The glaring problem keeping “Make in India” from attaining the success of “Made in China”

India is chasing some serious manufacturing dreams, looking to increase its share in the country’s GDP from 16% today to 25% by 2025. This dovetails with prime minister Narendra Modi’s fairly successful Make in India campaign.

India is chasing some serious manufacturing dreams, looking to increase its share in the country’s GDP from 16% today to 25% by 2025. This dovetails with prime minister Narendra Modi’s fairly successful Make in India campaign.

However, if manufacturing has to succeed, wages must rise so that the quality of workforce attracted to and retained in the sector improves.

A report (pdf) prepared by the NITI Aayog, a policy body that advises the Indian government, and IDFC Institute, a Mumbai-based think-tank, reckons that “workers in manufacturing in India are overwhelmingly stuck in low wage jobs,” besides being “disproportionately employed.”

In China, average hourly wages for factory workers hit $3.60 in 2016, according to market research firm Euromonitor, which is more than five times the hourly manufacturing wages in India.

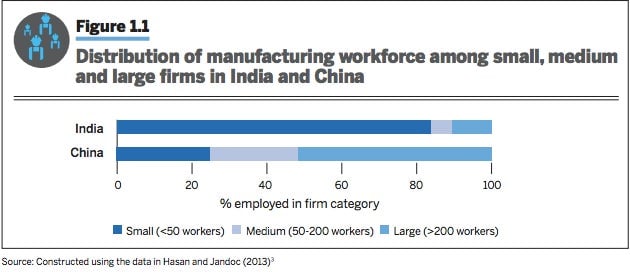

The NITI Aayog-IDFC Institute report underlines its point by making its own comparison with China. While small-sized manufacturing firms employ 84% of the workers in India, in China it is the medium-and large-sized ones that employ 75.1% of the workers, the report says.

“As a large, labour-abundant economy, one would expect India to have a comparative advantage in large-scale, labour-intensive manufacturing. Yet, India has not done well in this sector. Instead, successful sectors in India have been either capital or skilled labour-intensive, and most prominently include auto, auto-parts, two-wheelers, automobiles, engineering goods, petroleum refining, pharmaceuticals, and software,” the report says.

The Modi government had recently approved a new labour code on wages, which is expected to significantly improve the ease of doing business and ensure a minimum wage to all. However, even that may not be enough, as the NITI Aayog believes:

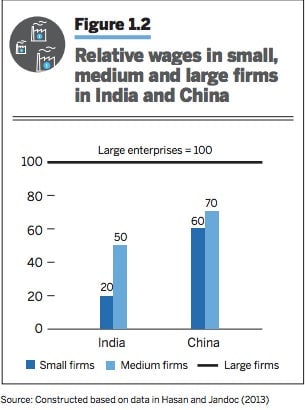

“Why are the wages in small and medium enterprises in India so much lower than in China? A plausible hypothesis is that because large enterprises disproportionately participate in the highly competitive world markets, they must constantly innovate and improve efficiency to stay competitive. This makes them far more productive than small and medium enterprises. But the presence of a sizeable number of large enterprises also creates an ecosystem in which small and medium firms must compete intensely. They either become ancillaries of the demanding large enterprises or must compete against them. This helps raise their productivity as well. The end result is relatively high wages even in small and medium enterprises in the presence of large enterprises.”

So, wages across small enterprises in China are almost 60% of that in its large enterprises. Whereas in India, this figure stood at just 20%. “These figures actually underestimate the difference once we recognise that the real wages in large enterprises in China are significantly higher than those in India,” the report said.

Clearly, pay well and manufacture more is the mantra.