The painstaking, monumental task of mapping India in the 19th century

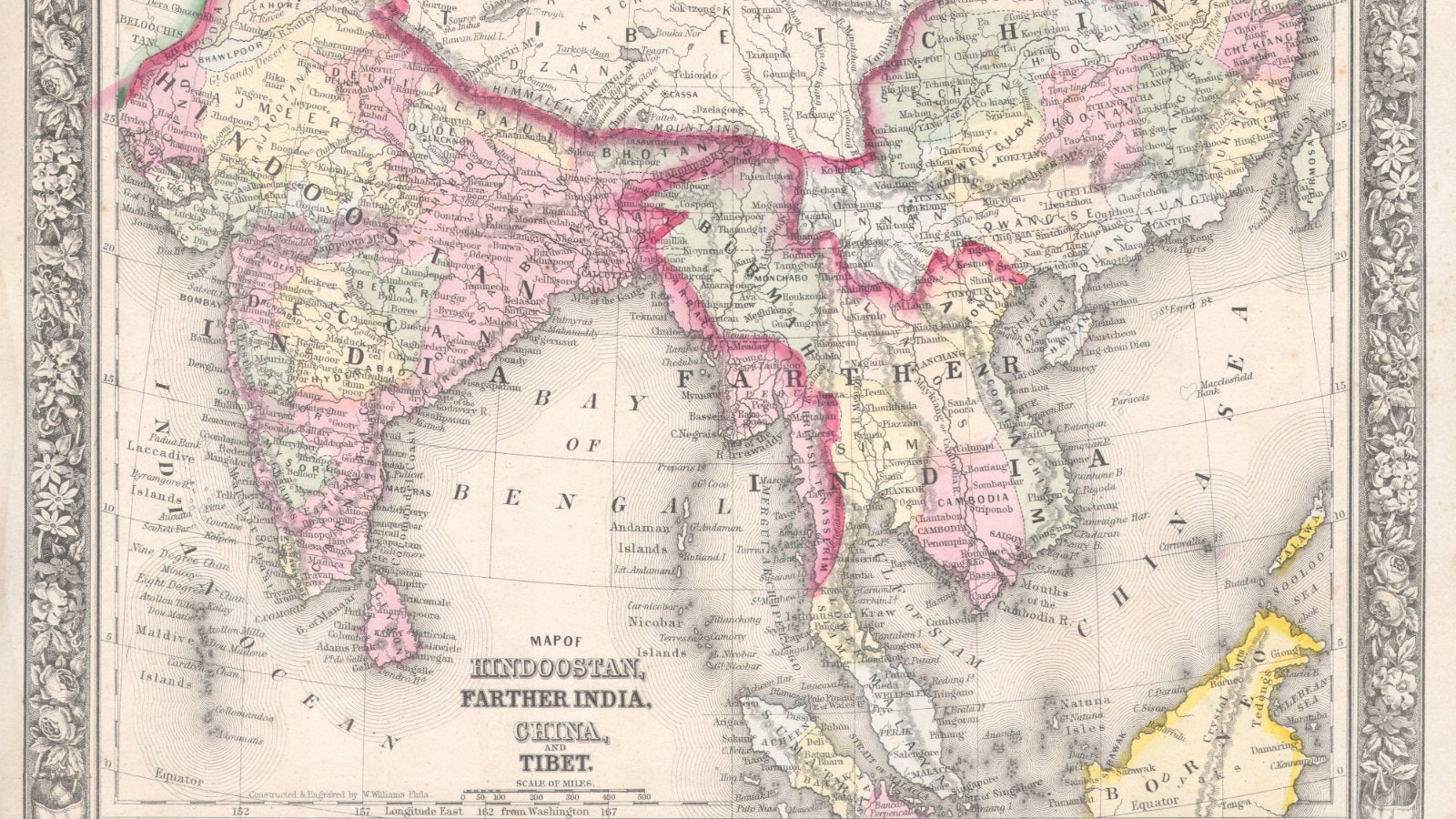

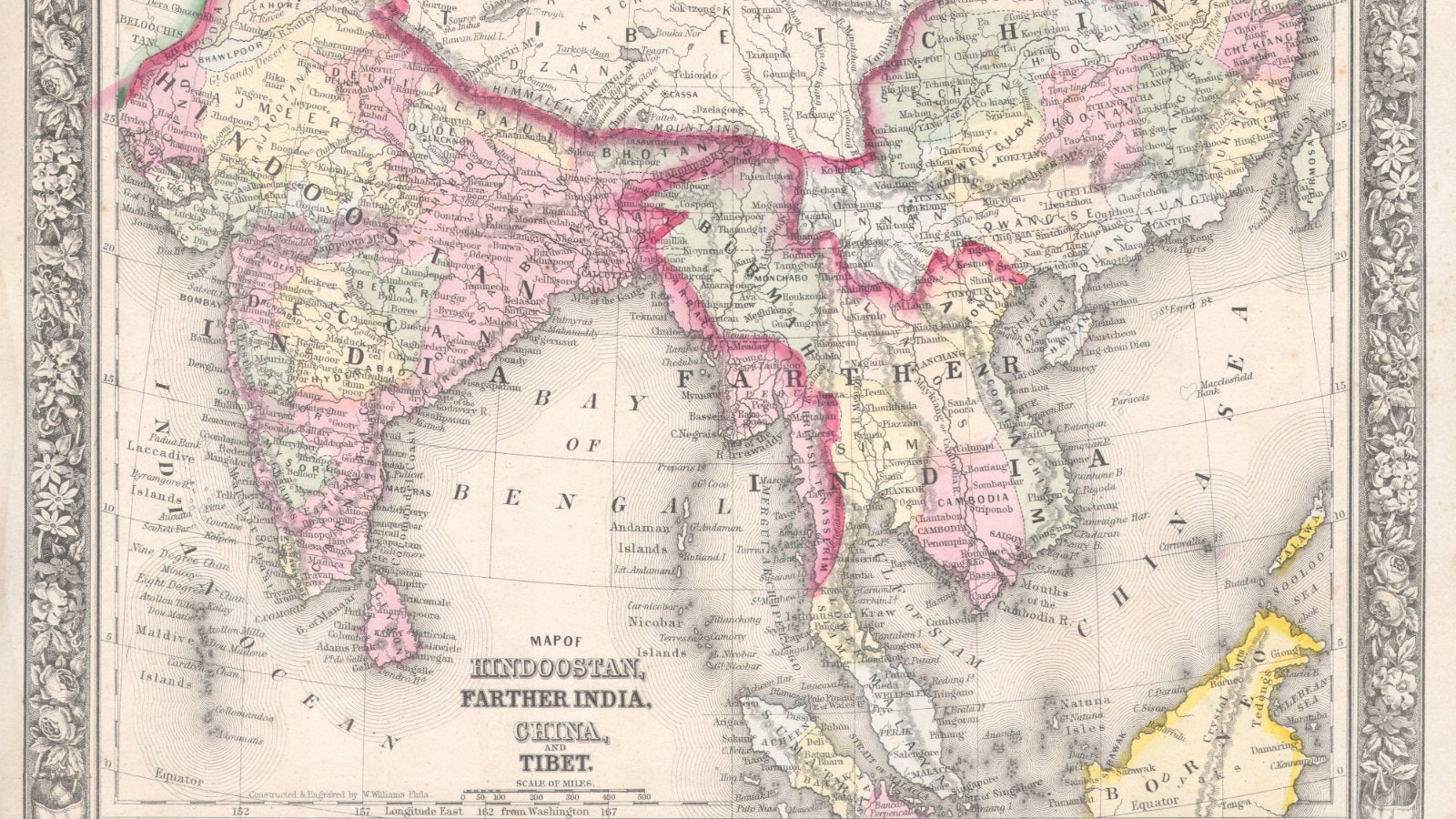

In 1800 a sweet-tempered and reticent Englishman had conceived the modest ambition of surveying all of India. To map India a team of surveyors, beginning at an observatory in the western port of Madras, crawled towards the southernmost tip of India, before returning for a northward sweep, roughly following the arc of the seventy- eight degree meridian. There were latitudinal forays to connect Madras and Calcutta on the east coast with Mangalore and Bombay on the west. Plagued by jungle fevers, floods, and wild animals, they steadfastly triangulated mile upon mile, year after year, using algorithms that took into account the curvature of the earth and the effect of heat on the links of the hundred-foot chain that established the seven and-a-half-mile baselines. The longest measurement of the earth’s surface ever attempted, the result was called the Great Indian Arc of the Meridian.

In 1800 a sweet-tempered and reticent Englishman had conceived the modest ambition of surveying all of India. To map India a team of surveyors, beginning at an observatory in the western port of Madras, crawled towards the southernmost tip of India, before returning for a northward sweep, roughly following the arc of the seventy- eight degree meridian. There were latitudinal forays to connect Madras and Calcutta on the east coast with Mangalore and Bombay on the west. Plagued by jungle fevers, floods, and wild animals, they steadfastly triangulated mile upon mile, year after year, using algorithms that took into account the curvature of the earth and the effect of heat on the links of the hundred-foot chain that established the seven and-a-half-mile baselines. The longest measurement of the earth’s surface ever attempted, the result was called the Great Indian Arc of the Meridian.

The use of triangles to estimate the distance between one point and another dates to antiquity. In order to survey a fixed area, lines of sight must first be established between three visible reference points. These three points demarcate the three points of a triangle, with the sight lines representing the three sides. The distance between two of the three points must be known. This is called the baseline. By measuring the angles made by the baseline with the angles of the sight line to a distant third point (a peak or a hill topped with a signal post), the distance and position of the latter can be established by trigonometry. Once its distance was determined, that side could be used as a baseline to fix the distance of another visible fixed point. Stations were thus added one by one, creating a web of triangles across the subcontinent. At critical junctures astronomical observations would be made to cross-check for accuracy.

For the Great Indian Arc, a theodolite weighing half a ton was used to measure the horizontal and vertical angles from each end of the seven-and-a-half-mile baseline to the fixed point. It required a dozen men to carry it. Where there was no fixed point on which to fix the telescopic sights of the theodolite, the survey team built one. Another man would see to the project’s completion, fifty years after it was begun. His name was George Everest. The highest fixed point in the world would be named after him.

A no less monumental achievement concluded half a century later. Upon winning the right to collect revenues, the East India Company had begun mapping every inch of inhabited, cultivated, and forested land in Bengal, registering the name of each landowner or tenant in logbooks. When, in response to the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the Crown bought out the company (adding its stiff price to the long column of India’s debt) the project continued. These cloth maps and logbooks were known as land records. Land records were tied in neat bundles, wrapped in red cloth, and stacked on floor-to-ceiling shelves running the length of the record room of the district collectorate. By the early twentieth century, there was a map for every village in India.

Every ICS (Indian Civil Services) officer spent one cold season learning the subtleties of land settlement recording. After his Midnapore posting (Michael John) Carritt had a stint. As soon as all the villages and fields in one district were surveyed, and the names, rents, and tenures recorded, a five-member team would move on to the next. As Bengal was made up of some 20 districts and each one took from two to four years to survey, Carritt had calculated it would take nearly 50 years to complete one round. Then the entire operation would begin again. Aerial photography to assist in drawing maps was, however, just coming into use. A light biplane flying back and forth along three-mile strips would generate a roll of images. These flights occurred in the morning or evening so that the shadows from the low mud walls surrounding each paddy could be seen and measured.

It was through land records and Survey of India maps that the Crown replaced ancient understandings governing the land with its own legalisms. The rights of hereditary ownership, from the lowliest cultivator to the most powerful landowners, could be taken away with the stroke of a patwari pen. The revised land record would then be wrapped again in red cloth and placed in the appropriate spot on the collectorate’s shelves. And there it would sit collecting dust until the land once again changed hands.

Excerpted with the permission of Penguin Random House India from The Last Englishmen by Deborah Baker. We welcome your comments at [email protected].