made him an object of hate in Pakistan, but also helped develop the senator’s interest in India, which had first begun in his college years.

In Neighbours in Arms, Pressler describes his younger days as a rural kid who somehow made his way up the American political ladder, only to frequently come up against a supercharged military-industrial complex which he dubs “the Octopus” and gives an account of the Pressler amendment and its aftermath. Below, excerpts from an interview with Pressler:

What advice would you give a young senator, from outside the beltway, if she were entering the Senate with the hope of fighting the military-industrial complex today?

This is what I would tell her: You are fighting for a cause and for your country. That is what serving in the US Senate is all about. The military-industrial complex is a necessary evil—to a certain extent. However, you must protect yourself against the corruptive influence of the “Octopus,” which is my new word to describe the great-grandchild of the military-industrial complex, that pestiferous beast that president Eisenhower named in his farewell address to the American people in 1961.

The “Octopus” is the Pentagon, the arms contractors, the law firms, the consulting firms, and the system that has come to dominate Washington DC. You must be transparent in your interactions with the “Octopus” and you must be an honest broker with all its tentacles in Washington. As I have outlined in my book, these tentacles are myriad, long, and strong. It won’t be easy to resist getting sucked in by the “Octopus”—its money and its influence—but you have to do it. Otherwise, it will strangle you!

Do you think, if you had not ended up on the foreign relations committee, you would have had as much of an interest in US-India ties as you ended up with?

Yes. I was first enchanted with India when I visited the country during college on a trip to conduct research for a thesis. I was mesmerised. But I was also struck by the nation’s abject and choking poverty. So, even if I didn’t have the privilege of working with India as a senator, I think I would have figured out a way to get over there and attempt to help the Indian people.

My early assignment as the chairman of the arms control subcommittee of the Senate foreign relations committee was somewhat providential. It gave me an opportunity to become a footnote in the history of India-Pakistan-US relations and to make a real difference to the Indian and Pakistani people.

You advocate a closer, “super” alliance with India and call for the harnessing of the “Octopus,” but does it not seem appropriate that India—which thankfully spends more on infrastructure than defence—is wary of being sucked into the military-industry complex?

Absolutely. I feel terrible that India is rapidly developing an “Octopus” similar to what the US has. This is a great dilemma for both countries. We both need a strong national defence and we must fight the terrorist threat, but we can do so with leaner, more efficient military budgets and with fewer overlapping intelligence agencies.

We need to restore the basic decision-making authority within our democratic institutions (the state department, the White House, and the Congress) rather than have them constructed in consulting and law firms. In my opinion, this can be achieved with greater citizen awareness and participation.

You speak of looking at the potential that religious organisations can play in diplomacy, but is there not a danger that they, too, will turn into non-transparent lobbyists, and worse, be accused of spreading governments’ agendas?

Yes, that is always a danger. We must advocate moderate thought within religious organisations and universities everywhere in the world. Religious organisations in the US run the gamut of political ideologies. Here in the US, we may wear our religious values on our sleeves a little too much, but that is how we achieve in-depth support and understanding. In my opinion, religious organisations in the United States will never become as corrupt as our lobbying firms, consulting firms, and law firms because we have laws that require these organisations to be much more transparent and to publicly disclose much more about their finances than the private consulting and lobbying firms do.

Religious groups are not usually a part of the “Octopus” and they do provide a leavening effect in our public policy.

Do you believe something like ABSCAM (a Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry into political corruption in the 1980s in which Pressler was the only US politician on tape to refuse a bribe) could even be carried out today, when much of the bribery implicit in the system seems to have become normalised and even legal?

We do have legalised bribery in the United States in the form of campaign contributions and payments to lobbyists. In my new book, I say the way to limit the “Octopus” is by getting lobbyists out of the fund-raising cycle.

During the early part of my career, this was done with cash payments. Our national newscaster, Walter Cronkite, once declared me a “hero” for flatly and quickly rejecting a bribe. I said “what have we come to if rejecting a bribe is heroic?” Today we still have too much money in politics. That is why I am now supporting a constitutional amendment that would limit campaign contributions and make them more transparent. But I believe these payments are now made through legalised methods. This is a dismal and cynical view, but I firmly believe we have essentially lost our democratic foundation and we need a “great awakening” of our citizens to restore it.

As the only public official to refuse bribery then, how do you see the standards being set by the current occupants of the White House?

I did not vote for Donald Trump, but he is my president now and I want him to be a successful one. However, I am bothered by the “management by chaos” that seems to dominate this administration. The “Octopus” seems to be growing even bigger because of a lack of oversight by the Trump administration.

What prospects do you see of the Trump administration moving forward on the US-India relationship? Will the state department be able to maintain any semblance of coherent policy?

Yes. Even though the Trump administration seems to manage by chaos, his appointees on south Asia might advocate for an even stronger US-India relationship than president Obama forged. Ironically, the Trump administration could be one of the best friends the Indian people could have. I urge in my book and have urged the Trump administration to declare Pakistan a terrorist state.

Why do you believe public opinion in the US is still not very clear on Pakistan, the way it is with Iran or North Korea, when it comes to talking about dangerous states?

That is a very complex but true statement. Our “Octopus” has basically created and financially supports Pakistan. It is the favoured nation of the Pentagon because Pakistan has allegedly helped us fight terrorists in south Asia. Everyone knows this is false, and that Pakistan harbours terrorists within its borders—and within its own military and the ISI. It is a corrupt and, by many estimations, a failing state. My crusade for my twilight years is to ensure Pakistan is placed in the same category as Iran and North Korea.

The current policy review being spearheaded by Lisa Curtis, the new senior director for south and central Asia at the White House national security council, might result in designating Pakistan a terrorist state. As I have said, the Trump administration might turn out to be one of India’s best friends.

What would it take to slay the “Octopus”?

It will take citizens waking up to what a tragedy is befalling our democracy. We need another great “awakening,” a realisation that elections do count and that everyone needs to participate. Also, as I recommended in my book, we must take lobbyists out of the fundraising “chain” in political campaigns. That is to say, lobbyists should be prohibited from raising money for political candidates, political action committees (or PACs), and independent expenditures. Lobbyists would still be able to lobby on the merits of legislation, but they would not be able to raise money to influence legislators. This would break the power of the “Octopus.”

Is there still space in American public life for other Larry Presslers—politicians willing to be independent of their parties and take unpopular public stands?

Yes, there is hope. But it is going to take a much greater effort on the part of the average citizen. Mankind today is locked in a huge arms race that will only result in possible war and more poverty. India and the United States are both a part of that. I have great hope for the future but it will take a strenuous effort from citizens in both countries to reclaim democracy.

In the US, without the support of one of the two major political parties (Democratic or Republican) backing them, independent candidates will likely not be effective nor very powerful. However, more and more people are identifying as independents. We will have to resolve this contradiction. I ran for the US Senate—once again—in 2014, as an independent candidate and I had no political party backing me, only individuals. Once I gained some traction with voters, the political money machines of the Republican and Democratic parties in Washington decimated me with negative messaging. Thus, we must find a way to channel and harness the great under-the-surface, independent surge in the USA. Perhaps others will run as independent candidates in the future and succeed. If we could get five independents into the US Senate, it might have the fulcrum effect of breaking our political deadlock.

It might break the “Octopus.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].