Indian NGOs are now suffering for not having groomed leaders over the years

A leadership crunch is crippling India’s non-government (NGO) sector.

A leadership crunch is crippling India’s non-government (NGO) sector.

Chronic negligence has led to a virtual absence of talent-nurturing in these organisations.

Nearly all (97%) of the 250 leaders from the sector surveyed recently considered leadership development vital to their organisations’ success, according to a study by Bridgespan, a US-based non-profit. This was echoed by 50 funders, too. Yet, over half the NGOs surveyed reported not having received any money towards this in the past two years.

“Pushed in part by donors to focus almost exclusively on delivering programs, NGOs…often shortchange themselves by under-investing in people,” Pritha Venkatachalam, the co-author of the study, titled Building the Bench at Indian NGOs: Investing to Fill the Leadership Development Gap, told Quartz.

This proves a hurdle particularly when NGOs try to “scale and sustain impact,” Venkatachalam said.

The number of NGOs operating in India are estimated to surpass three million but those having real-world, large-scale impact are few.

But the crunch is felt most acutely by those with over 50 full-time employees that ”realise they cannot rely on a single leader and must build a strong leadership bench,” according to Venkatachalam (see chart). As they begin to address the burning need for good top-level talent, confidence improves. So NGOs with over 100 employees fare better, according to the survey.

For the survey, leaders of 203 organisations of varying sizes rated on a scale of one to five how capable their organisations were across the four leadership-pipeline components: developing, retaining, recruiting, and transitioning.

Irrespective of sectors and size, half the organisations do not assess the leadership on the ability to meet future challenges and seize opportunities. In fact, 22% of them don’t asses the leadership at all.

Struggling to cope

The NGO sector talent pool is small and those vying for senior-level recruits are many.

Nearly 40% of NGOs surveyed by Bridgespan struggled to even enlist senior leaders. Their other big challenges were transitioning new recruits into their new positions and developing their leadership skills.

While leaders typically move from one NGO to another, over 30% of the organisations identified private sector for-profits as a primary source for senior talent, the study noted. There are, of course, tasks that require specific expertise from outside, like when an organisation begins using more technology.

However, outside hires are mostly burdensome. Discovering and onboarding new senior-level recruits can be an expensive affair.

Besides, moving from the private to the social sector can be daunting. “The problems the social sector is attempting to tackle are more complicated and intractable, whilst the resources are much more constrained,” Venkatachalam explained. ”Impact and progress are harder to measure and can take longer to see and the culture is very different.”

A sustainable solution to NGOs’ problems is to identify talent from within.

Hone at home

Potential in-house leaders are likely to be easier to retain. “They have institutional and stakeholder knowledge and are likely a good cultural fit with the rest of the team,” Venkatachalam added.

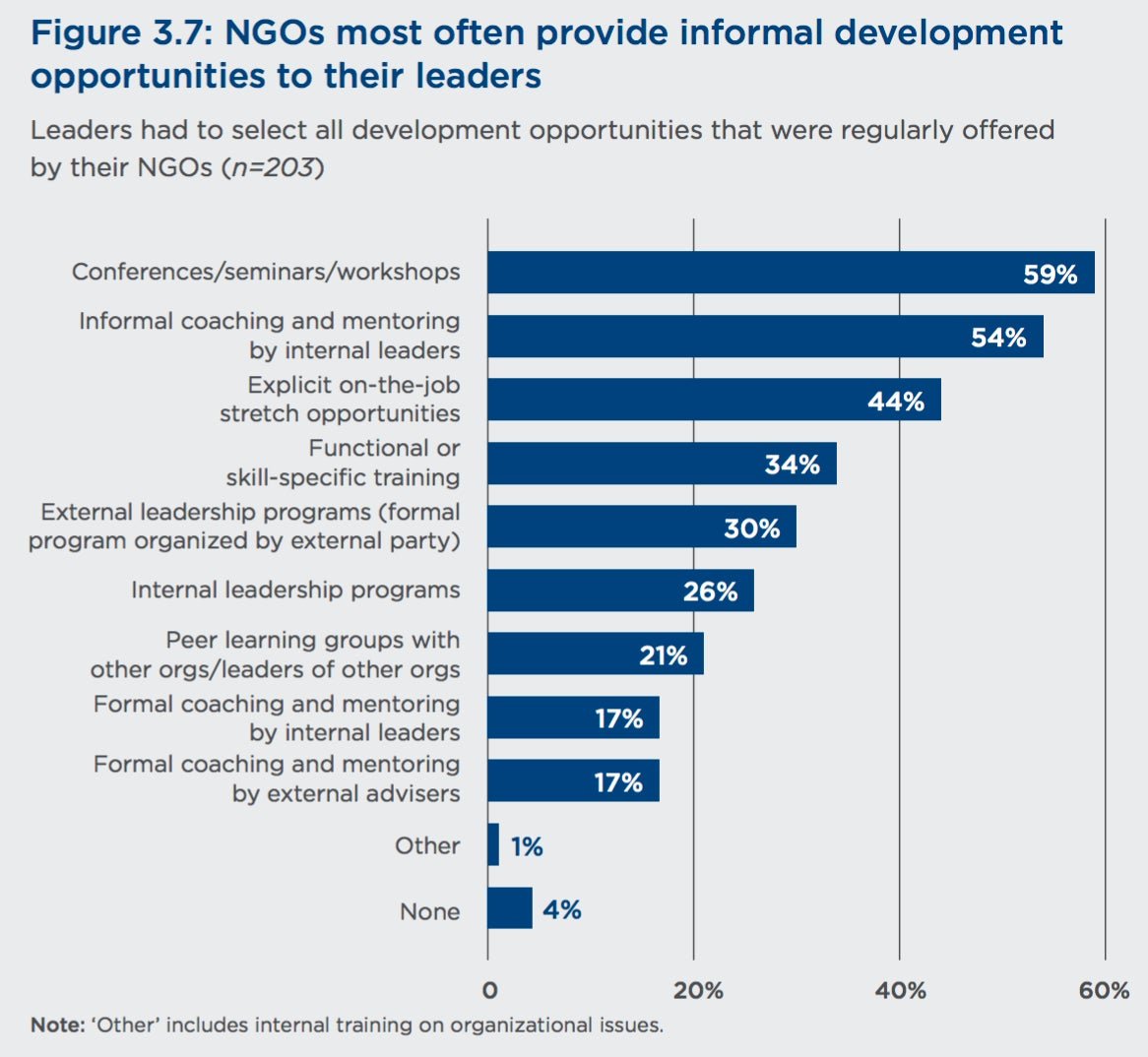

However, only 54% of NGOs coach or mentor internal leaders and mostly do so on an ad hoc basis. This is due to insufficient resources (both funding and tools), low awareness, and lack of prioritisation, the study notes.

A second line of leadership is key to avoid over-dependence on individual leaders (often the founders) and for succession plans, something that over half the NGOs surveyed haven’t given a thought to. Some, though, have come up with solutions such as following a two-CEO model or moving decision-making down the line to regional managers and others closer to the projects.

“There is no ‘one-size-fits-all’ magic bullet for leadership development,” Venkatachalam says. But deeply investing in talented senior staff has shown to bear fruit as “greater ownership, mission alignment, and institutionalised learning across levels of the organisation.”