India’s street magic once captivated the world, including Houdini himself

In 1893, years before he made his name as a legendary escapologist, a 19-year-old Harry Houdini sought to entertain visitors at the Chicago World Fair. So he darkened his face with makeup, put on a white robe, and posed as a “Hindu fakir.”

In 1893, years before he made his name as a legendary escapologist, a 19-year-old Harry Houdini sought to entertain visitors at the Chicago World Fair. So he darkened his face with makeup, put on a white robe, and posed as a “Hindu fakir.”

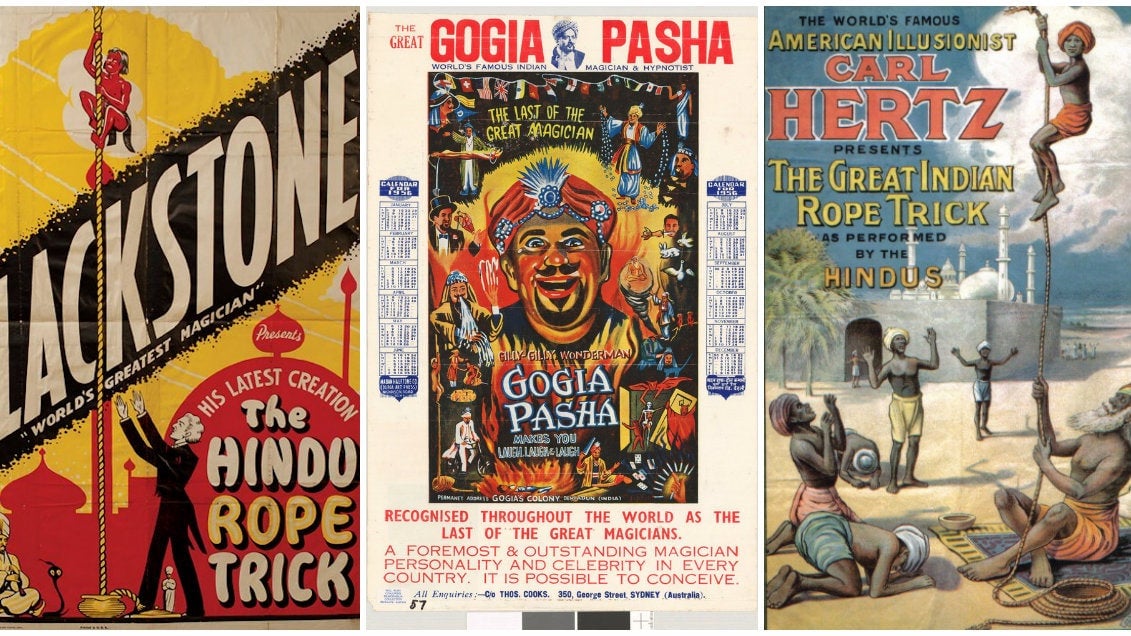

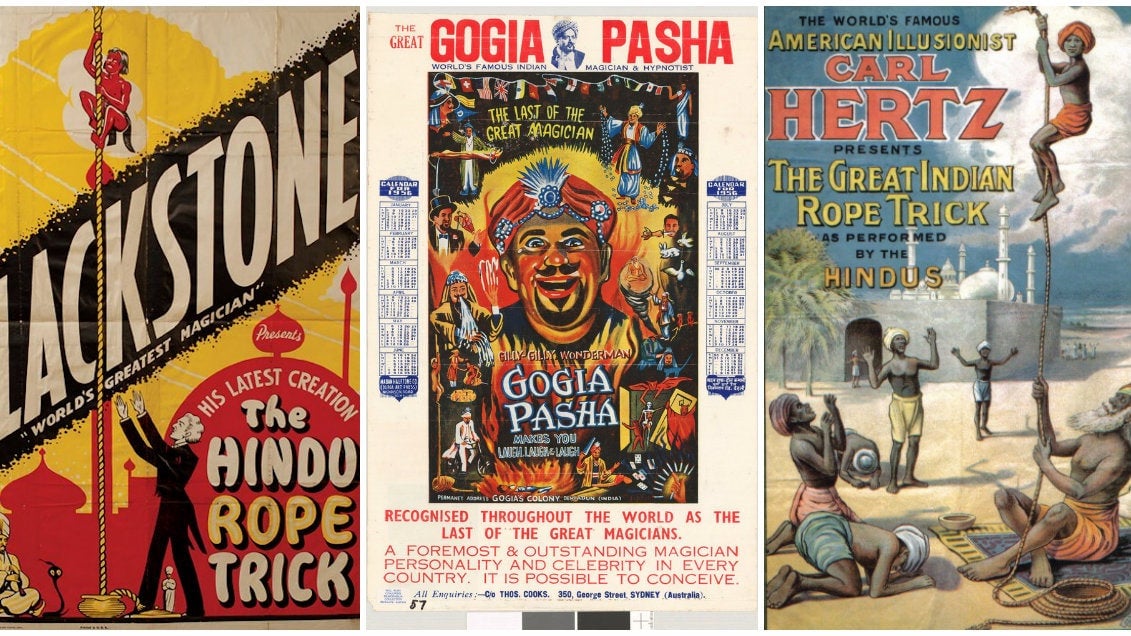

Houdini was capitalising on the growing fascination with the mysticism and magic of India which had sparked what one commentator described as a “fakir invasion” in the West. Indeed, he was following in the footsteps of many Western magicians who gave themselves titles like “The Fakir of Shimla” and “Fakir of Jeypoor.” These artistes dressed up in outlandish outfits, muddled together tricks from across the world, and passed them all off as Indian.

“…Science was able to explain everything, yet the East held out the promise that there were things out there that might not be explicable, that there might be a place where real magic existed. So Western magicians were very keen to exploit this belief,” said John Zubrzycki, the Australian author of the new book, Jadoowallahs, Jugglers and Jinns.

In the book, Zubrzycki traces the rich social, cultural, and political history of the art of magic in India. He explores its close connection with spiritualism and the changing roles of the country’s traditional nomadic street magicians, jugglers, and acrobats, once ubiquitous in Indian cities.

The author first visited India in the late 1970s and witnessed his first Indian street magic performance in West Bengal’s Alipurduar district: An old man and a young boy performed the classic basket trick—a child enters a small cane basket and appears to be stabbed repeatedly, only to re-emerge miraculously unhurt.

It wasn’t until decades later, when Zubrzycki was working on his second book about a diamond trader in Shimla who dabbled in magic tricks, that he thought of tracing the history of the art in India.

Zubrzycki has spent the past three years hunting down hard-to-find journals of Indian magic and meeting local magicians to hear about their lives and pore over their personal artefacts. His research took him from archives in Delhi, Mumbai, and Kolkata to London, Cambridge, New York, and Washington DC, where the Library of Congress hosts Houdini’s vast collection of books on spiritualism, magic, and witchcraft, which include many references to India.

He found that the enduring idea of India as a mystical place has its roots in the 6th century BC when historians, geographers, missionaries, pilgrims, and royal chroniclers began presenting the region as “a land of strange beasts and fantastical races, ascetics and saints, soothsayers and snake charmers, wonder-workers and necromancers.”

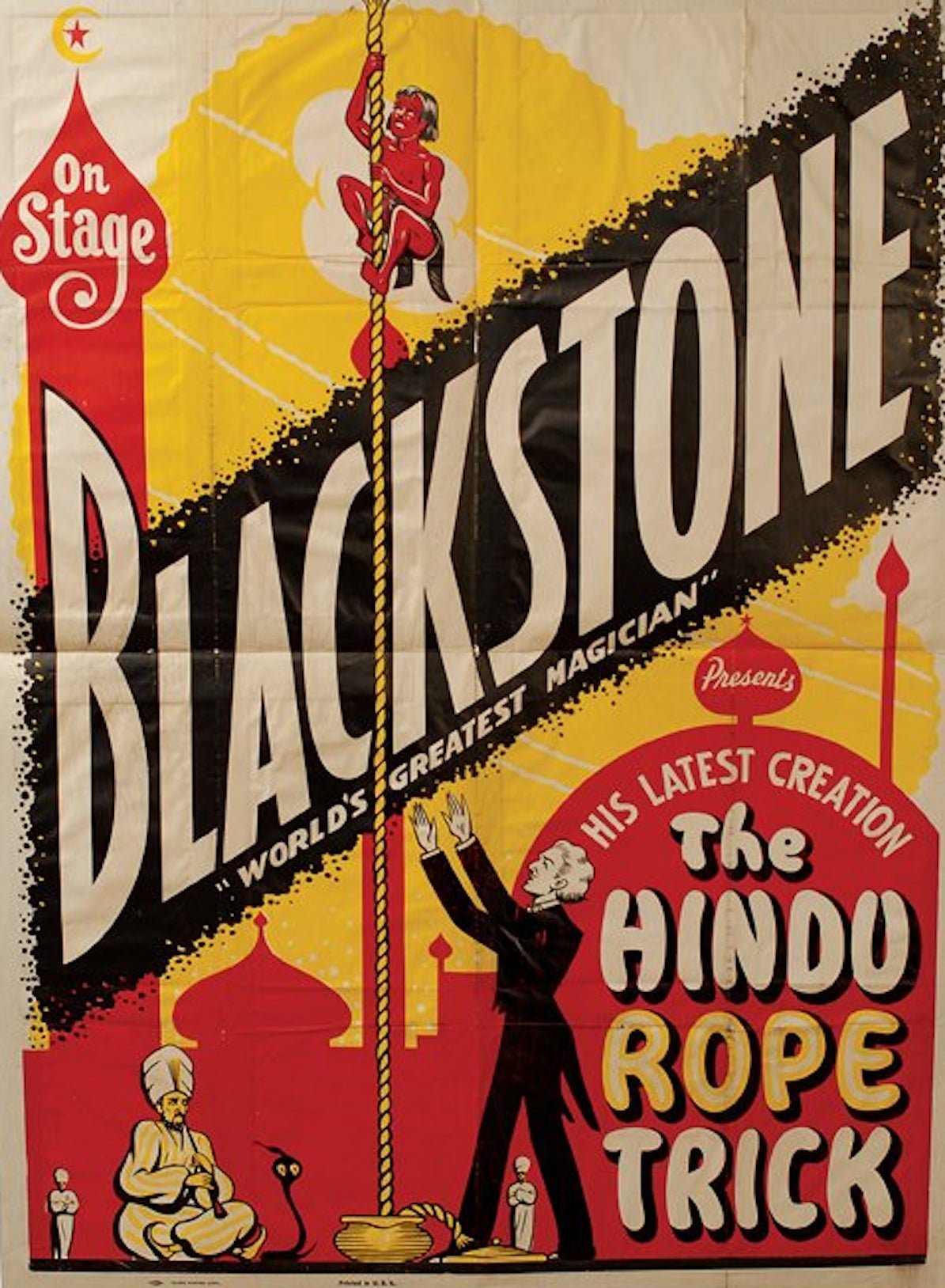

While such accounts were often highly exaggerated, over the years, Indian street performers did develop a mind-boggling repertoire of illusions. Feats such as the “Hindu Rope trick”—a piece of rope appearing to stay erect of its own accord, and a little child climbing it only to disappear above—shocked onlookers. This one trick itself would capture the West’s imagination so strongly that many spent time and resources trying to debunk or explain it.

Zubrzycki’s book is filled with colourful characters and anecdotes on Indian magic performers who began to travel west in the early 19th century. One of the most notable examples Zubrzycki cites is Madras-born Rama Samee, the once famous but now forgotten juggler and magician. Another chapter features Kuda Bux, a Kashmiri who performed as “The Man With the X-Ray Eyes”—he could reportedly read even with several layers of bandages, tape, cotton wool, and heavy cloth covering his eyes. Bux claimed he could see through his nostrils.

For the author, Indian magic wasn’t only about East versus West, with the two schools vying for global prominence, but also East meets West. After all, Indian street magic influenced Western magic, and vice versa. He found that just as Western magicians were lifting traditional Indian tricks, a new generation of middle-class Indian magicians were doing the same in the opposite direction, thanks to the spread of guidebooks, journals, and new magic societies.

“What really got me interested in the story was realising that around the turn of the century…late 1800s, early 1900s…you suddenly had these Indian magicians who were doing Western-style magic, dressing up in top hats and tails, and going to Europe and England and America and performing there,” he told Quartz. “And (over there) being surrounded by all these Westerners who were wearing turbans and sherwanis and pretending to be Indian and doing Indian-style tricks!”

This transition marked a big change from the old days when magic was primarily performed on India’s streets by the poor, marginalised communities without any bells and whistles—they had no stages or elaborate costumes, just a handful of props and enough charisma to draw a crowd.

Now the onset of the 21st century has definitively changed Indian lifestyles, making it harder for such artistes to earn a living.

“Once street magicians could start performing in a village square and people would marvel at what they were doing. These days, when people have access to television and the internet, those tricks start to look a bit dated and not as spectacular as they once were,” Zubrzycki said.

The implementation of laws against beggary have also made it difficult for magicians to perform on the streets as before, and harassment from the authorities is a persistent problem. Last year, the Kathputli Colony in Delhi, home to puppeteers, acrobats, musicians, and dancers, was razed to the ground for a redevelopment project, leaving many of its residents with nowhere to go.

Given the centuries of history and quirky characters, the dwindling legacy of Indian magic and street performance seems like an especially unfortunate end to an amazing story.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].