Once a month, I am my barber’s muse and also his work of art

There’s one expression that most Indian males get to hear virtually every month. It is most likely to be thrown at them first by their mothers. As they grow up (of course they do!), the skill is honed by their girlfriends, who master it by the time they turn wives. And the cycle continues.

There’s one expression that most Indian males get to hear virtually every month. It is most likely to be thrown at them first by their mothers. As they grow up (of course they do!), the skill is honed by their girlfriends, who master it by the time they turn wives. And the cycle continues.

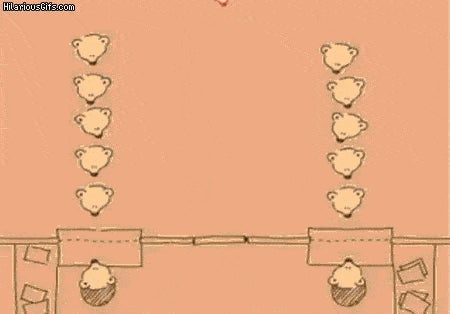

The term is jungle—jangal in Hindustani, kaadu in most south Indian languages, bana in Oriya—and so on, and refers to the degenerate state of one’s crown, overgrown with hair.

So, for instance, we have, “Munda ta bana helani. Barik pakhaku ja!” in Oriya, which roughly means: “It’s a jungle there on the head. Go to the barber.” Or like a former colleague’s mother would often say in Assamese: Jongholi bhoot tur dore lagise (You look like a jungle ghost!). The grave implication is obvious.

With the kind of unruly hair I’m blessed with, it usually doesn’t take long for this to come by every month—earlier from my mom, now from my kids’ mom.

So, having exhausted all the excuses, off I go to the friendly neighbourhood barber at “Classic Hairdressers.”

It’s not that getting a haircut is painful (perhaps it evokes a childhood trauma of the first time the scissors went snip-snip over my head, and I saw my body parts, even though just hair, drop all around me). It’s just that the hour or more spent at the typical Indian barber shop is plain boring for even a weekday, let alone a Sunday. Particularly if it is the first weekend of the month, which it almost always is. Because however early you reach the salon, the entire neighbourhood and the adjacent one are already there with a single-point agenda of keeping you waiting.

The wait could vary between around 20 minutes to over an hour, depending on when one chooses to visit.

Did you say, “Try another salon if you can’t wait”? Yeah? Well, this is what happens.

So there I sit, flipping through all the newspapers and their weekend supplements, and then the movie magazines. Some joints have radios blaring out Bollywood songs—and why is it always the atrocious 1990s hits? Even those places with a TV have an obsession for B-grade movies and their jarring music. While there’s always my phone to while my time away, it’s risky. Very often, Twitter and Facebook have cost me my turn.

But the wait does end ultimately, and I finally do get to the hot seat.

“Haircut please.”

“How do you want it?”

“Short.”

“Very short, or just medium short?”

“Very short on the sides and in the rear, medium otherwise.”

“Shave?”

“No. Just haircut.”

“Shall I use the machine?”

“Sure.”

Now the artist prepares. He’s obviously run out of fresh aprons, so he vigorously dusts a used one, swings it over my head, and ties a knot behind my neck. His canvas, my head, is ready. Out comes the hair-cropper, which he plugs into a power socket. And then… he takes a break.

A break? He didn’t begin, did he? Never mind. He takes a break anyway, to chat with his colleagues. The topic could vary between politics and movies to the breakfast from the canteen next door and his fantasies involving Donald Trump or Kim Jong-un’s mane.

Sorry mate, you’ve got just me for now. And I am waiting, waiting, bored, waiting, irritated, waiting…

He returns eventually, but the chattering continues. He positions my head, strategically tilting it to an acute angle of 60 degrees—who dares change that position set by the master?—and begins to slide the cropper through the thicket. A monologue is now directed at me.

“How do you suppose things will improve if this is how people behave?”

I am already lulled by the cropper’s rumble over my cerebellum. So I don’t notice, nor respond. There’s no stopping him though.

“At least in public they should remain honourable, hai ki nahi?” (That last bit in Hindustani is the leitmotif in every third sentence he rolls out. It means, “Is it not?” And my answer better be in the affirmative. Remember, his canvas = my head.)

I’m deeper into the hypnosis, so even less chance of a response. Noticing the irreverence, the maestro subtly hints his annoyance by pausing and taking the question to his colleagues again. The rumble on my head stopped, I wake up from my stupor and lift my head at him. His point made, the barber returns and picks up the conversation from where it ended a few moments ago. I simply say, “Haan (Yeah).”

“So how should anyone deal with such a human being?”

“Haan.”

The maestro tilts the canvas to the right.

“He has a family, too, doesn’t he?”

“Haan.”

“So why would he be so insolent towards others?”

“Haan.”

The canvas is now tilted left.

By now, my head is already feeling lighter from the cropping and the buzz is really nice.

Intermittently, there is this one inescapable problem: the falling hair. Not the ones that land on the apron; the daze dilutes the morbidity of watching those go. It’s the ones that land on the face that stoke irrepressible irritation. They behave like those visiting distant relatives who, just before leaving for good, present you with that one last annoying moment. No itch in life is as frustrating as the one sparked by lumps of ones own hair settling on parts of one’s face—cheek, nose, upper lip. Hands under the apron, one can only seek the maestro’s help. And he promptly waves the big brush across the face to my relief.

My eyelids are heavy again. And he continues:

“Not everybody is rich you know?”

“Haan.”

“Are you sure you’re not getting a shave?”

“Haan.“

“Ok. Your wish.”

“Wait, what?”

“Gotcha!” says his posture as he stands there satisfied at his latest creation.

Reverie broken, I look into the mirror before me. Neat. He brings up another mirror from behind to show me the rear side. In one last act, he showers the big brush with some talcum powder and sweeps along the edges of the decimated jungle. That feels nice.

I give the mirror one last look and also glance at the wall with the many posters of Bollywood hunks and their glorious “hairstyles.” A smart summer cut will do for me.

The Rs50 paid for the service (shaving costs another Rs35, and a mild body massage Rs50 more), I make a dash, feeling far lighter and more at ease now than when it began. And till the jungle regenerates, my head will remain his work of art.

P.S.:

- On average, Classic Hairdressers makes around Rs600 a day in profit, tending to around 35 patrons on a weekday, says Sanjeev Sharma, its owner. On weekends, the number of patrons could go up to 50 or even 100 if it is the first one of the month, Sharma said.

- Indian women mostly don’t get to experience all this—though some do—primarily because of the country’s penchant for their long tresses. Also, by the time they are old enough to want to style their hair, they prefer the neighbourhood “beauty parlours” over “hairdressing salons.”

We welcome your comments at [email protected].