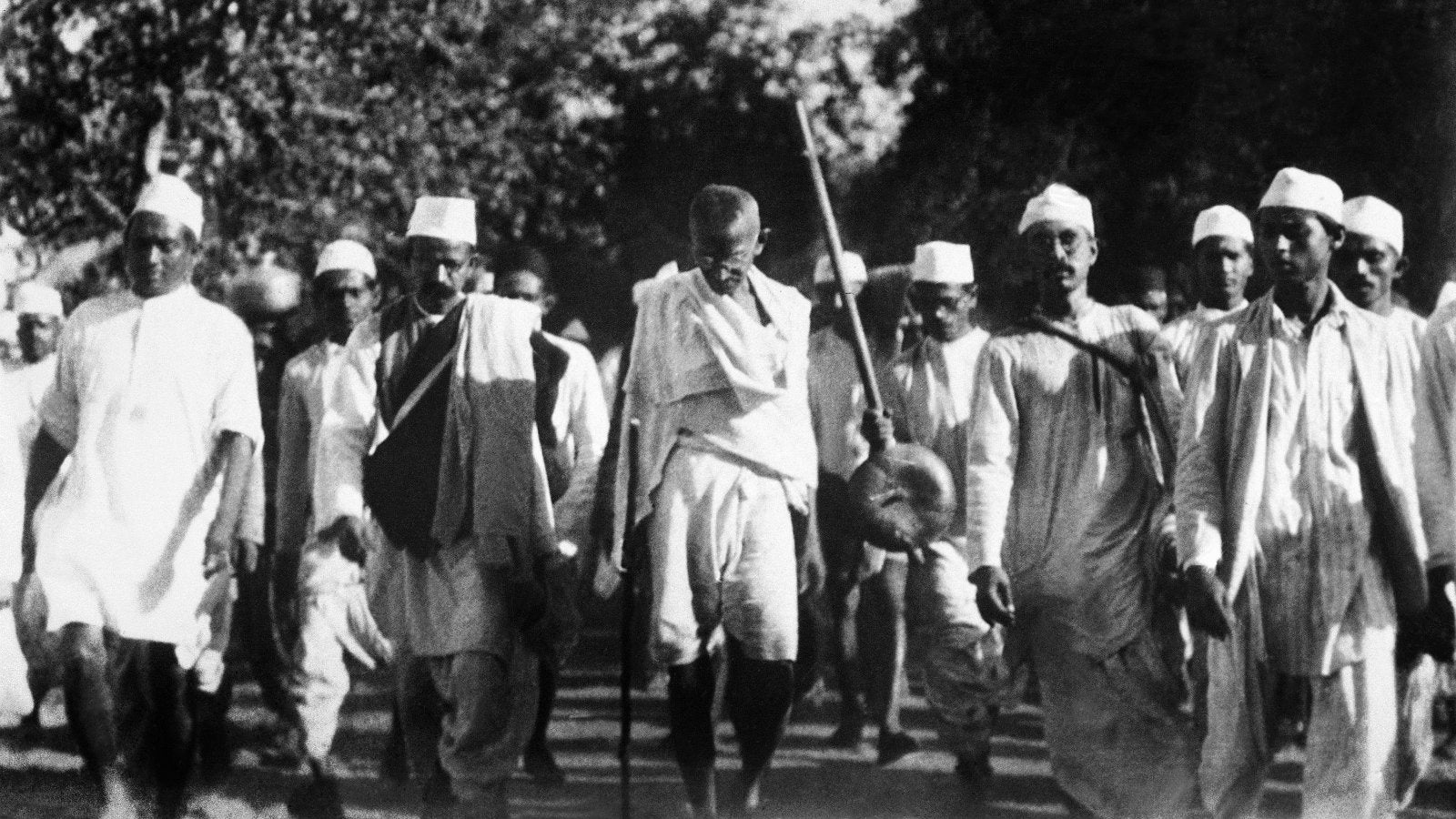

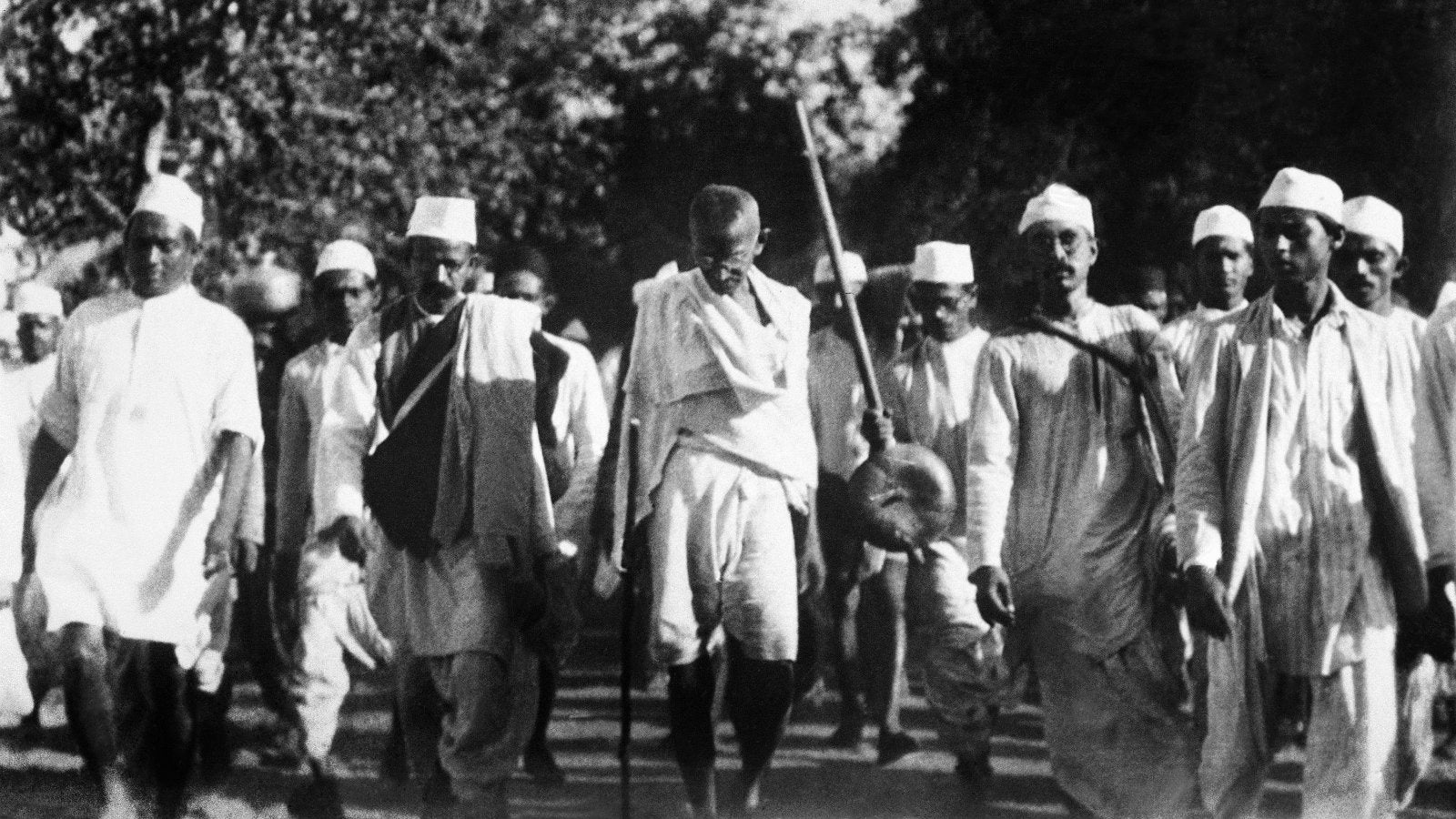

How Gandhi gave India a sense of dignity and national purpose

After a visit to Yerwada prison in August 1932, the respected newspaper editor SA Brelvi called Gandhi “the truest nation-builder since (the Mughal emperor) Akbar’s time,” adding, “of the two (he) will prove to be the greater.”

After a visit to Yerwada prison in August 1932, the respected newspaper editor SA Brelvi called Gandhi “the truest nation-builder since (the Mughal emperor) Akbar’s time,” adding, “of the two (he) will prove to be the greater.”

In 1932, the independence of India lay many years in the future. But as a close observer of Gandhi’s politics, Brelvi understood how he was nurturing the nation-in-the-making. He had seen Gandhi build bridges between Hindus and Muslims, take the nationalist message to the south and east of the country, urge that “untouchables” be treated as equals, and steadily undermine the patriarchy which characterised India’s two major religions, Hinduism and Islam.

India today is a flawed and fault-ridden democracy. Its many failures include widespread poverty, the malfunctioning of public institutions, political corruption, and crony capitalism. On the other side, unlike so many ex-colonial countries, India regularly conducts free and fair elections; women have equal rights under the constitution; it has successfully nurtured linguistic diversity; the state is not (or not yet) identified with a particular religion; and it has extensive programmes of affirmative action for those of underprivileged backgrounds. These achievements are owed to a generation of visionary nation builders, among whom Gandhi was—in all senses—pre-eminent.

Gandhi’s successes in forging a sense of dignity and national purpose were in large part a product of his methods. A country so large, so staggeringly diverse, and so desperately divided could never have been united by a leader (or leaders) marked by ideological rigidity or personal arrogance. Travelling through India in 1938, meeting Gandhi and studying his work, talking to his followers and his critics, the American journalist John Gunther came to the conclusion that perhaps the most striking thing about Gandhi was “his inveterate love of compromise…Surely no man has ever so quickly and easily let bygones be bygones. He has no hatreds, no resentments; once a settlement is reached, he co-operates with enemies as vigorously as he fought them.”

Gandhi himself expressed it slightly differently. In November 1936, an English visitor to Sevagram asked for details of Gandhi’s village programme. He answered: “I cannot speak with either the definiteness or the confidence of a Stalin or Hitler, as I have no cut-and-dried programme I can impose on the villagers. My method, I need not say, is different. I propose to convert by patient persuasion.”

Promoting an ethic of dialogue and compromise was one way in which Gandhi brought different kinds of Indians together. A second was through the Congress Party, which, under his direction, transformed itself from a body of urban middle-class professionals into a mass political organisation, with branches in states and districts, its networks touching every part of India and virtually every section of Indian society. By promoting the mother tongue, Gandhi drew peasants, workers, and artisans into a continuing conversation with lawyers, businessmen, and intellectuals.

The social base of the Congress was far deeper than that of the Muslim League, one reason why democracy has established itself more solidly in India than in Pakistan, a point that some Pakistani scholars themselves acknowledge. Another key difference between Gandhi and his great rival Muhammad Ali Jinnah was that the former assiduously nurtured leaders for the future, whereas Jinnah was verily the Great and Only Leader. There were no analogues in his party of Nehru, Patel, Rajaji, Azad, and others.

That, amidst the wreckage of Partition, there were some capable men and women at hand to build a nation anew was largely the handiwork of Gandhi. I have already spoken of the partnership between Jawaharlal Nehru as prime minister and Vallabhbhai Patel as home minister. A third Gandhi associate, Maulana Azad, served as education minister; a fourth, Rajkumari Amrit Kaur, as health minister. Formally placed above them all, as the President of the Indian Republic, was Rajendra Prasad, whose potential Gandhi first saw in Champaran in 1917.

One of Gandhi’s closest colleagues, J B Kripalani, left the Congress shortly after Independence to start his own party. A second, C Rajagopalachari, served as the governor of West Bengal and as the last governor general while the country was still a dominion, and as home minister of India and chief minister of Madras province after the country became a republic. However, he became increasingly disenchanted with Nehru’s policies, and in 1959 formed a new party, Swatantra, promoting the values of market liberalism in opposition to the centralized economic planning that the prime minister favoured. Meanwhile, as an opposition member of Parliament, J B Kripalani was relentlessly harrying Nehru on his appeasement of Chinese communism.

Gandhi himself had little interest in constitutional processes or the functioning of Parliament. But indirectly, he played a considerable role in stabilising the democratic institutions of independent India. Through the 1950s and 1960s, some of the men and women he had trained ran the ship of state, while others were in the Opposition, holding the government to account. It was also followers and admirers of Gandhi, such as Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and J C Kumarappa, who laid the foundations of the civil society movement in India, by working to promote cooperative housing projects, revive traditional handicrafts, and renew the rural economy.

As the major leader of the freedom struggle in the largest colony of the world’s greatest empire, Gandhi also profoundly influenced anti-colonial movements elsewhere. Gandhi was admired by such (widely different) African nationalists as the Kenyans Jomo Kenyatta and Tom Mboya, the Zambian Kenneth Kaunda, the Tanzanian Julius Nyerere, and the Ghanaian Kwame Nkrumah. In Botswana, when the British exiled the extremely popular king, Seretse Khama, chiefs and headmen refused to elect a new leader, and said they would not pay taxes unless Seretse returned with his honour and position intact. Their movement of civil disobedience was inspired by their knowledge of the satyagrahas led by Gandhi in India and South Africa.

In South Africa itself, the struggles against apartheid were directly inspired by Gandhi. The long-time leader of the African National Congress, Albert Luthuli, counted himself a disciple of Gandhi, and so, less surprisingly, did leaders of the Indian community such as Monty Naicker and Yusuf Dadoo. The first major mass movement against apartheid, the Defiance Campaign of 1952, used methods pioneered by Gandhi, with African and Indian protesters defying racial laws by entering offices, train compartments, and other public spaces designated for ‘Europeans only’.

In 1960, the African National Congress (ANC) abandoned nonviolence. For the next thirty years it practised various forms of armed struggle. But the Gandhian element returned after the release of Nelson Mandela in 1990 and the negotiations for the transfer of power. After the ending of apartheid, and his taking office as the first president of a democratic South Africa, Mandela promoted a Gandhi-like path of reconciliation with the white race, and among the different sections of South African society. That the constitution of democratic South Africa refused to privilege a particular race, religion, or linguistic group also owed something to the Indian, or one might even say, Gandhian, experience.

Excerpted with the permission of Penguin Random House India from Gandhi: The Years that Changed the World by Ramachandra Guha. We welcome your comments at [email protected].