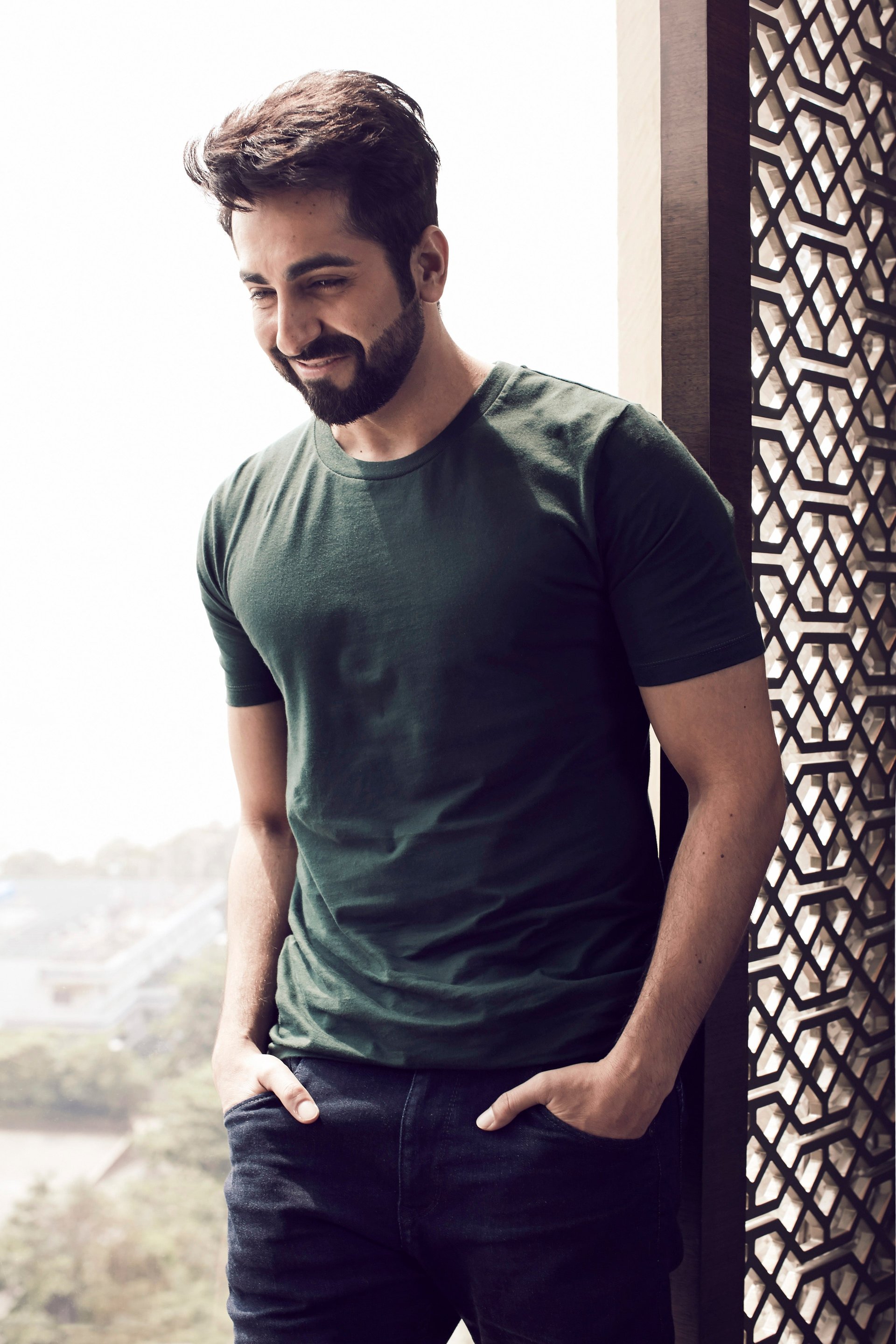

How a Bollywood star with no godfathers made it big with fresh ideas

Ayushmann Khurrana is on a roll.

Ayushmann Khurrana is on a roll.

The actor, born to an astrologer father and homemaker mother in Chandigarh, had two movies overlap at the box office this month and both have performed remarkably. The Sriram Raghavan-directed thriller Andhadhun, released on Oct. 05, has so far amassed Rs60 crore ($8.2 million). Meanwhile, Khurrana’s Oct. 19 release, a slice-of-life comedy called Badhai Ho that deals with pregnancy late-in-life, has also gathered over Rs60 crore at the box office and is on track to enter the coveted Rs100 crore-club—an elite benchmark of success in Bollywood.

But it took Khurrana over a decade to taste such success.

Over the last 16 years, he has lived many lives, from being a contestant on reality TV shows like Channel V’s Popstars and MTV Roadies to doing television soaps with production house Balaji Telefilms to becoming one of India’s most popular video jockeys (VJ).

Getting his first film was quite the task as well. Before his big break with Vicky Donor (2012), Khurrana had passed on four or five scripts already in search for the right one.

That smashing debut was followed by a lull.

“Immediately after my first film, I was really lost. Vicky Donor had set such a benchmark, I was not getting the right script of that level at all. Then I was going with the project, that this is the leading lady, this is the director, this is the writer, a big production house is backing it, let’s go for it—which was not the right attitude,” he told Quartz during at interview on Oct. 25. “It’s the script that works. In the past six years, that’s been the greatest learning experience.”

Below are edited excerpts from Quartz’s conversation with Khurrana:

What do you think has made you a successful Bollywood hero?

The real hero is the one who curates good content. I’ve taken that cue from (veteran actor) Aamir Khan.

Apart from that, it also comes from your gut and intuition. The kind of upbringing I had, I’ve been in touch with every kind of person in this world because my family is very diverse. We have the middle class, the lower class, the upper class—like there are cousins in the US and Canada, they’re super rich; then there are poorer cousins. But everybody’s part of the same family. That gives you a larger perspective on life and a lot of material. I have a varied sense of humour. I can play a high-class person, and a low-class person, too. I can be everybody.

Many of your films have delivered social messages, be it on sperm donation or body shaming. Is that a conscious decision?

Commercial value comes from entertainment. It doesn’t matter if you’re playing a guy who is bashing up 10 goons or maybe dancing around trees, it all boils down to entertainment. But the biggest draw is the subject—how unique is the subject, how novel is the idea. This has been the thread throughout, from Vicky Donor to Dum Laga Ke Haisha to Shubh Mangal Saavdhan to Bareilly ki Barfi to Andhadhun to Badhai Ho. I will choose the scripts which have no reference point in Hindi cinema.

Why did you pass on so many films before picking your first one?

When I was an anchor, a VJ, interviewing a lot of celebs and actors, I was very objective. I used to see the industry as an outsider. I always had the viewpoint that it’s really important to choose the right script to begin with. Since I was not a star kid, it was very important to choose the right first film as I knew I’ll not get another chance.

How hard does an outsider like you have it in Bollywood?

It’s changing. This is the best time to be in the industry. We’re very fortunate to be part of this era. Twenty years back, if I were a struggling actor, I would’ve only done TV and nothing else. All these big production houses were really unapproachable at that time. Now, the casting system has become so democratic that if you’re talented, give a screen test. If you’re good, you’ll get selected.

Also, as an outsider, you don’t have to live up to a certain legacy. You don’t have any baggage. Even if you achieve 70% of your self, you’ll be considered a success. Somebody with a big legacy, giving his 100% is still not good enough. They may get the first release, their first chance—of course, that’s huge—but I think it’s tougher for them.

Speaking of changes in Bollywood, what is your take on #MeToo?

I think it’s a great movement. It’s high time we do this—have guidelines within workplaces, have dos and don’ts. Especially when we go outdoors, women should feel safe when they’re shooting late nights. Men should understand that consent is key. On a moral basis, I think, you just need to bring up your sons well.

Having said that, equal opportunity should be given to both the parties to clarify their stands because collateral damage will also happen in this scenario.

You’ve been part of many multi-actor films. Do these help or hurt star power?

There are only pros. I’ve idolised Aamir Khan. He’s the one who put these two girls, newcomers, on a pedestal in Dangal, and he was in one cellar in the climax of the movie. He’s done Secret Superstar, he’s done a Taare Zameen Par. So it comes with the security in your head. If the film works, you are the one benefiting from it the most. I come from a theatre background where every character shines bright, gets the spotlight. How does it hamper your thing? You have your own space, I don’t think it matters.

Is there anything you wouldn’t do on screen?

I think you’re just playing a character. It could be immoral also. It’s a story at the end of the day. I’m open to playing grey shades and dark characters on screen. What matters is my real life, my real character…(But) I’m part of new-age movies, a flag-bearer of progressive Indian cinema. I’ll never do something regressive, which is cringe-worthy.

What has been the biggest challenge of your career?

Physically challenging was Dum Lage Ke Haisha’s climax, I had to pick up Bhumi (Pednekar) and even the body double could not pick her up (laughs). Overall, the most challenging character as an actor was in Andhadhun because it was tough to learn piano from scratch, and being a blind pianist, I could not look at the keyboard.