India’s first data protection bill is riddled with problems

India’s move to provide its citizens with comprehensive data protection rights may need a few rounds of relook before it can be considered effective.

India’s move to provide its citizens with comprehensive data protection rights may need a few rounds of relook before it can be considered effective.

On Friday (July 27), the justice BN Srikrishna committee submitted a draft Personal Data Protection bill, 2018 (pdf) to the Narendra Modi government. This bill will form the framework for India’s data protection laws, prescribing how organisations should collect, process, and store citizens’ data.

Once introduced in parliament, it will be subject to further review before becoming a law. The panel is already facing criticism for being too lenient and lacking in clarity on key issues.

“(The bill) is not without loopholes—in particular, the requirement to store a copy of all personal data within India, creating broad permissions for government use of data, and the independence of the regulator’s adjudicatory authority,” said Amba Kak, policy advisor for software company Mozilla in India.

Localising data

“Every data fiduciary (any entity processing personal data) shall ensure the storage, on a server or data centre located in India, of at least one serving copy of personal data to which this Act applies.”

— Chapter VIII (Transfer of Personal Data Outside India), The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018.

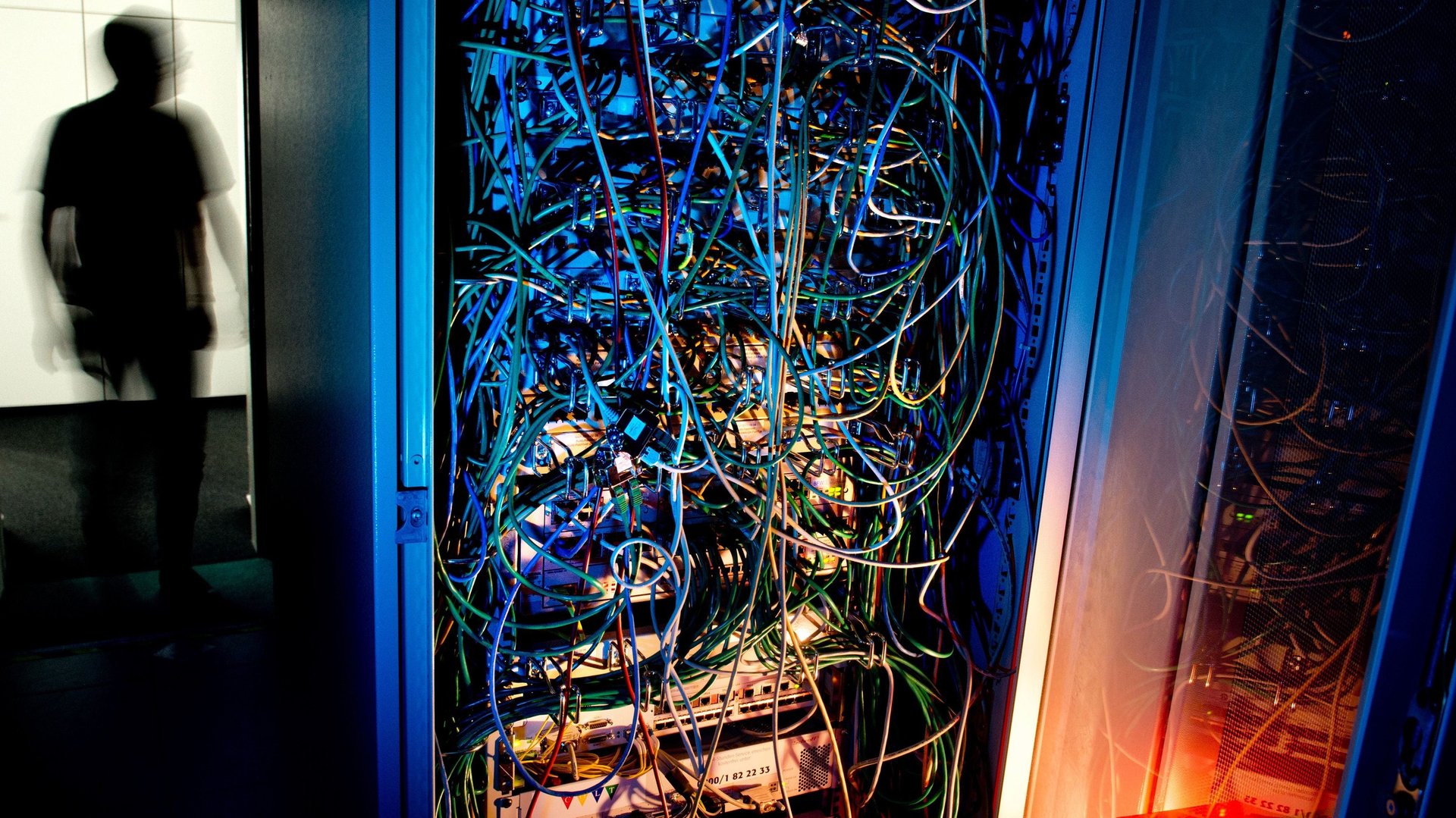

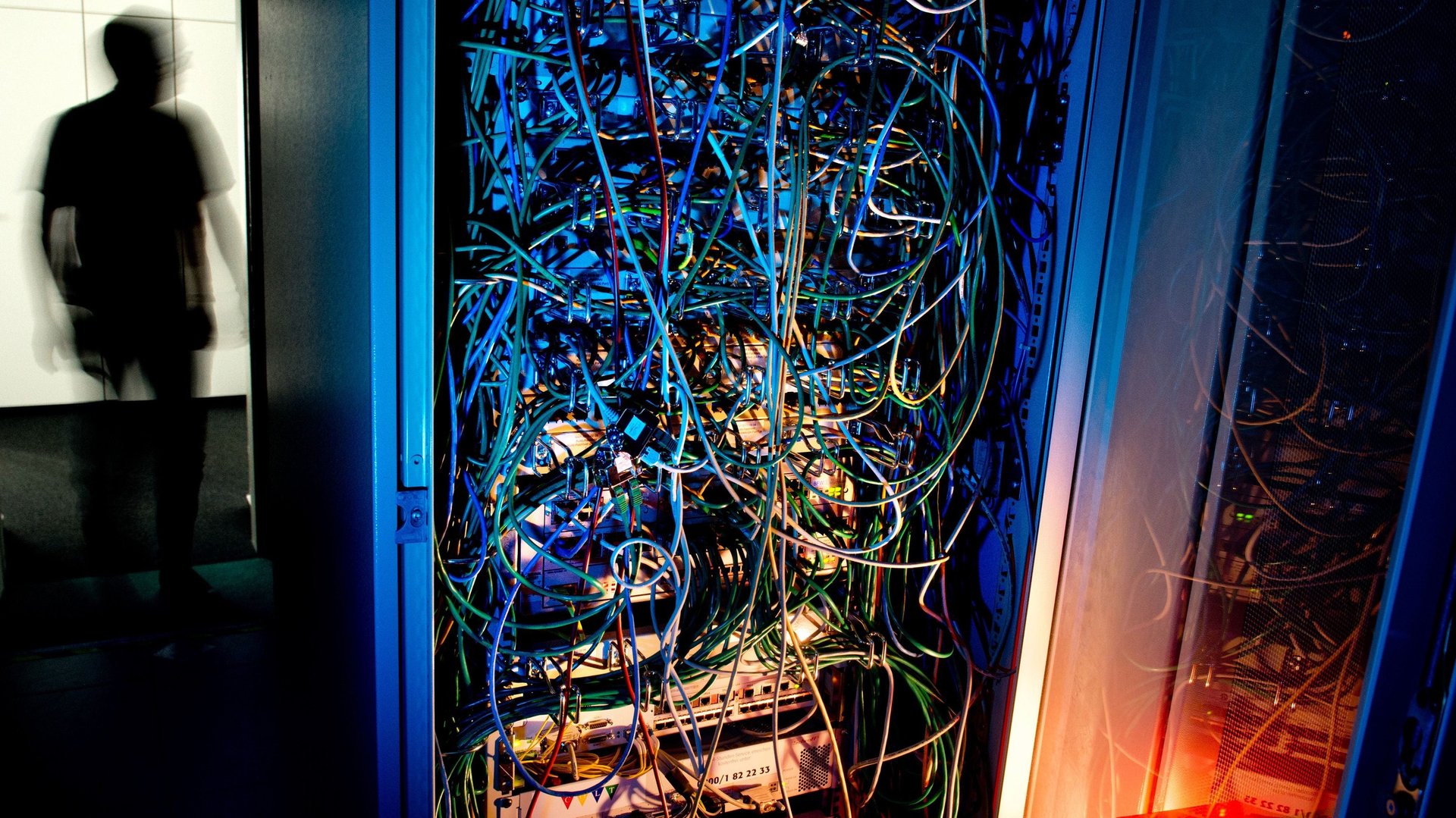

To meet this expectation, companies would need to spend huge amounts on setting up local servers, among other things. Experts believe this may become a big hurdle for existing companies to operate in India, and new ones to set shop. It will particularly impact foreign firms such as Facebook and Twitter, which already have millions of users in India but store their data at remote locations.

While bigger entities may manage to muster the resources to meet this requirement, India will become extremely undesirable for smaller players.

“Mandating localisation of all personal data as proposed in the bill is likely to become a trade barrier in the key markets,” IT industry body Nasscom said in an email statement. “Startups from India that are going global may not be able to leverage global cloud platforms and will face similar barriers as they expand in new markets.”

Besides, even if all companies were to comply with this requirement, experts argue, it won’t solve any purpose.

“Is the concern around (a) company owning the data, mining the data to its benefits? If so, how will localising the data help prevent it?” asked Rana Gupta, vice-president at cybersecurity firm Gemalto. “If the concern is around data protection, then data localisation without appropriate data protection regime wouldn’t serve any purpose.”

Limiting laws

“The central government shall, by notification, establish for the purposes of this Act, an authority to be called the Data Protection Authority of India…with power, subject to the provisions of this Act, to acquire, hold, and dispose of property, both movable and immovable, and to contract and shall, by the said name, sue or be sued.”

— Chapter X (Data Protection Authority of India), The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018.

[…]

“The data fiduciary shall notify the Authority of any personal data breach relating to any personal data processed by the data fiduciary where such breach is likely to cause harm to any data principal (user).”

— Chapter VII (Transparency and accountability measures), The Personal Data Protection Bill, 2018.

While the bill intends to improve transparency and accountability, this authority—comprising a chairperson and six other members appointed by the central government—would hardly operate autonomously.

“The bill provides excessive powers (to) the central government, especially under Section 98 which not only states that the central government can issue directions to the authority, but also that the authority shall be bound by directions on questions of policy in which the decision of the central government is final,” said Shweta Mohandas, programme officer at the Centre for Internet and Society, a Bengaluru-based non-profit organisation.

To worsen matters, the criminal liabilities making all offenses cognisable and non-bailable under this bill is worrying. “…enforcement that happens in fits and bursts will only make it tougher for businesses,” said Mishi Choudhary, legal director at pro bono legal services firm Software Freedom Law Center. “With little understanding of technology, sections are slapped, forcing companies and executives to deal with the criminal machinery.”

The bill does not provide a time period for businesses to comply with the provisions either.

A poor rip-off

On several counts, the proposed law is similar to the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union.

For instance, India has proposed that any company that fails to comply with the law will be fined Rs5 crore ($727,450) or 2% of its turnover, whichever is higher. The severity of this punishment mirrors that of the GDPR, which fines companies €20 million ($23 million) or 4% of turnover.

However, there are several differences, too. For instance, it does not allow Indians to ask companies to completely delete data they have shared, an accepted practice in the EU. The “right to be forgotten” suggested in the bill only allows individuals to restrict companies from using their data.

“The devil here is in the detail, we will need to know what is critical personal data,” Nehaa Chaudhari, a privacy lawyer with a technology law firm, told Reuters.

Also, India asking companies to localise data is far more complicated compared to the laws in the EU, experts say. “GDPR only requires you to have a local representative, which is a better approach,” Sunil Abraham, executive director at Centre for Internet and Society, told the Economic Times newspaper. “Then you can arrest the representative if FB (Facebook) doesn’t give you data, which is a better way for the government to force corporations to submit data.”