Facebook takes down Indian political ads because they don’t list who paid for them

Roiled by scandals over the past two years, social media giant Facebook is trying hard to be transparent about how it runs political advertisements.

Roiled by scandals over the past two years, social media giant Facebook is trying hard to be transparent about how it runs political advertisements.

But, in some ways, these efforts only raise more questions—especially for users in India.

Facebook’s new Ad Library is one step in the company’s pursuit of greater transparency. The digital archive, for which Facebook has been compiling records since May, allows users to see any ad that is “related to politics or issues of national importance.” For now, Facebook claims the archive lists only ads viewed on its platform by users in the US, the UK, and Brazil.

Each entry about an ad includes information about how much the advertiser spent on it, how many people have seen it, and what its audience’s demographics are, including a breakdown by age, location, and gender.

Facebook reportedly plans to roll out the ad archive for India but is still evaluating how best to do so.

Strangely, though, some of the entries in the library seem to be Indian ads targeting an Indian audience, despite the portal not being released in India yet. These can stray far from simple political advertising, ranging from ads for tourism destinations to ads for charities. Often, the archive indicates, Indian ads are removed from Facebook because they do not list who paid for them.

Defining “politics” and “national importance”

In the Ad Library, Facebook includes a note above all ads that were removed because they did not specify their buyer. The note reads:

This ad ran without a “Paid for by” label. After the ad started running, we determined that the ad was related to politics and issues of national importance and required the label. The ad was taken down.

It is unclear how aggressively Facebook India has communicated to advertisers about how they need to list the name of the person or entity who paid for the ad if that ad is related to politics or “national importance.” The frequency of such ad takedowns for Indian advertisers certainly seems to indicate widespread ignorance on this point.

Facebook hasn’t yet formalised a process for Indian advertisers to become authorised to run politics-related content; so far, like the Ad Library, this has only been officially made available for the US, the UK, and Brazil.

This lack of a formal process ends up being harder on Indian advertisers, and any others outside those three countries. For the authorisation of politics-related ads in the US, for example, Facebook provides a list of 20 “issues of national importance,” which includes terms like “energy,” “guns” and “taxes,” demarcating the topics that, if mentioned, would require an ad to be labelled as politics-related. Indian advertisers, by contrast, are casting about in the dark.

Facebook did not respond to an emailed questionnaire from Quartz.

The process for judging whether the content is political or not is also extremely difficult, especially in the Indian context. “It’s hard enough in the US, it’s much harder in India,” a former employee of Facebook India told Quartz. Filtering out political content, the person said, requires developing a cache of keywords and identifiers, which “is not an automated process—that is a very manual process, and that is exceedingly hard in India because you have to go across linguistic boundaries.”

In the US, Facebook’s Ad Library has already been criticised for flagging certain non-political content as political, such as ads that mention African Americans and Hispanic people, as well as a benefit for rescuing dogs.

The Indian ads that were removed from Facebook because they did not list their sponsor range from conventionally political to seemingly apolitical. On the more political side, for example, is this ad for an infographic about the ongoing Rafale controversy, and an ad for a BJP parliamentarian’s official Facebook page.

These, and all the other ads whose screenshots are below, are listed in the archive as having been seen by an entirely Indian audience:

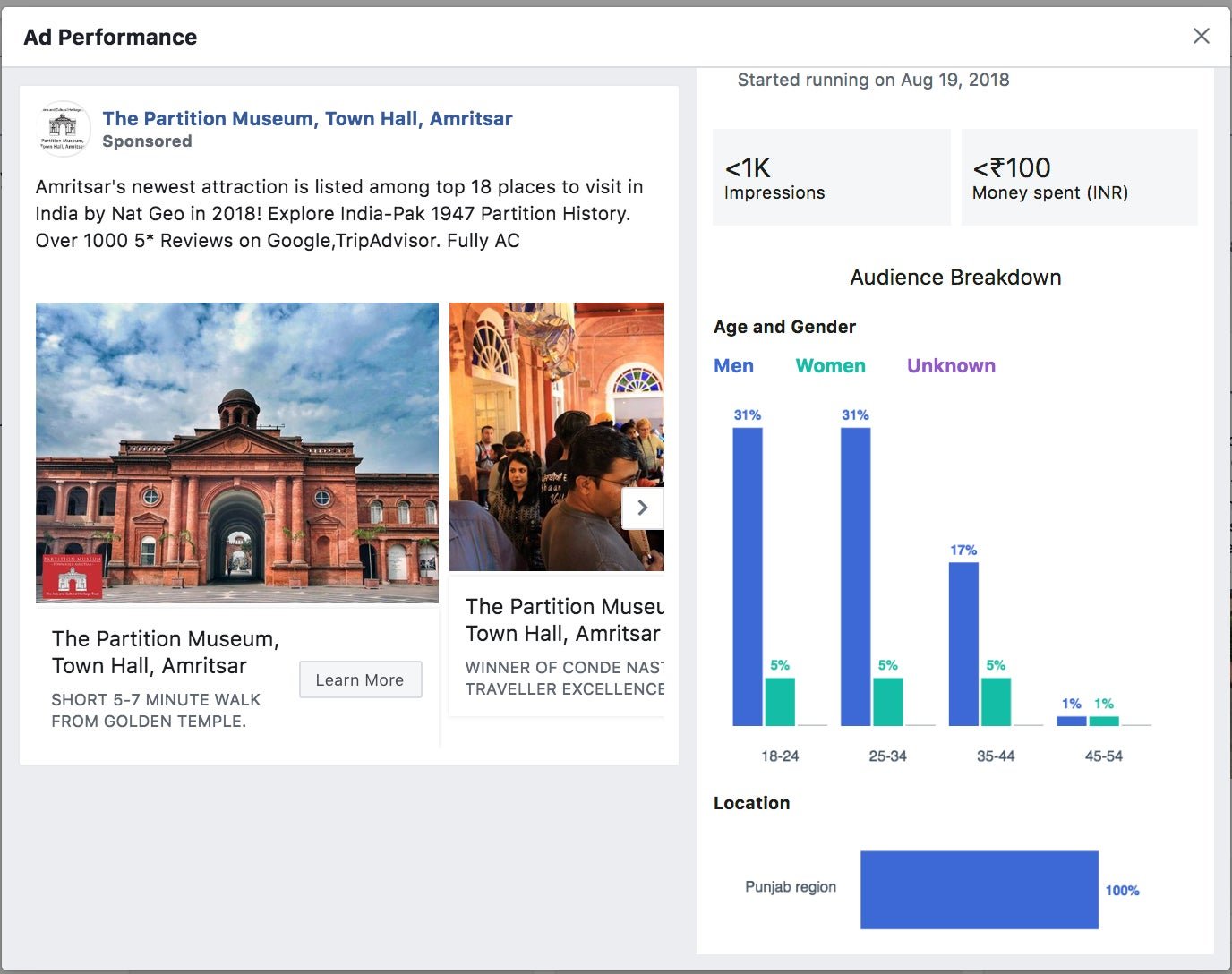

But tourism-related ads were often thrown up in the scanner as well, such as this advertisement for a museum in Amritsar, Punjab:

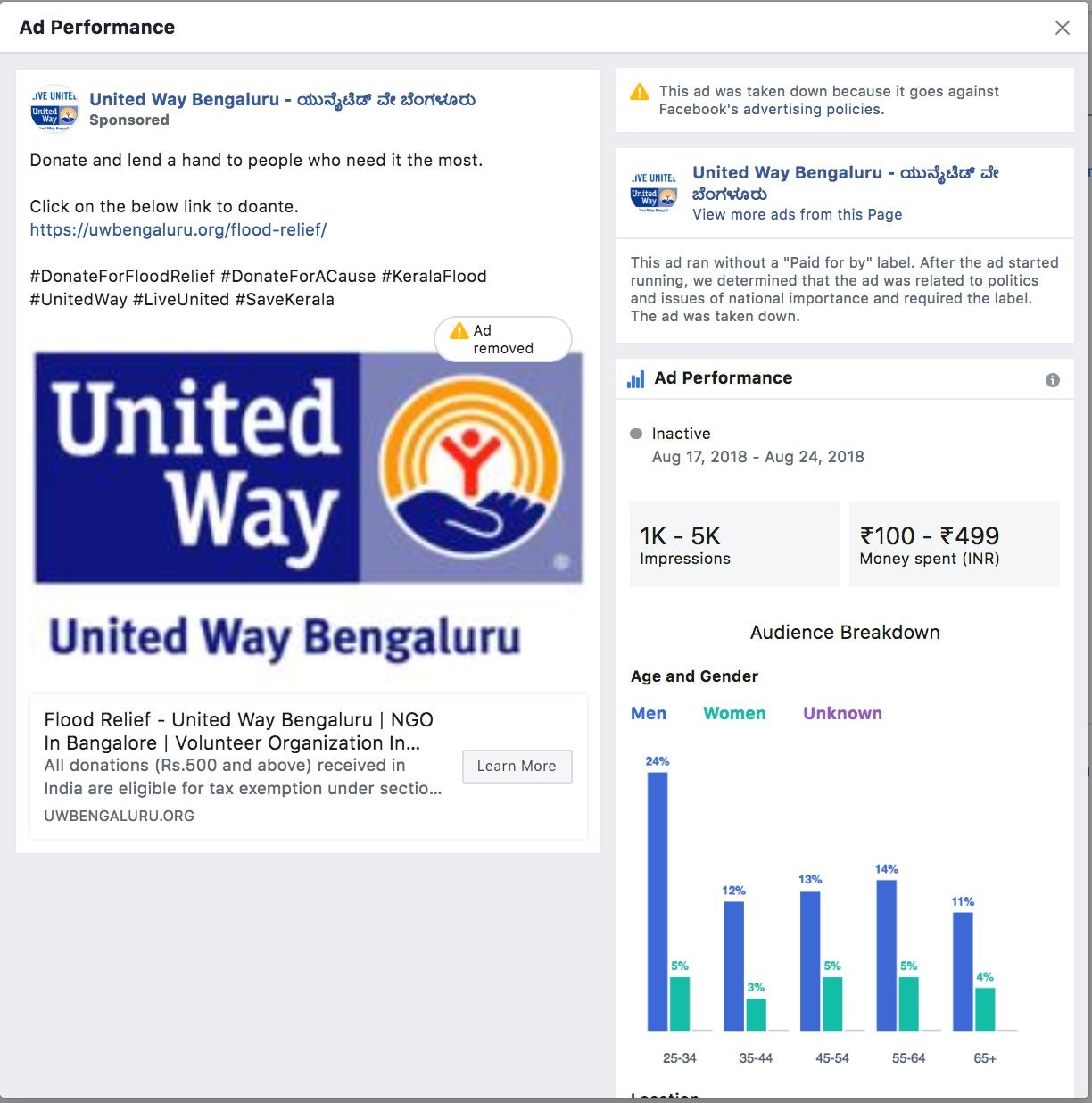

Some of the most dangerous collateral damage in this struggle for transparency seems to be ads for charities. The archive contained several advertisements by NGOs or other charitable organisations that had been pulled down, including one for relief efforts after this year’s disastrous flooding in Kerala:

Even this advertisement by the well-known charity, Save the Children India, was pulled down within two days:

Facebook’s misfiring algorithms have also impacted the operations of news outlets in India. Several of the Indian ads caught in Facebook’s dragnet were promotions for pieces in Asia Times, a digital news outlet. According to Saikat Datta, an editor of Asia Times, Facebook’s algorithm has not only repeatedly flagged their content but attempts to appeal it has been frustrating as well.

“Facebook is extremely opaque in their responses, and some of the justifications that they offer have no relation to the content of the story,” he said. “This makes Facebook a censor, and also restricts the freedom of the press.”

Dipayan Ghosh, a researcher at the Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Centre, who was formerly a public policy advisor at Facebook, described how the system the company uses to determine whether content is political is “causing serious hurdles for news organisations as they’re trying to just get people to see their content. When it’s flagged as political, and yet they’re not advocating a position on something, there’s something that’s clearly gone wrong in the system.”

Follow the money?

Even in countries where Facebook has rolled out the Ad Library and a process for authorising political ads, it is easy to game the system with surrogate buyers.

In the run-up to the US’s midterm elections, a limited liability company spent millions of dollars on political Facebook ads, listing its name as the ad buyer without ever disclosing that it was effectively a shell for another company, said a report in The Atlantic on Oct. 17. The amount of information that Facebook publicly discloses about ad buyers, in any case, is minimal.

In India as well, political ads and their funding are extremely difficult to track, because operatives from each party run many different “surrogate Facebook pages” and use them for different targeted campaigns, said Pratik Sinha, co-founder of the Indian fact-checking website AltNews. “The funds come through some other sources, but eventually they’re all going to party propaganda.”

Ghosh said that transparency efforts like Facebook’s Ad Library, while helpful, are only a small part of the way forward. “Transparency is helpful because it helps the people who are going out and looking for misuse of these platforms and propagation of nefarious content. It helps those people, such as researchers and journalists and other companies trying to learn. But for the average person, it really does nothing.”

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.