An exhibition in London explores the rich history of India’s contributions to science

There’s perhaps no better time to celebrate India’s real contributions to science.

There’s perhaps no better time to celebrate India’s real contributions to science.

Over the past few months, superstitious beliefs and myths about India’s past have become increasingly pervasive, particularly promoted by local leaders. At the same time, funding for genuine research is drying up, and despite protests from the scientific community, things seem to only be getting worse.

But at the Science Museum in London, the emphasis is on what India has done right, going as far back as the Indus Valley Civilisation. As part of its Illuminating India exhibition to mark the country’s 70th year since Independence, the museum is highlighting Indian innovation with a collection of key objects from the past, including the Bakhshali manuscript, which was recently found to be the oldest record of the zero symbol, and Jagadish Chandra Bose’s oscillating plate phytograph, which was used for the scientist’s revolutionary research on the movement of plants.

Besides telling the stories of inspiring scientists and thinkers from the region, the exhibition also features several of India’s more recent innovations, from the Indian Space Research Organisation’s (ISRO) Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle to the affordable Micromax smartphone.

Here are some of the objects that will be on display:

Ancient weights

These weights date back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, which is belived to have existed at around the same time as Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia. Archaeologists believe that the weights were used to measure everything from food to precious gems. Together with the linear measures and masonry tools found at excavation sites in what is now Afghanistan, Pakistan, and north west India, they suggest that the people of this ancient civilisation had the mathematical tools and knowledge to build complex cities.

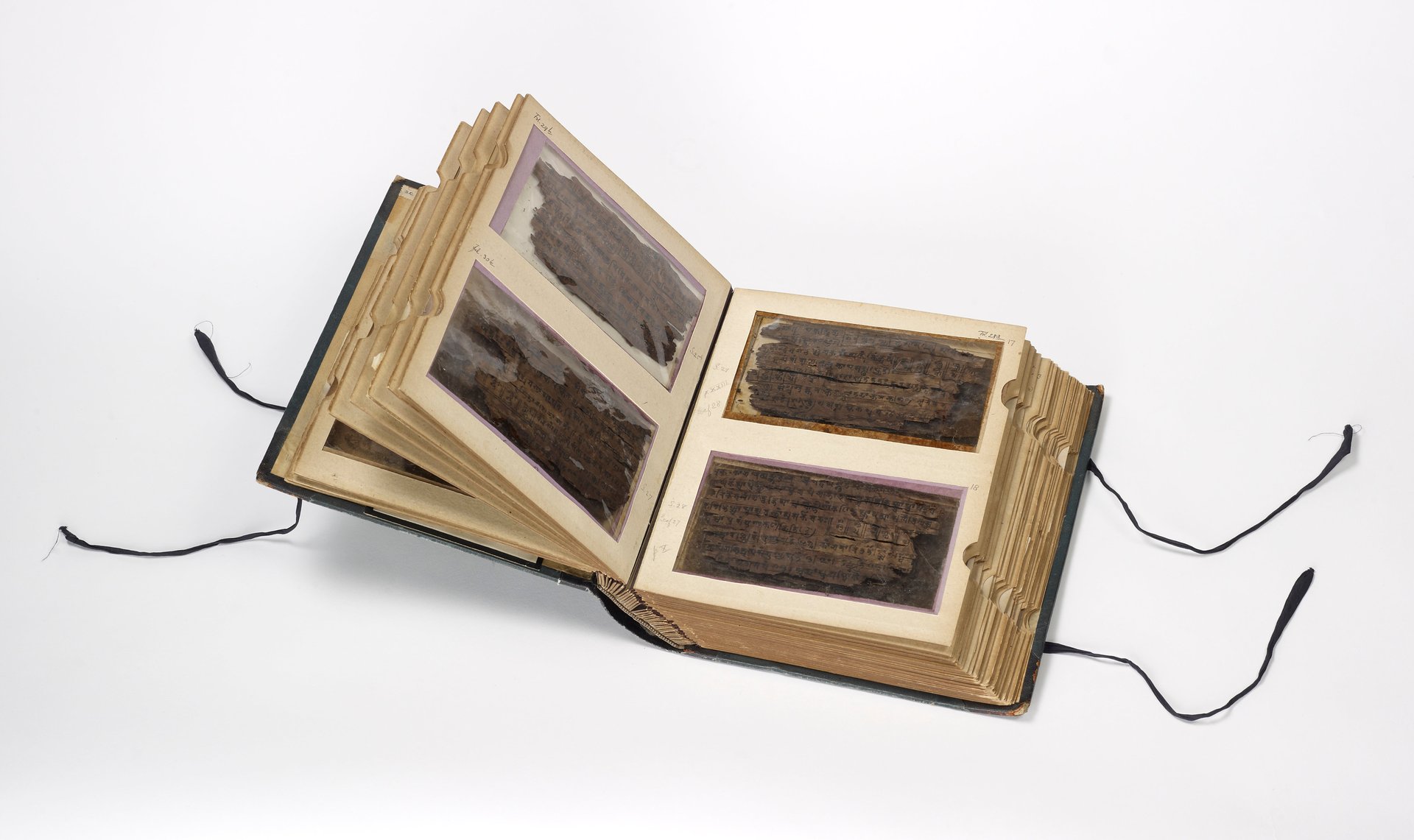

The Bakhshali manuscript

This ancient manuscript was found buried in a village called Bakhshali near Peshawar (now in Pakistan) in 1881. Consisting of 70 fragile leaves of birch bark, the Bakhshali manuscript contains hundreds of zeros denoted by dots, and has been housed at the University of Oxford’s Bodleian Libraries since 1902. In September 2017, it was revealed that the manuscript was much older than previously believed, indicating that ancient Indians had pioneered the revolutionary idea of using zero as a placeholder number as early as the 3rd or 4th century Common Era.

The Bhugola

Dating back to the 16th century, the Bhugola, or “Earth ball,” is a container made from brass that has a map of the world depicted on its outer surface. But this map combines two very different ideas of what the world is supposed to look like: one is the traditional Hindu idea that the universe is egg-shaped and divided across the middle by the flat disc of the Earth, while the other is the Ptolemaic idea of the Earth as a sphere, which came to India from Greece via the Islamic civilisation.

The oscillating plate phytograph

Born in 1858 in what is now part of Bangladesh, Jagadish Chandra Bose went on to become one of India’s most iconic scientists, pioneering research into radio and microwave optics, besides investigating the movement of plants, and even dabbling in a bit of science fiction writing.

Bose created the oscillating plate phytograph to study the effects of environmental factors on plants, and made groundbreaking contributions to the understanding of tropism—the movement of a plant towards or away from stimuli such as light, warmth, or gravity. His research into the responsiveness of organic and inorganic matter helped develop the field of biophysics.

Jaipur foot prosthesis

The Jaipur foot prosthesis is a prosthetic limb developed in 1968 by the craftsman Ram Chander Sharma and orthopaedic surgeon Dr PK Sethi. Made with a combination of rubber, plastic, and wood, the prosthesis was designed to be both cost-effective and more flexible than traditional Western versions that were made with metal or carbon fibre.

Since 1975, the charity Bhagwan Mahaveer Viklang Sahayata Samiti has been manufacturing and distributing the prosthesis to people in need around the world. Its design has been refined over the years, notably in 2009 with help from Stanford University.

ISRO’S Polar satelite launch vehicle

Developed by ISRO in the early 1990s, the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) is the most iconic Indian rocket, a mark of the country’s rapidly advancing but still frugal space programme. Though its very first mission in 1993 wasn’t a success, the PSLV has since gone on to successfully launch a number of satellites for countries such as the US, UK, and Canada, too. And earlier this year, the PSLV launched a record-breaking 104 satellites in a single effort.

The Micromax smartphone

Gurugram-based Micromax started out in 2000 by selling extremely affordable phones with features such as dual SIM capabilities and longer-lasting batteries. By pricing its products for as little as Rs900, the company provided innovative technology that would have otherwise been out of reach for a large segment of India’s rapdily growing mobile phone subscriber base. Over the years, it has roped in Hollywood stars such as Hugh Jackman to endore its products, and evolved into one of the country’s largest smartphone makers.

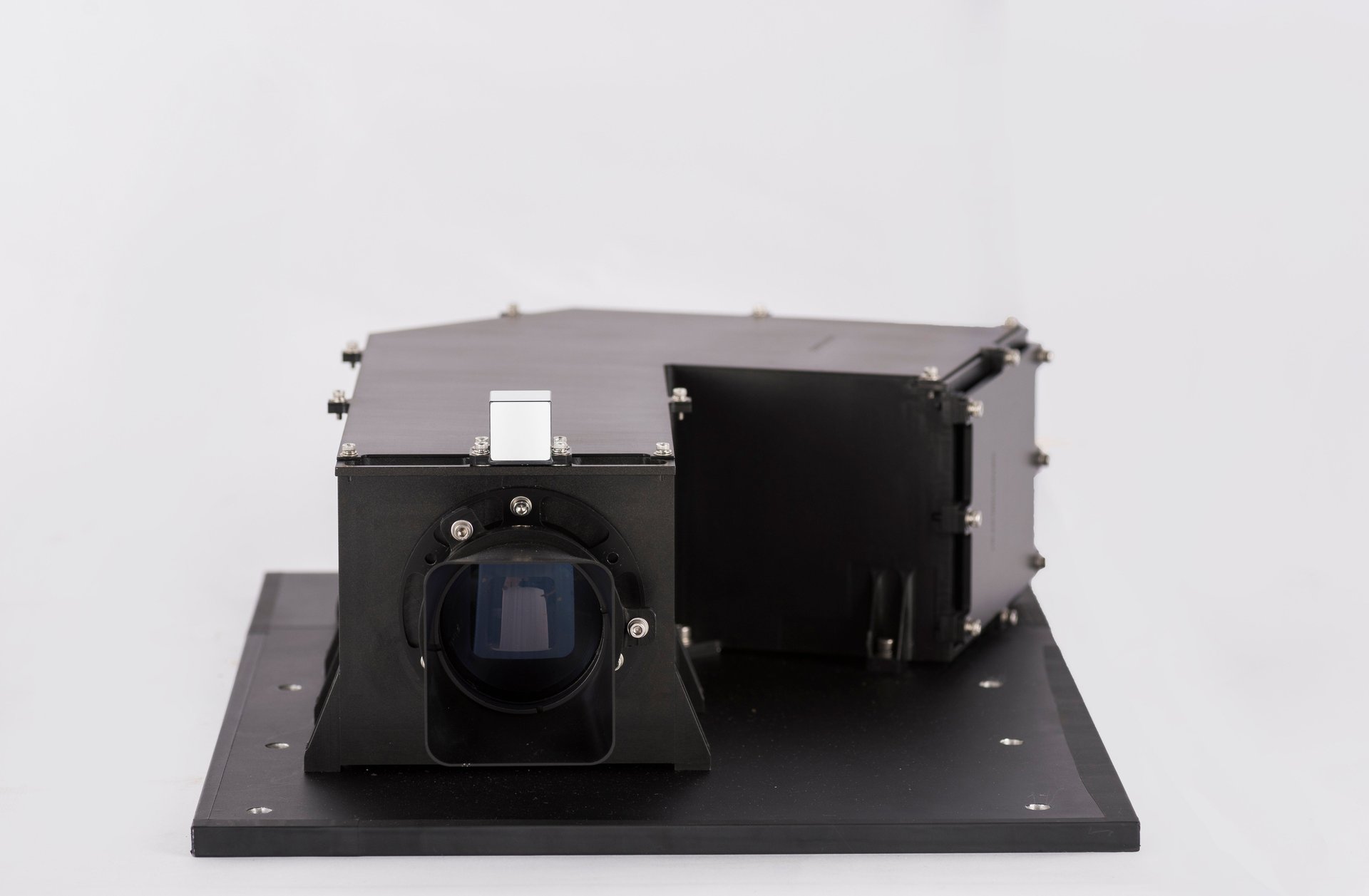

The Mars colour camera

In 2014, Indians celebrated the success of Mangalyaan, the Mars Orbiter Mission, which reached the red planet on its first attempt. At a cost of just $74 million, the entire mission came in cheaper than the 2013 Hollywood science fiction thriller Gravity.

One of the instruments used was the Mars Colour Camera, which took detailed colour images of the mountain ranges, fracture systems, and dust storms on the planet and its moons. These images were used to compile India’s first Mars Atlas.