What is it like to be a child trafficking victim in India? An online game will put you in her shoes

Every year, thousands of young Indians are torn away from their families and forced into slavery—and hardly anyone stops to think of their struggles.

Every year, thousands of young Indians are torn away from their families and forced into slavery—and hardly anyone stops to think of their struggles.

Despite laws against it, the National Crime Records Bureau’s (NCRB) latest data shows 6,877 human trafficking-related cases recorded in 2015, up 25% from the year earlier. A significant portion of the victims included girls under the age of 18 from poor families in states such as Assam, Bihar, and West Bengal. Many of them were sold into sexual slavery and endured years of exploitation with little hope of escape.

For long, the Nobel Prize-winning activist Kailash Satyarthi has worked to raise awareness about this issue. His foundation is now using a new platform to spread the message: (UN)TRAFFICKED, an online, choose-your-own adventure game that seeks to put users in the victims’ shoes.

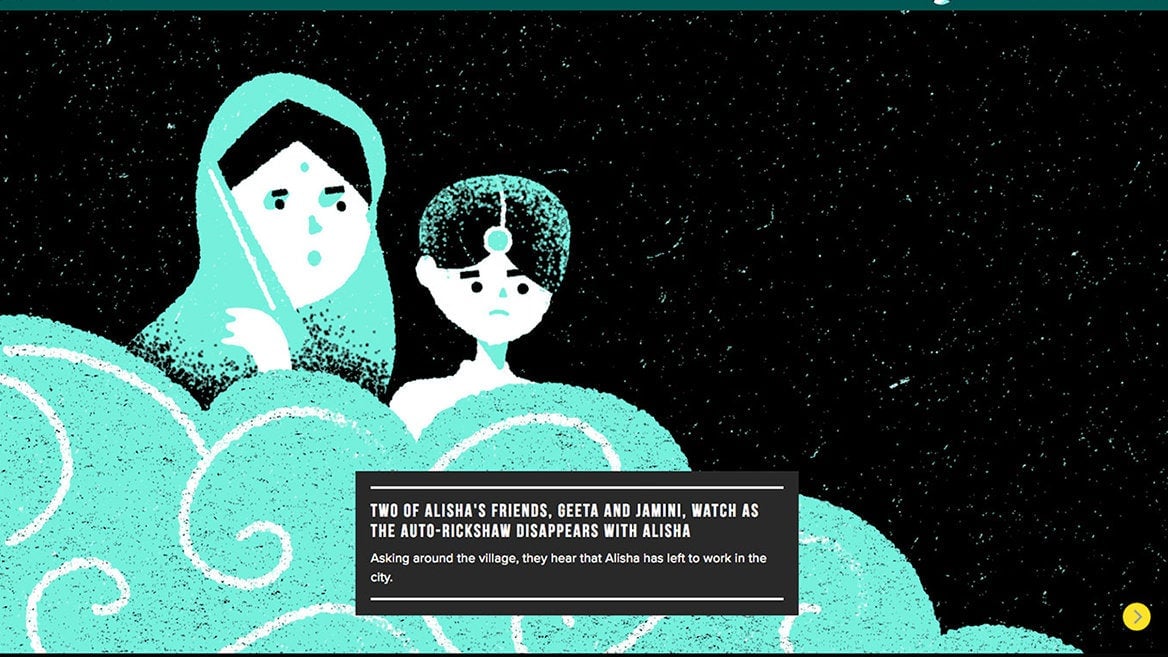

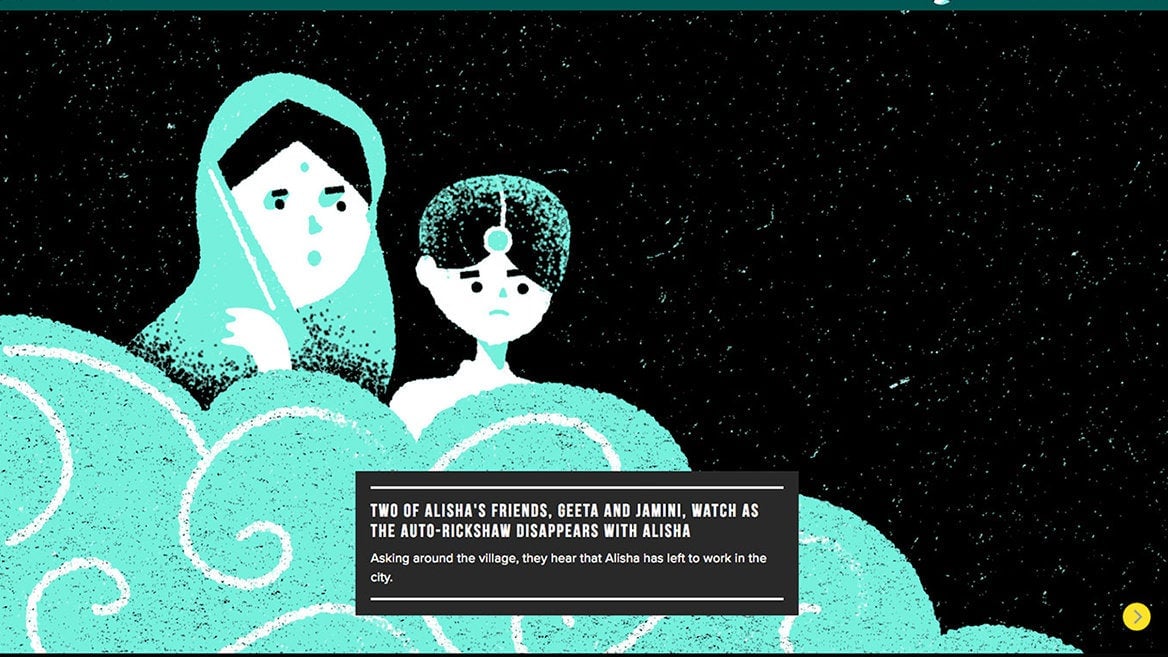

In the interactive story, users follow the journey of a 13-year-old girl from a poor family that decides to send her away with a stranger to find work in the city. As the story proceeds, users inhabit many other characters, from money-minded agents to the apathetic police, and get a glimpse of how other people’s decisions push the young girl into a life of misery.

“One of the main reasons children get trafficked is because so many of us are either willing to look the other way or are simply ignorant of the problem,” Aditi Mukherji, a spokesperson for Kailash Satyarthi Children’s Foundation, told Quartz in an email. ”We are hoping to reach out to people from all across the diverse spectrum of India, from rural parents to urban youth to law enforcement, because in our view the world will be safer for children only if all of us band together to make it so,” she added.

The project is available in both Hindi and English, making it accessible to more Indians. The foundation also has plans to release it in other regional languages. Since its soft launch on Oct. 14, Mukherji said, the game has been played over 110,000 times, mostly by Indians.

This project comes after Satyarthi kicked off a 36-day, cross-country Bharat Yatra in September, marching with numerous victims, students, and other supporters to raise awareness about the sexual abuse and exploitation of children in India.

But solving the problem isn’t going to be easy.

“The first thing we need is stricter laws with regards to child trafficking and for cases of trafficking to be adjudicated swiftly and effectively,” Mukherji said.

Activists have for long criticised India’s existing laws for being an inadequate “patchwork,” and called for more comprehensive legislature. The government’s 2016 proposal for a new anti-trafficking bill also met with disapproval because of its unclear definition of the very term and a lack of a clear and effective strategy to address the problem.

Moreover, courts have a terrible track record, too. In 2015, for instance, trials were completed for only 384 out of the 5,003 child trafficking cases. Only 55 of them ended in conviction, resulting in a conviction rate of just 14.3%, according to the NCRB (pdf).

Nevertheless, the foundation says its interactive project is a useful platform to get more Indians talking about the problem, which might eventually lead to change.

“We chose this particular platform because of the immediacy it offers and the participation it invites,” Mukherji said. “The child’s subsequent suffering is a powerful way to inform people of their everyday choices, and how they could affect a section of people they might not have given a lot of thought to before.”