Why are small businessmen in Gujarat turning to mutual funds and fixed deposits?

Two major trends are playing out in Gujarat’s economy.

Two major trends are playing out in Gujarat’s economy.

On one hand, small industrial units are shutting down. This is not a recent development. Micro, small, and medium units in the state started getting into trouble about five years ago, well before the central government demonetised high-value currency notes in November and introduced the Goods and Services Tax (GST) in July. As Scroll.in reported from Surat, several factors were at work—rising imports from China, the entry of bigger players with greater economies of scale, and government policies such as import duties that favoured bigger companies over smaller ones.

On the other hand, financial investments have boomed in Gujarat. Two years ago, a sharebroking firm in Rajkot, Marwadi Shares, was adding about 1,000 new customers every month. That is now up to 6,000 new customers a month, said Ketan Marwadi, its managing director.

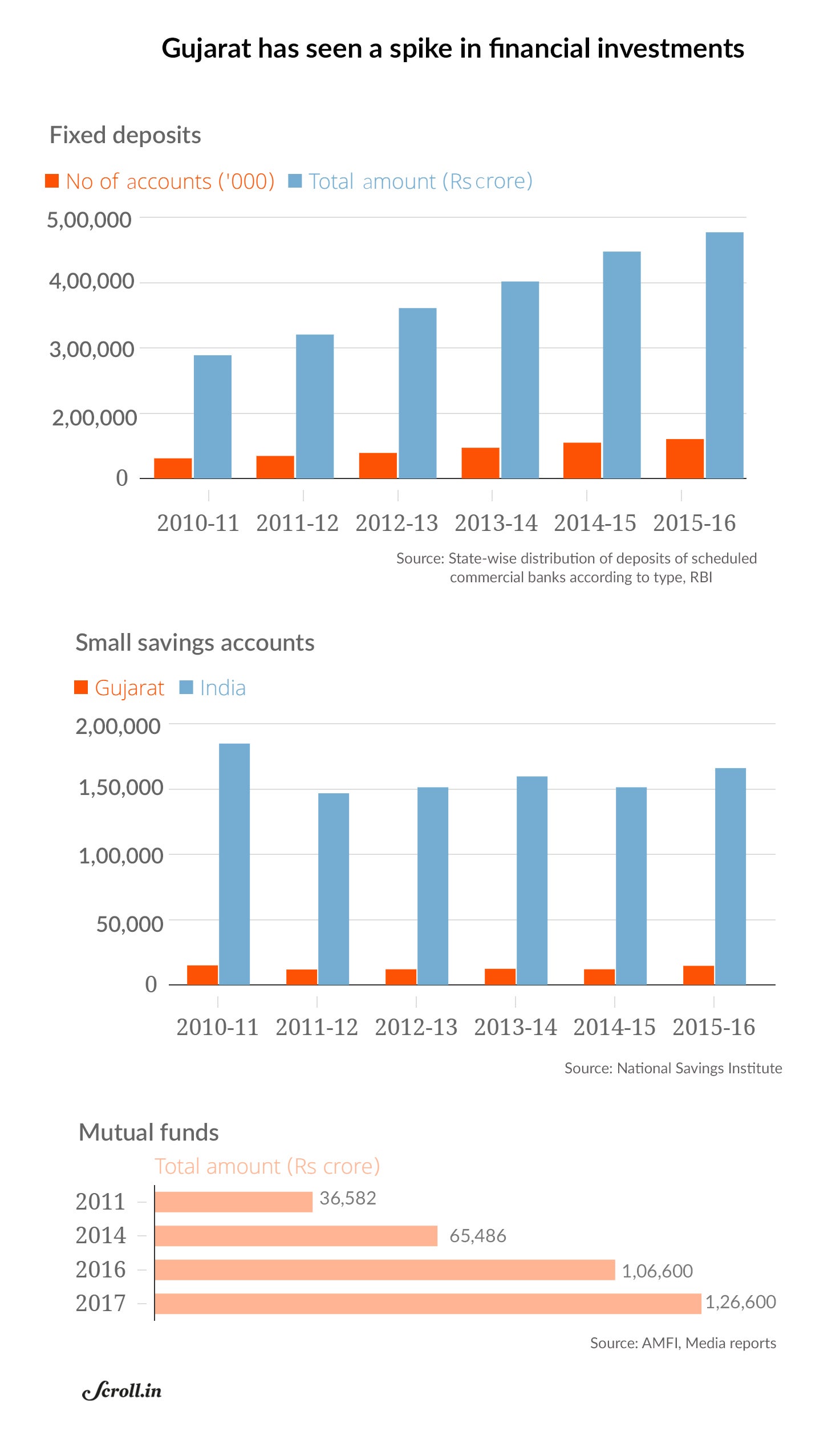

Data for the last five years shows the state’s people are investing more in fixed deposits, mutual funds, and small savings accounts.

Businessmen in the state say the two trends are related—an industrial slowdown is leading to a rise in financial investments.

A broader national trend

This mirrors what Scroll.in’s Ear To The Ground project has found in other states. In Punjab, Odisha, and Tamil Nadu as well, businessmen were putting their money into speculative schemes instead of factories.

In Punjab, businessmen diverted working capital loans for their sinking businesses to land purchases. In Odisha, earnings from the state’s iron ore boom were funnelled into gold, real estate, apartments, education, and chit funds. In Tamil Nadu, moneylending appeared to outperform more productive enterprises in terms of returns.

If this trend is widespread, it indicates that micro, small, and medium enterprises are not able to generate satisfactory returns.

A good starting point is to compare relative returns from investments in industrial activity and financial instruments. That said, calculating economic returns of micro, small and medium enterprises is not easy. Most data on the financial performance of India’s corporate sector focuses on the country’s top 500 companies.

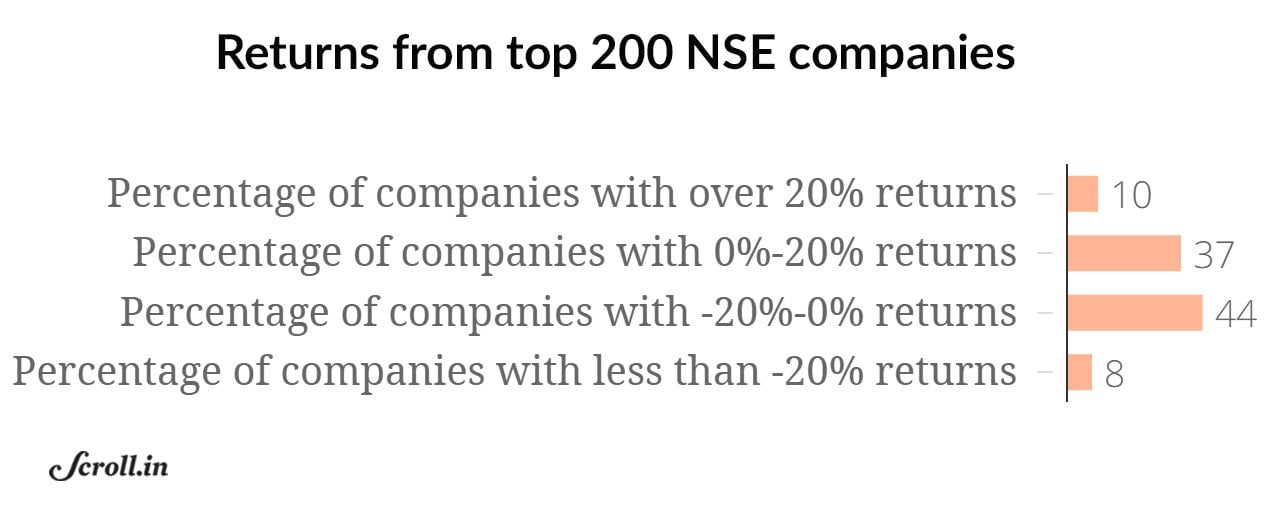

But even that data is a starting point. Between 2013 and 2017, returns have fallen even for larger companies. Sashank Vipparthi, a portfolio manager at an investment firm in Hyderabad called Impact Consulting, calculated the return on capital employed—a metric used to measure companies’ profitability—for the top 200 companies listed on the National Stock Exchange. He found that it had fallen from 28% to 14%. As the chart below shows, no more than 10% of these companies yielded returns above 20%. As many as 52% posted negative returns in this period.

What about micro, small, and medium enterprises? “My guess would be if large companies are doing badly, they must be doing worse,” said Vipparthi. That is because smaller companies are more vulnerable to market swings.

Why is business profitability falling? The fundamental problem, he said, is lack of growth in domestic demand. This has created an outcome where, according to S Ananth, a researcher based in Vijayawada who studies India’s financial markets, companies are sitting on unused capacity, margins are falling, and profits are under pressure.

The fallout? Even large companies, said Vipparthi, are investing in financial instruments. Investments in the stock market, directly and through mutual funds, are giving annual returns above 20%, he said. In contrast, industries are generating returns of about 11%, and debt instruments such as bonds and debentures are yielding around 6%-7%.

What is happening in Gujarat?

Much of this is playing out in Gujarat as well. When key industrial sectors such as textiles, metal products, automobiles, and chemicals suffer a slowdown, small enterprises supplying to them also struggle. A slowdown in demand is not the only factor weighing them down though. Take Surat. The textile cluster is under pressure from Chinese imports and the entry of larger companies, both of which are putting margins under pressure. This feeling of insecurity has been exacerbated by demonetisation and the GST, resulting in many units shutting down.

Dhirubhai Shah, managing director of Shahlon Industries, a company in real estate and yarn manufacture, has a dire prognosis for Surat. At this time, he said, “Surat has 700,000 looms operated by 10,000 companies. In five years, that will come down to 2,000 companies. We have 400-500 companies in processing. We will see similar consolidation there as well.” In other words, competitive advantage is moving towards a few larger units.

The outcome, said KK Kakhar, former head of economics department at Rajkot’s Saurashtra University, is a growing crisis of confidence among businessmen. As economic uncertainty increases, he said, businessmen are moving to financial speculation. “Financial capital is giving better returns than production investment,” he said.

Ananth sees parallels between the present situation and the one India experienced in 1993-97 when, as their businesses went into a slump, a generation of businessmen moved their savings into the stock market. “It keeps happening when people find margins wiped out and simply take money to speculation in the stocks or commodities,” he said. “I think we are seeing signs of this.”

What has changed is where this money is going.

Money talks

About 10 years ago, people in Gujarat had a range of investment vehicles to choose from—land, the stock market, bank savings, gold, day trading, moneylending, informal exchanges for commodities and stocks (known as dabba trading), and more. Some of these were used to park and grow black money. “Before demonetisation, 50%-60% of the people used to put their money into real estate,” agreed Marwadi. “That is also where do number ka paisa used to go.”

That range of investment options has shrunk. Land is not as attractive. In the urbanising belts around Rajkot, property rates have been stagnant for the last two years (more on this in a subsequent report). At the same time, as Marwadi said, demonetisation has made people more wary of investing in land, property, and gold. Because of crackdowns by the Securities and Exchange Board of India, money flows into dabba trading have slowed as well. From talking to people in the state, it seems the only informal instrument that is still sizeably used is moneylending.

In the old days, Gujaratis used to invest in both formal and informal instruments in order to hedge risk. Now, most of the money seems to be going into financial instruments such as stocks and mutual funds. This rush into the stock market creates its own impetus by feeding into the markets’ bull rally, and attracting even more investment. This can get risky.

What happened in 1997 was a stock market bust, followed by one generation of investors posting losses and swearing off the markets for good. They had entered not as long term investors but as speculators. Which is what is happening again with a new generation of investors.

“They will want to make money at the end of their trades,” said a sociologist who did not want to be identified. “And all the bets are not going to pay out. And they do not have the bandwidth to lose money.”

MS Sriram, who teaches at IIM Bangalore’s Centre for Public Policy, cautioned: “If people are moving out of the primary sectors to the financial services sector, it is a cause for concern. Financial services come in only when there is enough production and economic activity.”

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].