A century ago, postcards were the Instagram of the British in India

Annie and May Reynolds’ postcard correspondence between Madras and Birmingham from 1912 through 1919 is much like posts on a modern-day Instagram account.

Annie and May Reynolds’ postcard correspondence between Madras and Birmingham from 1912 through 1919 is much like posts on a modern-day Instagram account.

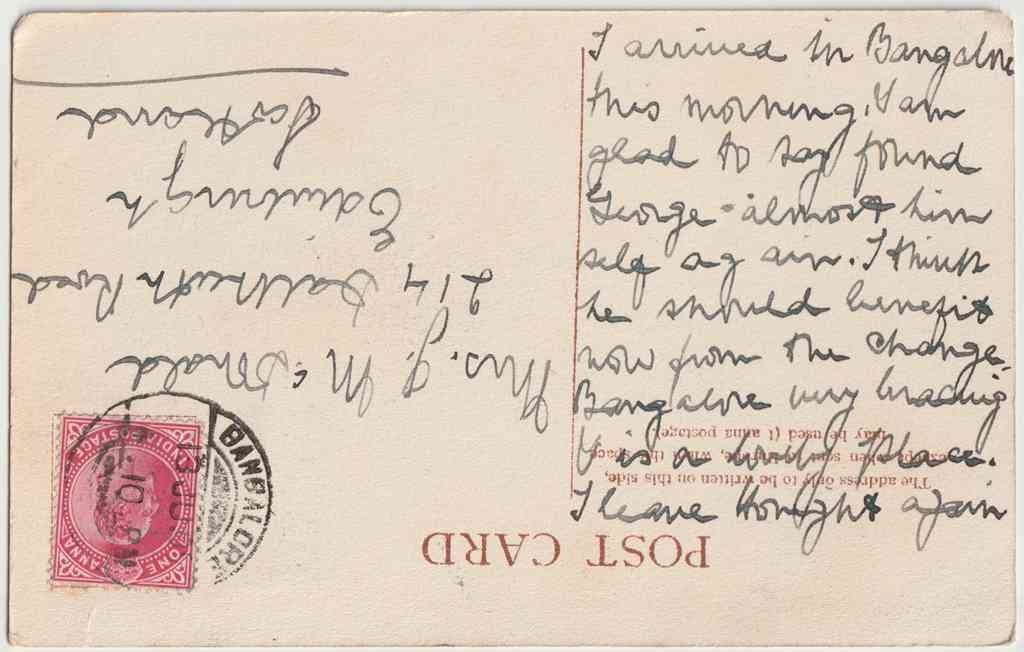

May, then a teenager, curated her aunt’s life in a postcard album, and the entries included images of holidays to the Nilgiris, Bangalore, and Mahabalipuram; local landmarks, and photographs of their daily life. In one picture, Annie’s son Billie is with his ayah and in another, carriages and cars are plying on Mount Road in Madras. Most postcards in the album carried short messages on sundry matters—Billie’s growth, Reynolds’ new car, the weather, or an explanation of the location pictured.

These and other vignettes from colonial Madras and Bangalore capture an orientalist nostalgia at an exhibition at London’s Brunei Gallery. From Madras to Bangalore: Picture Postcards as Urban History of Colonial India is co-curated by Dr Stephen Putnam Hughes and Emily Rose Stevenson from the department of anthropology at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS). The exhibition, which is on till Sept. 23, is supported by the Economic and Social Research Council and the SOAS South Asia Institute.

“Postcards were the Instagram of the early 20th century,” said Hughes, who has been collecting them from ephemera fairs, through family connections, and online auctions for over 20 years.

Colonial encounters

From the 1900s to 1930s, postcards served as an affordable and popular means of mass media for Europeans living in colonies to keep in touch with families and friends at home. “These were the years when postcards were at the height of their popularity,” said Stevenson, whose collection efforts span the last five years. “They were a new media craze that swept the globe.”

While there are just over 300 postcards on display at the exhibition, over 1,000 postcards from the curators’ private collection were examined to understand “how postcard practices imagined, figured, and performed a colonial encounter through the cities’ monuments, streets, people, and places.”

The power of images as a mass medium cannot be overstated: between 1902 and 1910, nearly six billion postcards passed through the British postal system alone. When compared to Instagram, which has over a billion users with over 40 billion photos and videos, these fragments from the colonial era serve as a reminder of how material practices surrounding visual media have transformed and transcended through time.

Essential to the trade and consumption of postcards were the production circuits in India, which formed a part of a global network spreading across countries like Germany and Italy. Bangalore and Madras back in the early 1900s had an extensive network of photographers, apprentices, and studios populated and run by Europeans and Indians. Postcards produced in such studios, of which none remain today, were circulated and reproduced globally.

According to the curators, while further research is required in this area, Indian photographers and studio owners in the trade attempted to create an Indian market for postcards. This expansion is evidenced in the increased use of postcards by Indians around the 1930s, and the bilingual postcards captioned in English and Tamil.

The mechanics of production didn’t just shape the trade, but also the representation of the imagery on the postcards, be it street scenes and monuments, public and private life, religion occupation, or leisure.

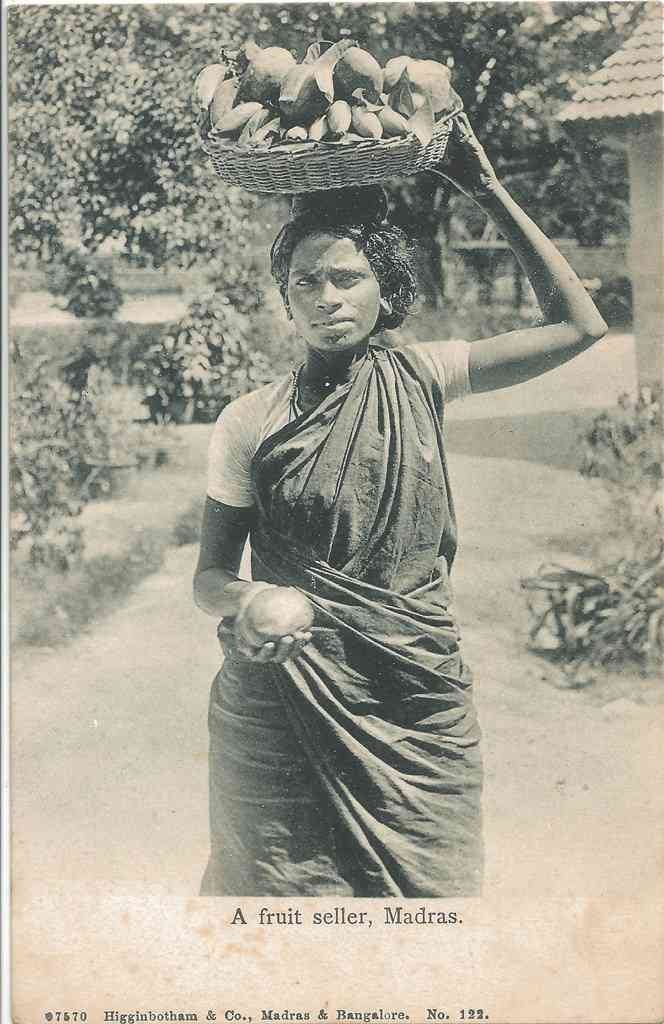

Portraits of Indians, or the natives of Madras and Bangalore, were identified not by names but by ethnicity, gender, religion, or caste, and most often by their means of employment. “This was a dominant way Europeans and Americans visually represented the otherness of non-western people in popular visual culture, scientific studies, and colonial administration throughout the 19th and into the 20th century,” said Hughes. There are a large number of postcards in the exhibition depicting servants who worked for Europeans living in Bangalore and Madras. Personalised postcards of family members and children with ayahs were popular among the British middle–class.

Personalised punchlines

The decision to include the racial politics of British Indian postcards in the exhibition was taken after much debate and a roundtable discussion, says Hughes. Excluding them would be to sanitise the history of British Indian picture postcards, Stevenson adds.

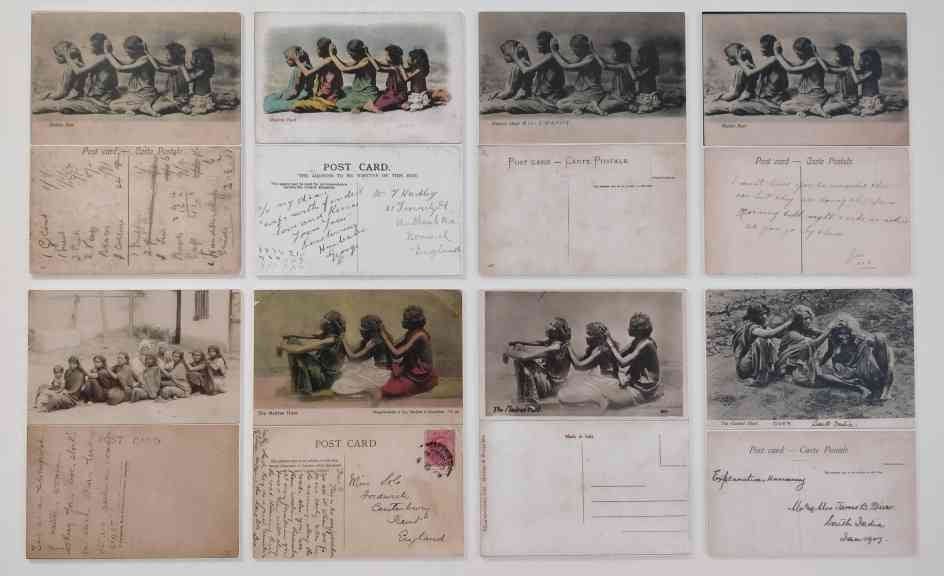

On display are series such as the Madras Hunt and Masters, which were hugely popular during the time but have strong racist overtones. The Madras Hunt series, published by Higginbotham & Co. of Madras in the early 1900s, show women and children delousing each other along a street side. It was not only photographed and produced in India, but also printed in Germany, Italy, and England. Many of the photographs on the postcards are staged, and the messages behind them range from wisecracks to shopping lists. Not only did Higginbotham’s produce multiple versions of the series, smaller studios such as D Payanivalu Mudr in Ulsoor, Bangalore, published similar postcards highlighting the popularity of the motif.

Similarly, the Masters series, also published by Higginbotham & Co., staged scenes where Indian servants mimicked their British masters. Here, Indians are shown taking liberties with their employers’ possessions, luxuries, and comforts, thus playing on the insecurities and anxieties of a ruling class. As the exhibition panel notes, both the Madras Hunt and Masters series were “visual jokes waiting for a personalised punchline to be added by their users,” much like the memes used on social media.

The curators say that they do not want to lecture visitors on the critique of colonialism, but pose some questions and provide enough information to help them do the work of decolonisation.

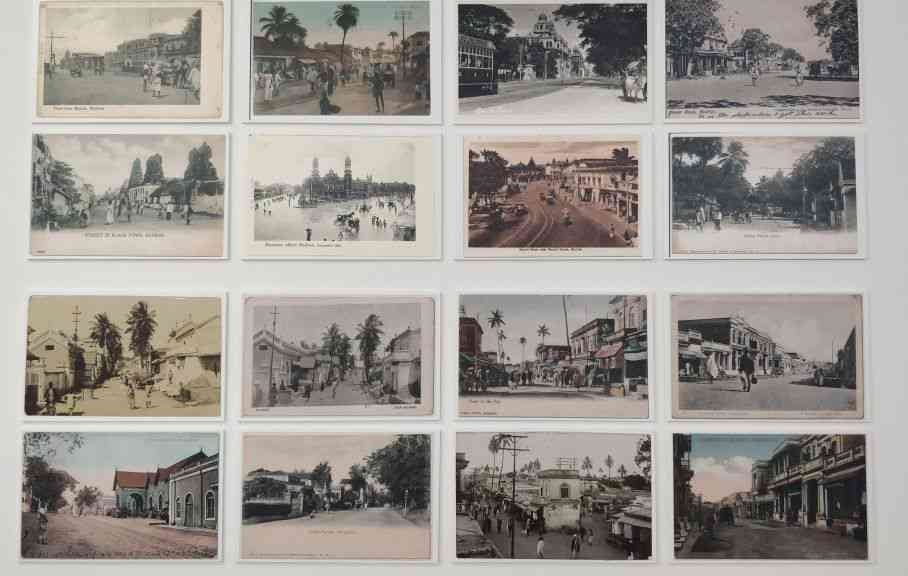

It is with this same subtlety that the exhibition explores the construction of the colonial urban landscape through postcards. Two panels locate select postcards on old maps of the two cities. This geo-tagging-like exercise allows the viewer to understand colonial urban planning and the social lives of the people.

In continuation with the tradition of European landscape painting, the picturesque photographs represent deserted monumental buildings such as law courts, museums, churches, post offices, parks, stations, and clubs, all of which emerge from the European settlements. Those of natives in front of temples, rivers, streets lined with coconut trees or such, emerge from outside these settlements. Neither Europeans nor Indians inhabit these vistas of perfect colonial creation. If at all humans are present, such as in the postcards of the post office in Bangalore or the Esplanade in Madras, the motley crew is dwarfed by the structures behind them.

The curators say that the monumental visualisation was intended to convey the power and glories of British rule, and enact a link to the empire. By focusing on the imposing city and the edifices of British rule, the postcards ignored multicultural interactions, enabled by the same institutions and urban scapes, rendering them incongruous in the public imagination.

“Postcards reflect British understandings and planning of cities in India, which was based upon European distinctions between public and private space, and divisions between Indian and European populations,” said Stevenson.

Hughes and Stevenson have taken their curating duties to Instagram, where @soaspostcard acts as a postscript to the exhibition. It merges an older form of pictorial mass communication with the latest, showcasing select postcards with detailed analysis or captions. There are plans to take the exhibition to Chennai and Bengaluru, and efforts are on to raise funds for the trip.

At the end of the exhibition is a rack of free postcards that visitors can send out. Stevenson urges visitors to pick one for feedback or to send it to friends. I send one to a friend who said of the medium, “It never ceases to amaze me that something as easily misplaced or destroyed as a piece of paper can be sent all the way across the world.”

This piece was first published on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].