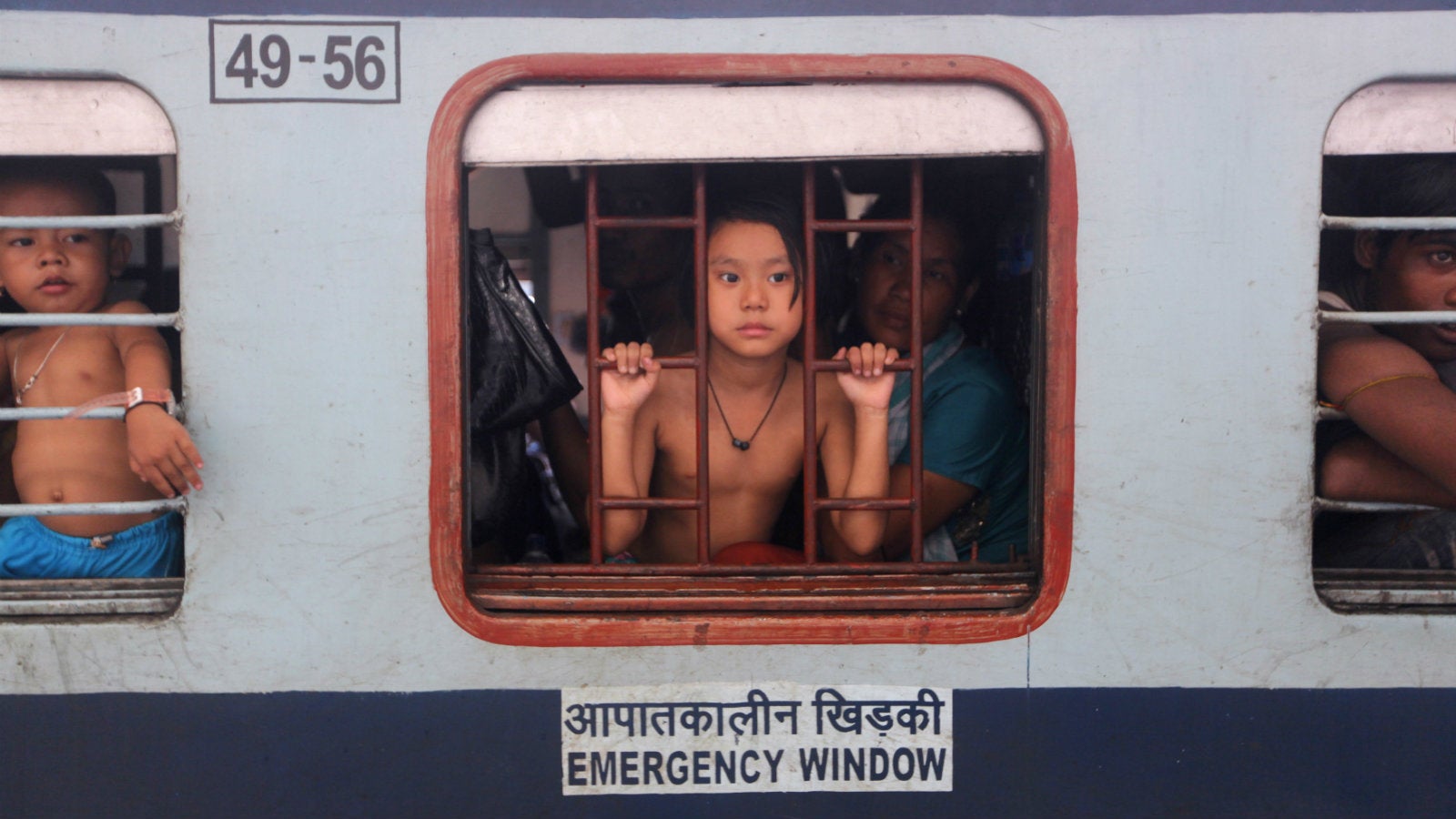

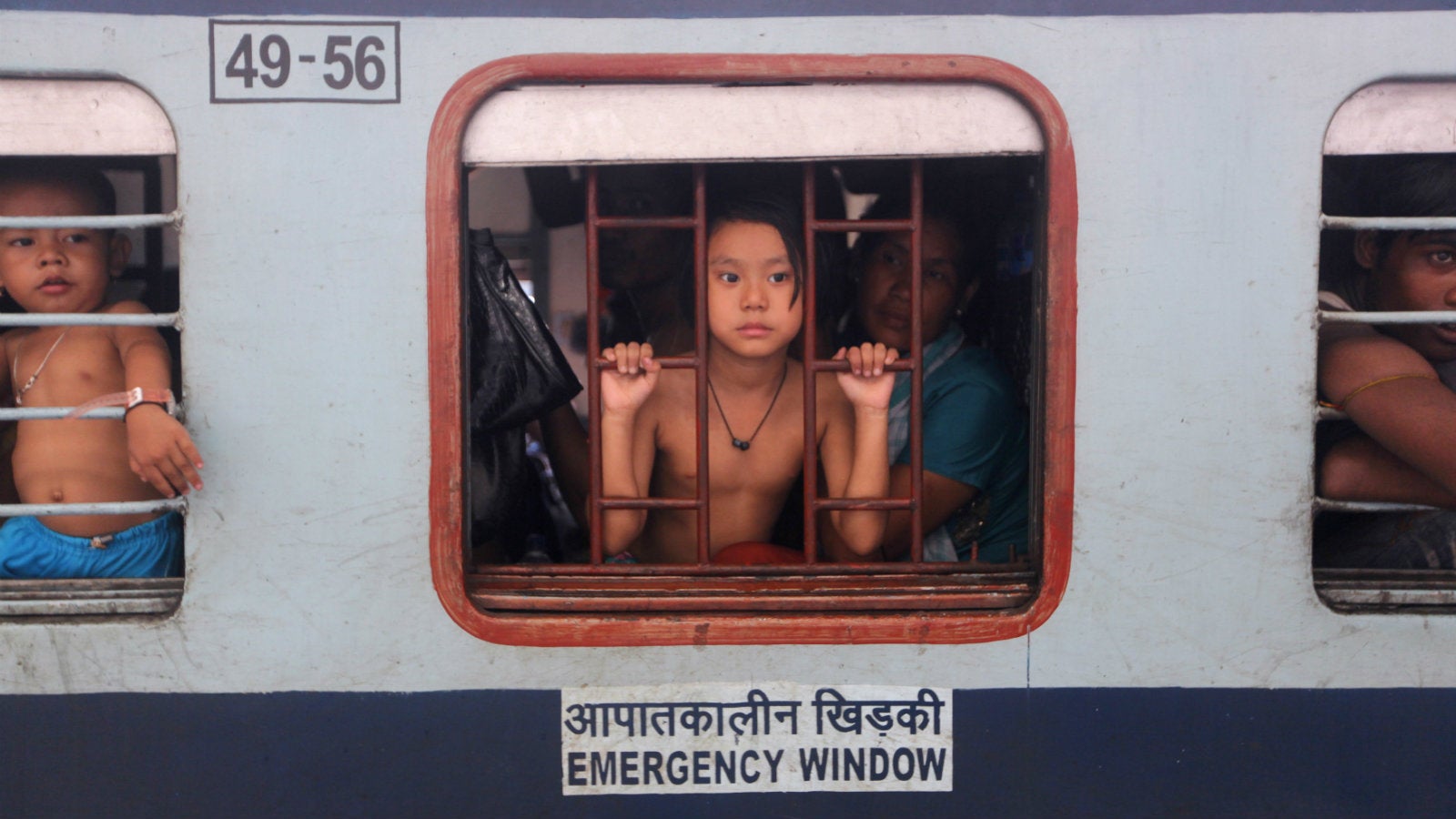

Why the young from India’s northeast are building bridges with the country’s big cities

In February 2013, a young man from Arunachal Pradesh entered a shop in Lajpat Nagar, New Delhi, wanting help in locating a relative’s address in the neighbourhood.

In February 2013, a young man from Arunachal Pradesh entered a shop in Lajpat Nagar, New Delhi, wanting help in locating a relative’s address in the neighbourhood.

What happened inside and outside that shop resulted in his death and forced many Indians to look at and rethink ideas and issues of racial discrimination and viciousness towards those from the Northeast and towards people who just happen to “look different.”

Eighteen-year-old Nido Taniam walked into Rajasthan Paneer Bhandar to ask for directions. The shopkeeper made fun of his hair, which was streaked blonde. Furious at the insult, Taniam smashed a glass counter in the store. Such insults were not new for those from the northeast who, despite supreme court edicts, government diktats and assertions by human rights groups were still often treated as second-class citizens, snubbed as “Chinkies” because of their facial structure and regarded as promiscuous because they mingled easily with each other. They complained of often being overcharged for apartment rents since there appeared to be a general sense that they came from wealthy families and could afford to pay steep rents.

In Nido’s case, angered by the youth’s reaction, the shopkeeper, his assistants and others in the store attacked him with their fists; varying accounts say that there were between three to seven men in the group.

This did not happen in the darkness of night but in broad daylight.

[…]

Nido died of excessive internal bleeding the next day. A relative of the youth said: “This is surely about racism. Everybody in Delhi discriminates against us based on our looks. We are living in India, but we don’t know whether we are actually living in India or not.”

[…]

Nido’s was not a solitary incident. There was a spate of events before and after his death. The challenges of discrimination do not appear to have been curbed but there appears to be both greater awareness, especially in the media, and a deeper determination among young people from the region who seek to affirm their rights and dignity as Indians.

In addition, a number of academic institutions and research groups have conducted studies on the ugly face of discrimination. What one of them, developed by the C-NES (Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research) at Jamia Millia Islamia, discovered was the determination of younger people to keep coming to the metros in search of better prospects in terms of jobs, opportunities, education and incomes. A new generation of younger people from the northeast was engaging with India and Indians, not as fighters against Delhi’s Raj but as equals seeking acceptance of these rights and entitlements. Perhaps it is here that the core conditions of the region have changed—that a generation of young Indians from this area, exhausted by conflict and bloodshed, by ill will and stress, now seek to carve a new way for themselves based on the laws and systems of “mainland” India. This is a remarkable change from an earlier time when their forebears, perhaps even their parents, were involved in political and armed fights for independence or autonomy against India.

It is a decision that is not mandated by the power of the gun or by the force of sheer numbers but by a growing realisation that the rest of India is moving ahead, even what was once known as BIMARU (Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, and Uttar Pradesh) states such as Bihar, and their lands and communities which had fallen way behind because of conflicts and poor governance, internal feuds, vast corruption and external interventions. Health and education indices have fallen as have incomes. The composite state of Assam was once the fourth from the top in terms of GDP at the time of Independence. Today, it is ranked below the group of BIMARU states while other states such as Tamil Nadu, Rajasthan, Maharashtra, and even Orissa (Odisha) have forged far ahead.

The Jamia study stressed this point. One of its key findings was that a striking 80% of the women who were interviewed said that although they had faced verbal and physical discrimination, they would still encourage their relatives and friends to migrate to a metro like New Delhi to scour for opportunities and set new goals. Hope or even the chance to hope is in itself a major driver not just of change but of out-migration.

[…]

Way back in 1996, writing about the deficits faced by the northeast, the Shukla Commission, which was set up by the then prime minister HD Deve Gowda to look at the challenges before the region, made some trenchant comments. Couched in the inimitable style of the veteran editor BG Verghese, it declared: “The northeast tends to be seen as a distant outpost, some kind of land’s end. Yet it was until recently a crossroads and a bridge to southeast and east Asia, with its great rivers ending in ocean terminals at Calcutta and Chittagong.”

The report’s introduction defined the core challenges: ‘There are four deficits that confront the northeast, a basic needs deficit; an infrastructural deficit; a resource deficit; and, most important, a two-way deficit of understanding with the rest of the country which compounds the others.” It said that while the region’s exclusive dependency on the centre for development funding was hurting it, what was needed was ‘a more rapid pace of growth (which) would generate larger internal resources. This could perhaps be enlarged through the additionality of private investment, Indian and foreign, within a well-defined framework.”

Noting that the area was a latecomer to development, it underlined that “the northeast must be enabled to grow at its own pace and in accordance with its own genius. It cannot be treated merely as a resource region, market dump and transit yard.”

It pulled no punches:

There is strong resentment over what is seen as an earlier phase of ‘colonial exploitation’ in which its wealth was extracted for others’ enrichment. Such a path of development is not advocated. On the contrary, the people of the northeast must feel that they are equal partners in a process of culturally friendly, equitable and sustainable development. This must be the thrust. Yet delay would be denial.

Excerpted from Sanjoy Hazarika’s book Strangers No More with permission from Aleph Book Company. We welcome your comments at [email protected].