The Persian language has a rich history in India, but it’s slowly dying out

It is difficult to think of Persian as an Indian language today. Yet for hundreds of years, Farsi held sway as a language of administration and high culture across the subcontinent. It was brought in by Persiophile central Asians during the 12th century, and played a role very similar to the one English does in modern India. So, in the 17th century, when the Marathi Shivaji wanted to communicate with Rajasthani Jai Singh, the general of the Mughal army in the Deccan, they used Farsi.

It is difficult to think of Persian as an Indian language today. Yet for hundreds of years, Farsi held sway as a language of administration and high culture across the subcontinent. It was brought in by Persiophile central Asians during the 12th century, and played a role very similar to the one English does in modern India. So, in the 17th century, when the Marathi Shivaji wanted to communicate with Rajasthani Jai Singh, the general of the Mughal army in the Deccan, they used Farsi.

The elite of 19th century Bengal were bilingual in Farsi (Persian in English) and Bangla. Raja Rammohan Roy edited and wrote in a Farsi newspaper, and the favourite poet of Debendranath Tagore, Rabindranth’s father, was Hafez, a 14th century poet from Iran. So impactful was Farsi’s role that India’s largest language today, Hindi, takes its name from a Farsi word meaning “Indian.” With the coming of the Raj, English replaced Farsi, but pockets of the language still survive in India. This is an extract from the diary of a Persian teacher in Kolkata:

Kolkata diary

This is my third visit to Kolkata and I am still overwhelmed with joy to see the city flourishing culturally. Kolkata’s extreme paradoxes, an intellectual environment existing alongside deprivation, create a combination of joy and struggle. My most educated Indian friends are from Bengal. I can see many similarly educated people on the streets of Kolkata. Every day, on their way to work, these intellectuals walk past crowds of hawkers and people washing themselves under the municipal water taps. Everything is wet in the monsoon, yet water is still a relief for people who live in the street.

Kolkata does not show its reality to a tourist who only goes to the Victoria Memorial or Birla Mandir—the real Kolkata is on its streets. Part of this reality is also buried in the South Park Street Cemetery. This is where people like Sir William Jones (1746-1794), the founder of the Asiatic Society and the father of Orientalism, and Henry Louis Vivian Derozio (1809-1831) have been laid to rest.

I went to this cemetery in the heart of the city, on a weekend, along with a group of Farsi language students who were attending the summer school held in Lady Brabourne College. The students gathered next to Sir William Jones’s tomb and listened to their professor, who was explaining how Jones had served oriental studies during his short life in the city.

Persian and Bengali

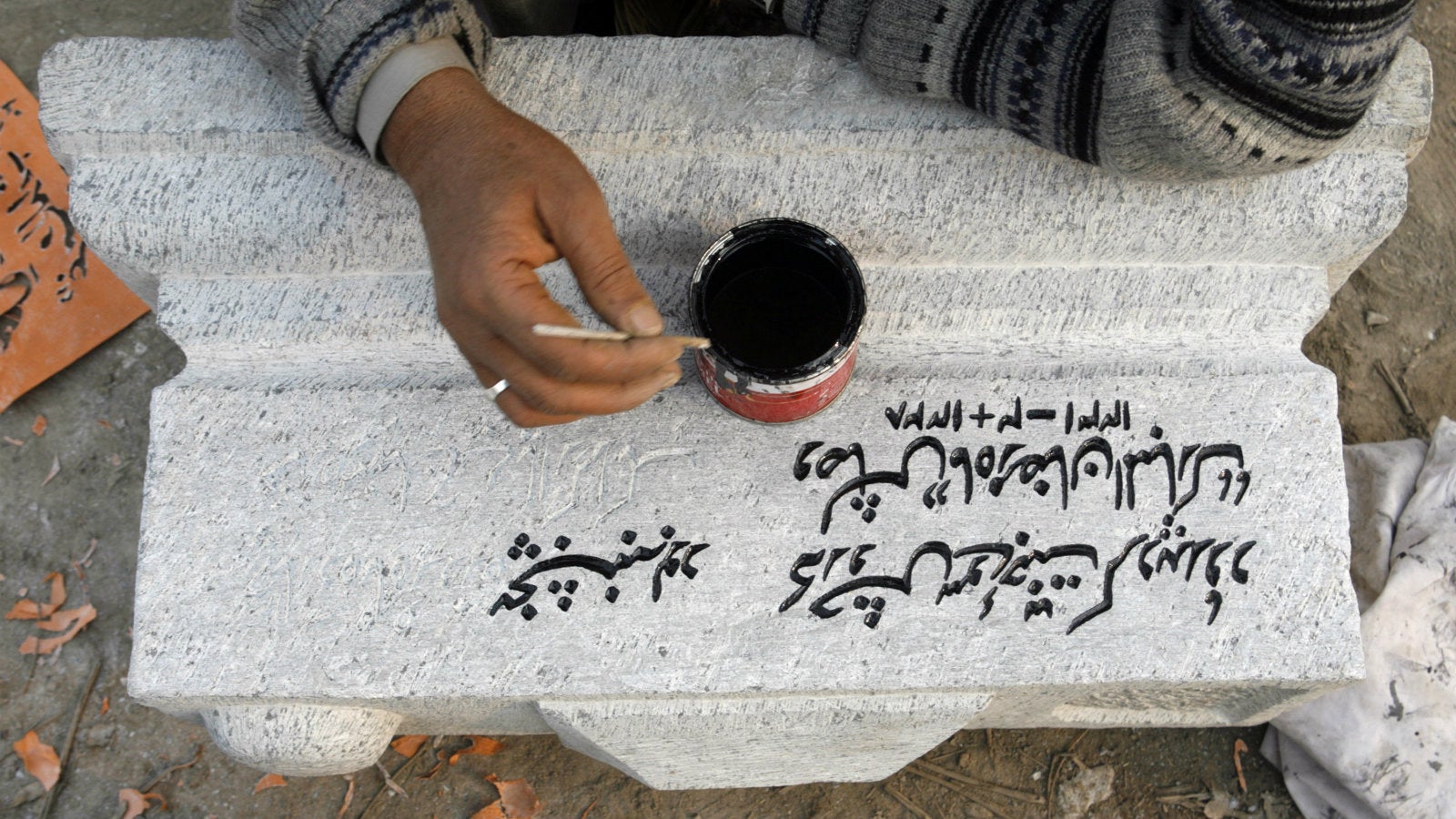

Looking for the city’s Persian legacies, the same group of students found their way to St John’s Church, where Farsi inscriptions are engraved upon the structure. They recount the life and death of people like Willian Hamilton, the surgeon who served the Mughal emperor Farrukh Siyar in Delhi. Farsi was a major language in the subcontinent for several hundred years. Despite Bengali having many words in common with Farsi, in Bengal, there are no longer any native speakers of Farsi.

It is still taught in a few schools of Kolkata as an optional subject. Some colleges, such as Lady Brabourne and Maulana Azad, have Farsi departments. Hearing the Farsi words coming out of their classrooms, it seems as though the Bengali tongue has forgotten how to pronounce Farsi words. The students could not read the inscriptions on St John’s Church, even though most were Muslims, familiar with Urdu.

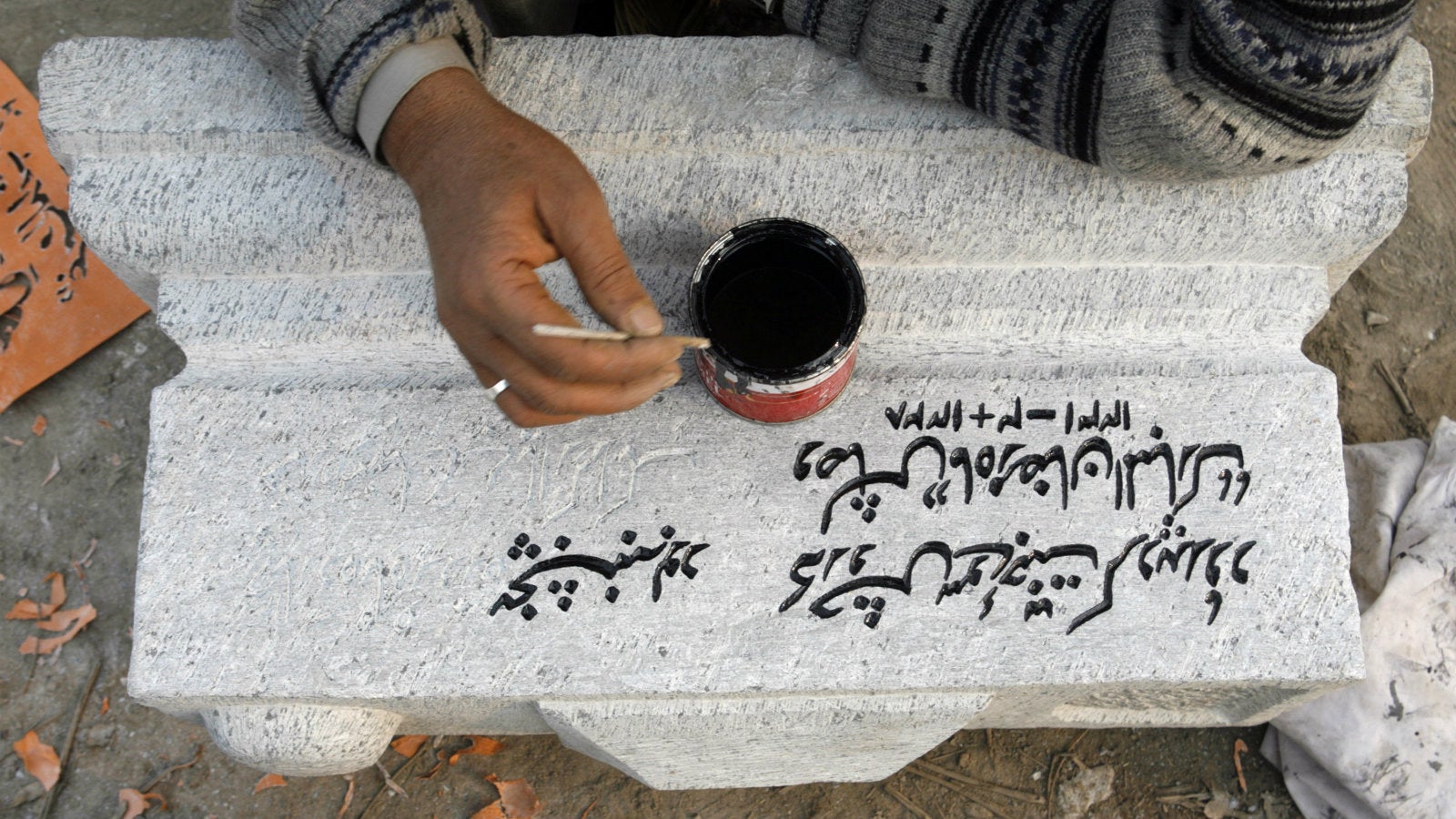

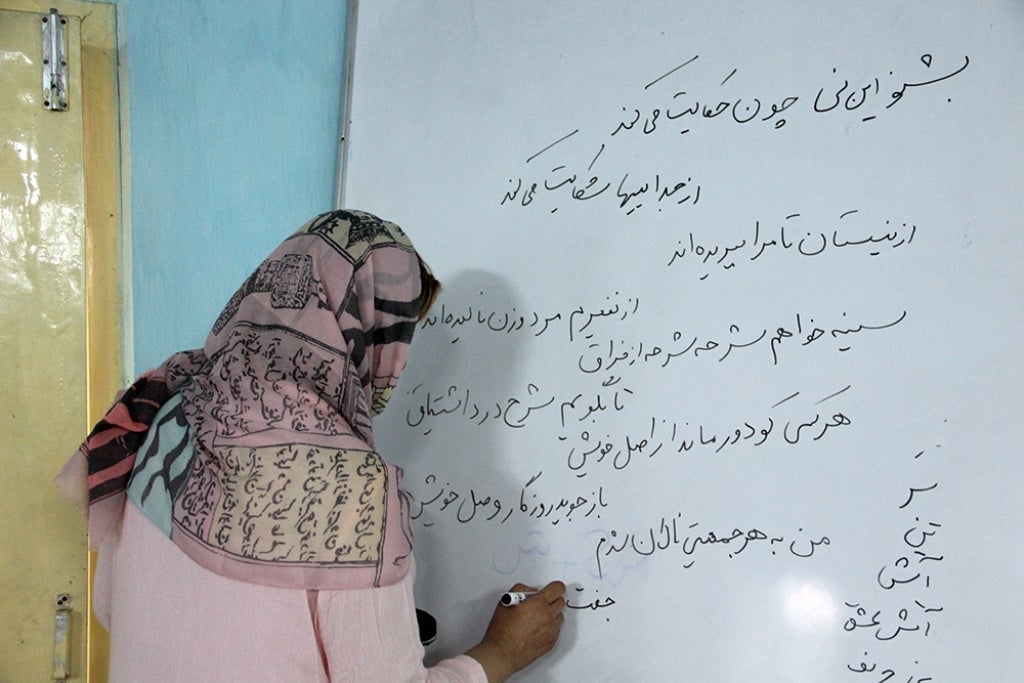

At a two-week summer school in Lady Brabourne College, organised by the Institute of Indo-Persian Studies, 54 students from various colleges in Kolkata had the chance to learn Farsi from native speakers for the first time. Some students could recite Farsi poems but as a native Farsi speaker, I could not grasp anything they said. The students in the Bachelor’s programme as well as some completing their Master’s had to go back to the Farsi alphabet, to learn its correct sound and to distinguish letters like “f” and “p,” which were being pronounced in a similar way due to their vernacular accent.

Next, they moved on to the formation and usage of simple and complex Farsi words, and reading out Farsi text in a proper Farsi accent. On the fourth day, they began memorising the ghazals of Hafez and Khusro and Iqbal. They also glimpsed the magnificent worlds of Firdausi, Rumi, Hafiz, Khusro, and others.

Considering things from a wider perspective, I wondered how this poetry might change their lives. Would an understanding of Sufism in Farsi poetry create better human beings? The literature may change their world outlook. But what is more solid? The grammar of a language or the rules of a society?

Tagore connection

I was teaching Farsi through films to familiarise students with the everyday life of Iran, and to improve their listening skills. To my surprise, I realised that the Farsi studies students did not know much about Iranian culture. They were not even familiar with well-known film directors from the country.

Some of my questions were answered at Rabindranath Tagore’s house, another location the Farsi students visited as a part of the extracurricular programme provided by the summer school. The house has been turned into a museum, and certain rooms have been used to depict the cultural interaction between Tagore’s home country and some of those he visited. Each of these rooms serves as a reflection on the cultural connections between India and the country visited by him. There is no room dedicated, however, to the Indo-Iranian cultural connections of Tagore—despite his having travelled to Iran twice in a two-year period. Considering such negligence of Indo-Iranian heritage, it is no wonder that the Iranian Embassy and the Iranian Cultural Centre in New Delhi made a minimal financial contribution to Kolkata’s Farsi summer school.

Promotion vs preservation

Iran might be the home of the Farsi language, but it is also spoken in countries like Afghanistan and Tajikistan. Despite having a claim over Farsi, the Iranian government does little to promote the language abroad. In a place like India, Farsi does not need to be promoted—it merely needs to be preserved. Most Farsi manuscripts lie unused and locked in Indian libraries and archives. The task of documenting, digitising, and preserving these manuscripts is beyond the capabilities of Persian Studies Centres in India.

The future of the Farsi language in India is ambiguous. Efforts are underway by the president of IIPS, professor Syed Akhtar Husain, to revitalise the language as well as Indo-Persian culture. Husain refers to the glorious era of Persian in the subcontinent, during which valuable books, records, and documents were produced. He said: “It is a pity that the current generations have kept themselves away from the vast treasure troves of Persian literature preserved in various libraries and archives in Bengal.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].