In India, it’s the media and not e-commerce that desperately needs a Jeff Bezos

On the day that India celebrated her 70th Independence Day, The Guardian newspaper of London published a damaging story about the Adani Group. The publication had got hold of an Indian customs intelligence notice alleging that Rs1,500 crore ($235 million) had been siphoned off to tax havens by the Ahmedabad-based business house. The group’s chairman, Gautam Adani, is understood to be a close confidant of prime minister Narendra Modi.

On the day that India celebrated her 70th Independence Day, The Guardian newspaper of London published a damaging story about the Adani Group. The publication had got hold of an Indian customs intelligence notice alleging that Rs1,500 crore ($235 million) had been siphoned off to tax havens by the Ahmedabad-based business house. The group’s chairman, Gautam Adani, is understood to be a close confidant of prime minister Narendra Modi.

Newslaundry, a media satire and criticism portal, observed that barring two independent digital outlets, India’s leading pink papers had entirely given the story a miss.

Adani is a feared man in the country today. In the weeks prior to the Guardian revelations, his group had sent legal notices to the individual trustees of The Economic & Political Weekly over an article by then editor Paranjoy Guha Thakurta. The write-up showed the Modi government having surreptitiously tweaked the rules governing special economic zones, resulting in a Rs500 crore bonanza for Adani’s companies.

The trustees of EPW, among India’s oldest and most respected peer-reviewed academic journals, got the story removed from the magazine’s website, fearing a legal backlash. Thakurta resigned after having been at the helm for barely over a year. The mainstream media, again, chose not to follow up on what were sensational allegations against one of India’s leading publicly-listed corporations.

Censorship has existed in India for a long time, and under all political dispensations. But in the three years that Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) has been in power, the suppression of the press has assumed a frightening intensity.

Channels seen as being critical of the government have been raided, and unflattering stories about politicians are being taken down with alarming regularity. The alleged duplicity of corporate entities such as the Adanis, meanwhile, have been made invisible by a glaring omission bias. Had this bias existed just a few years ago, the same media wouldn’t have unearthed the myriad instances of crony capitalism that played a part in bringing down the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance government in 2014.

A cocktail of problems

At the centre of this unfolding crisis in the Indian media is a potent cocktail: dodgy ownership structures, a broken financial model, disruptive digital forces, and an adversarial government—all of which call for an expedient rescue of India’s fourth estate.

While big chunks of the country’s regional press are controlled by politicians, large national media outlets have been bought out by corporations like Reliance Industries and the Aditya Birla Group over the last five years.

These entities have interests in important sectors of the economy such as oil & gas, cement, energy, infrastructure, and telecommunications. This necessitates a more than amiable relationship with the country’s government and its elephantine bureaucracy. Without such cordiality, the needle doesn’t move on the byzantine clearances one requires to put up large projects in India.

Such is the relationship between the government and big business in the country that any media company controlled by these corporations, through equity or even advertising budgets, is compelled to become the proxy voice for the party in power. Meanwhile, the government itself holds considerable influence—it spent nearly Rs1,200 crore (over $187 million) advertising welfare schemes alone in 2015-16, a 19% increase from the previous financial year.

Add to this the fact that the Indian news market today lacks a viable financial model that lets companies monetise through higher subscription revenue. Currently, subscription accounts for between a paltry 5% and 20% of the total revenue for broadcasters, as compared to about 50% for the US equivalents such as CNN.

So, much as Indians love to complain about their news, the sad truth is, they hate to pay for it.

Under these circumstances, then, the one demonstrated way in which press autonomy can be restored is through sustained patronage.

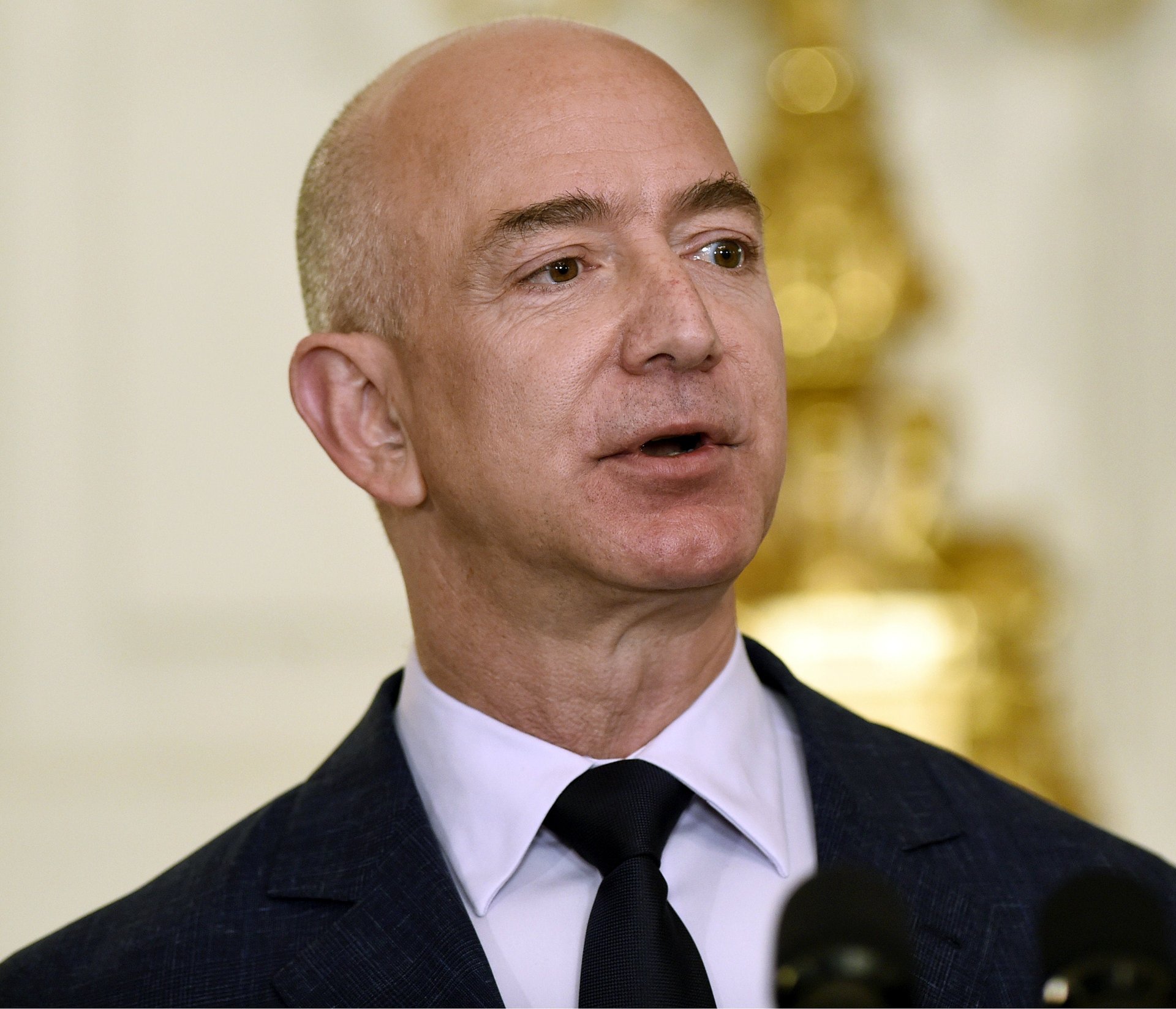

India’s media needs a benign, moneyed private proprietor who can take a long view on things. Someone not seeking instant profits yet able to function without having to curry favour in the corridors of power—an equivalent of Jeff Bezos. The results of what such an intervention could do are visible from the Amazon founder’s remarkable turnaround story of the ailing Washington Post, which he bought about four years ago for $250 million.

Finding an Indian Bezos

In Donald Trump’s America, the socio-political environment that the media faces is almost comparable to that in Narendra Modi’s India: a distrustful conservative government, unfavourable public opinion, and a backlash against liberal values.

But unlike India, where the press has been emasculated by adversarial forces, the deep pockets of Bezos have emboldened the Washington Post to assume the position of a commendable opponent of the powers that be. It’s also helped the paper chart a dramatic revival, reinventing itself from a flailing legacy newspaper to an innovative digital media and technology company at the very cutting edge of journalism.

In an incisive piece for The New York Times, James B Stewart referred to this editorial and financial resurrection of the Post as “little short of astonishing,” adding that its “recent scoops have often shaped the national conversation” in America.

In India, where Bezos’s Amazon has upended the local e-commerce industry, such fearless support to a media house would dramatically alter the present milieu of diffidence, wherein—to use an Emergency-era admonishment of the media by, ironically, veteran BJP leader Lal Krishna Advani—journalists are often seen crawling when asked to bend by their corporate bosses.

Of course, there are reasons for Bezos to not want to have anything to do with news media. After all, foreign direct investment in broadcast media is capped at 49%. There is little incentive for Amazon to scuttle its chances in India by entering a line of business where the government, prone to policy reversals, is the chief adversary.

But there are many Bezos-equivalents of our own who could step in to save the day—the Premjis, the Nilekanis, the Murthys—all well-respected mogul-philanthropists from India’s own Silicon Valley, with impeccable reputations of personal integrity and an established track record in giving.

At a time when both the diminutive opposition and the media have been disempowered to this extent, they need to step forward, individually or collectively, with their money might, ingenuity, and staying power.

There have, no doubt, been baby steps in this direction. Last year, these Bengaluru billionaires launched the Independent & Public Spirited Media Foundation with a Rs100 crore corpus. But saving the world’s largest democracy from being silenced into submission will need a more extensive commitment. It may not promise immediate financial returns, but will go a long way in building social capital and help these tycoons craft a lasting legacy.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].