India’s deep class divides extend to how its youth use the internet

Indian youth can’t escape the tough reality of their lives, even on the internet.

Indian youth can’t escape the tough reality of their lives, even on the internet.

Reliance Jio’s ultra-cheap data rates and the flood of affordable smartphones may be bringing more and more young Indians online every day. But it is hardly a level playing field—as is reflected in the usage patterns.

After all, the top 1% of the country’s population controls over 20% of its total wealth, and income inequality is said to be at its highest level since 1922. And this affects the way Indians access and use the internet across the board.

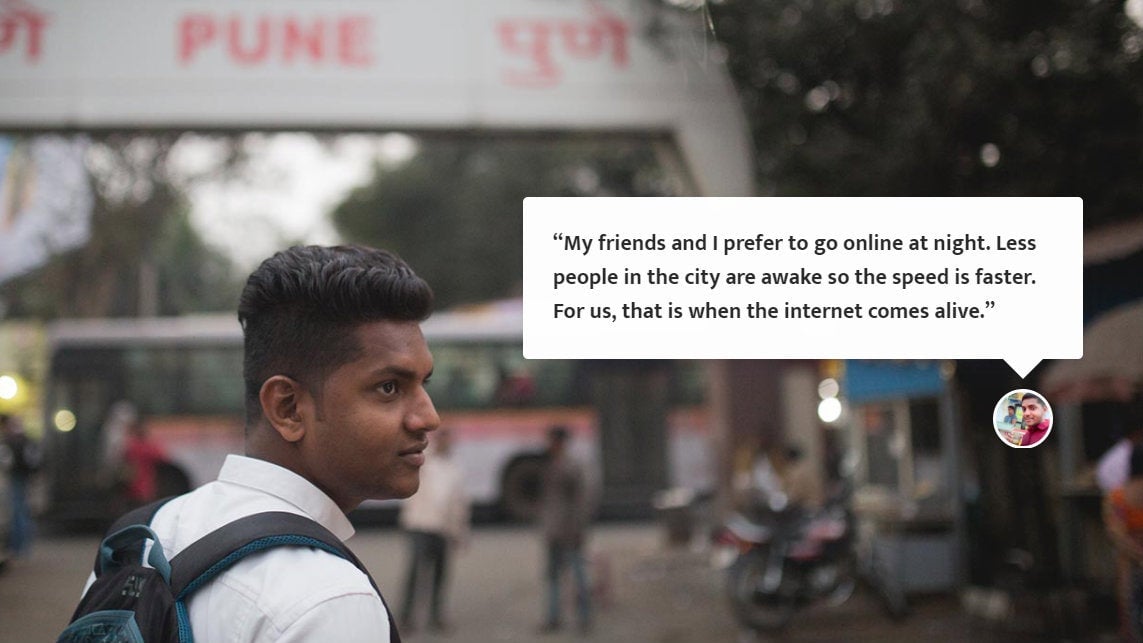

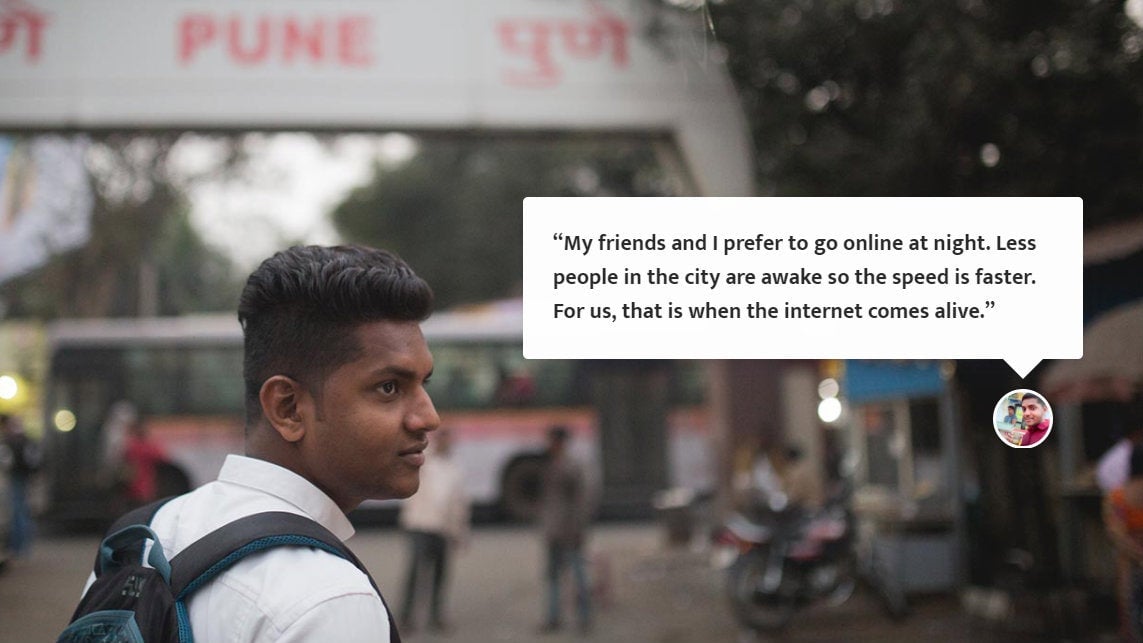

While surveys have shown that watching mobile videos (and porn) are popular pursuits, they haven’t really captured the nuanced and diverse reality of going online in India, and how millions are making their own rules when it comes to things like selfies and social media. But a new interactive website is out to change this, using the example of lower middle-class college student in the IT hub of Pune, Maharashtra. Titled Life in a Metro, the site showcases a day in the life of an ordinary Indian who can’t always afford wifi-enabled cafes when the internet isn’t available.

The website was designed based on research conducted by Rahul Advani, a PhD student at King’s College London, who was curious about how the world’s largest youth population engages with the internet.

“I wanted to know if there is anything they’re doing on the internet that’s very different from how social media is used in other countries where there’s been a much longer history of Facebook and WhatsApp and things like that,” the 27-year-old researcher, who moved to Pune briefly for his research in 2016, told Quartz.

It turns out, there is.

After interviewing over 300 college students, he spent several months following around 10 of them, all with varying backgrounds. These included those from elite engineering colleges and those from institutes lower down the rung.

Advani found that lower-income urban Indians have developed their own ways of integrating the internet into their daily lives, and using it to engage with the people around them.

The story of Life in a Metro unfolds as a chat with a computer sciences student named Rohan (a pseudonym assigned by Advani), who, after classes, takes viewers through a day in his life, travelling through the city, seeking out friends using Facebook, and taking selfies drinking chai (tea) or on his bike. In the process, we learn how millions like him have adapted to the limitations of slow speeds and poor access, devising ways to navigate the internet that are very different from those used by their counterparts abroad.

“One of the things I found very interesting was that social media (use), especially among lower middle-class youth in Pune…they were using it very much to facilitate the way in which they already interacted with each other,” Advani explained.

He cited the phenomenon of social media aggravating isolation and loneliness in countries such as the US and the UK, which, his research suggested, wasn’t necessarily the case for many young Indians. For instance, students used Facebook to frequently check-in at locations across the city. This, he said, was a way for them to see if any of their friends were nearby, making it easier to meet up in person.

He also found young Indians effectively rewriting the rules on social media.

The best example of this is the idea of tagging people on Facebook. Unlike in other parts of the world where the norm is to tag people in a particular picture, Pune’s youth tagged up to 30 friends, almost none seen in the photograph. Doing so helped make sure photo appeared on everyone’s newsfeeds, guaranteeing that it would get more likes, which Advani said was particularly important for all the youth he interviewed.

But perhaps the most interesting difference was the way India’s stark, real-life class divides played out online.

“Often people talk of the internet as this kind of place where everyone becomes equal and who you are offline doesn’t really matter…But what I felt in Pune was that that was not at all the case,” Advani said. “If anything, the internet, kind of, highlighted offline inequality.”

Rohan’s story reveals how much low-income Indians rely on their friends’ hotspots and the internet at their colleges. This is because they can’t always afford to frequent places like Cafe Coffee Day and Starbucks, where upper-middle-class youth can use wifi hotspots while sipping on a Rs100 cuppa.

Similarly, Advani found big differences in the way students from various social classes took selfies. The moneyed primarily chose fancy cafes and similar joints, like people in more developed countries. The poorer ones made the best out of the outdoors, usually blurring the background and adding emojis, filters, and other effects often viewed as tacky by the privileged. This selfie strategy is just another way for lower-income Indians to carve out their own space online, Advani says.

“It’s their way of showing that they can also confidently enter the internet, that they are also legitimate participants in this new digital India,” he explained.

Life in a Metro introduces viewers to the realities of internet use as lived by millions of Indians—and not just in Pune. However, there is one side of the story that is missing: women.

Understandably, in conservative India, female students weren’t keen on being followed by a male researcher for long hours. But the country’s internet also has a big gender problem, with just 29% of the users being female. The realities of their experiences, and what holds them them back from making the internet their own, is definitely something worth exploring.