A third-generation Indian politician is gamifying his election campaign

WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook are nothing new to Indian politics. But now, a young third-generation politician in the northern state of Haryana has gone a step further, and completely gamified his digital campaign.

WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook are nothing new to Indian politics. But now, a young third-generation politician in the northern state of Haryana has gone a step further, and completely gamified his digital campaign.

Team Bhavya is an Android mobile app for supporters of 25-year-old Bhavya Bishnoi, who aims to nab a Congress party ticket for the first time from Hisar, Haryana, in India’s 2019 general election. Users of the app can see recent posts from his Facebook and Twitter pages, and are awarded points for liking and sharing them on those platforms. They can also share the posts on WhatsApp.

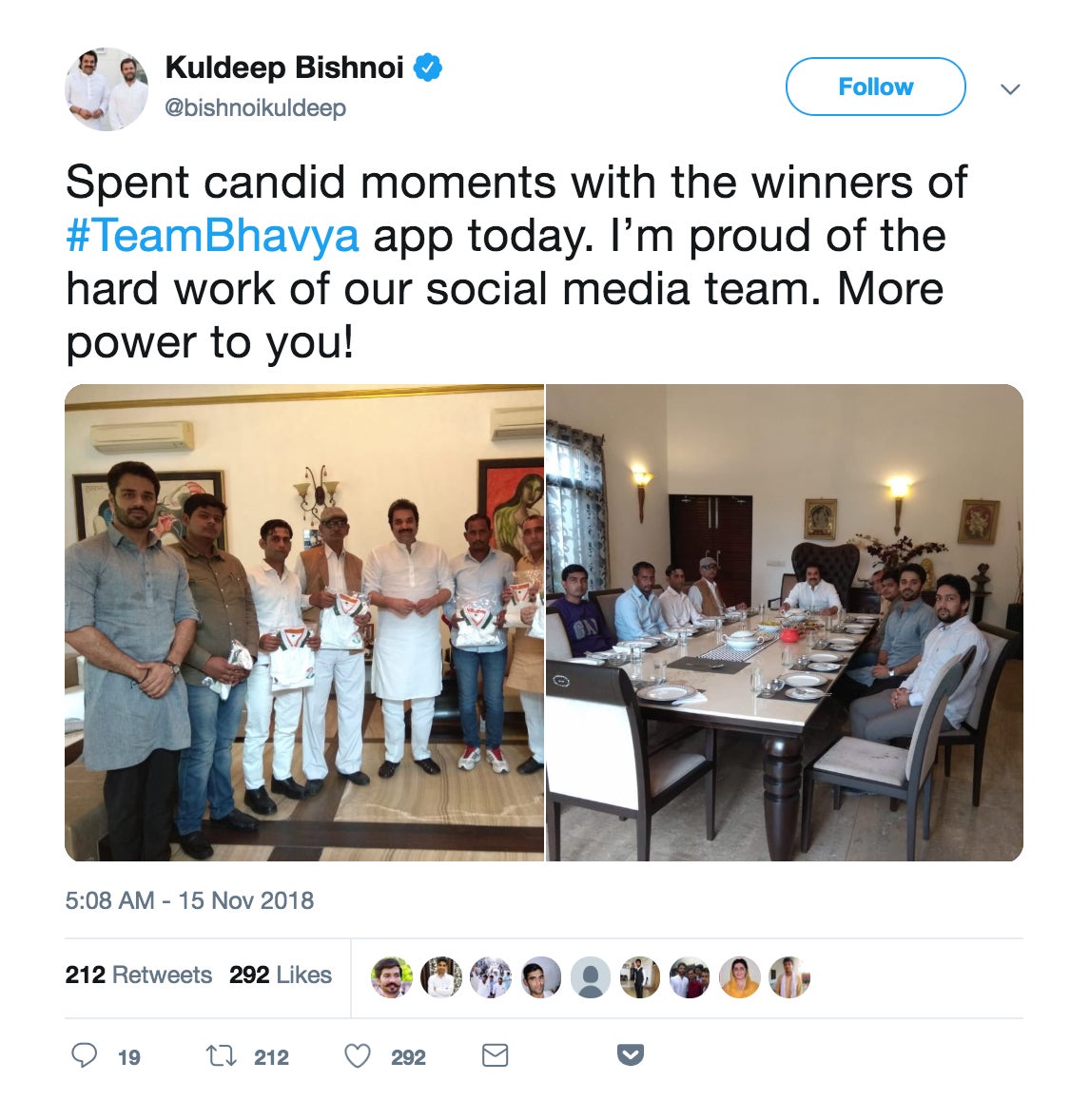

Users who score the most points are rewarded with closer access to Bishnoi and his father, the politician and former parliamentarian Kuldeep Bishnoi, whose Facebook and Twitter posts also appear in the app. (Bhavya Bishnoi comes from a political family: his grandfather, Bhajan Lal, was a three-time chief minister of Haryana, and his mother, Renuka Bishnoi, is a member of the legislative assembly in the state.)

Every month, the 10 users with the most points on the app are invited to lunch at the Bishnoi family home. The tech team that manages the app also periodically gives Bhavya Bishnoi a list of strong performers to call on the phone and thank for their efforts.

Gamification has been used in Indian politics before. For example, in the Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) campaign for the 2014 general election, NaMoNumber was an initiative that rewarded volunteers based on how many SMS-based pledges of support they could solicit from voters in their constituency.

The inspiration for Team Bhavya, however, came from outside politics. In 2016, Bishnoi helped coordinate Global Citizen, an initiative in which people could earn tickets to a concert in Mumbai by the British rock band Coldplay by performing charitable acts.

“People respond to incentives, and so I wanted to incentivise our social media volunteers to work more effectively,” Bishnoi told Quartz. “This idea had worked exceptionally well when we had set up Global Citizen India in 2016. So we developed a social media app that gamifies the entire process of social media activity.”

“Gamification really works,” said a political consultant who has worked with national parties. “You have a traditional party worker base, which are the guys who go door-to-door, the guys who’ll come to your meetings. But this really helps you to tap into a non-traditional worker base and expand your reach.”

On the day the app was launched, Bishnoi’s team saw a three-fold increase in social media activity, Shiv Dravid, CEO of ConnectHub, the company that developed and manages the app, told Quartz. The app’s initial downloads happened mostly at a large meeting of over 1,000 party workers, but Bishnoi says the downloads since then have happened more organically, with news of the app spreading by word of mouth.

The app, launched over two months ago and with around 4,000 users—of which around 1,000 are active daily—has so far helped boost Bishnoi’s social media presence. It has also helped his campaign keep closer tabs on its volunteers by analysing their digital footprints.

User experience

Many of the app’s users have been social media foot-soldiers for the Bishnois much before Team Bhavya.

Kuldeep Vats, a young engineer from Sonipat and one such long-time Bishnoi backer, said sharing party content was much more laborious earlier.

“Before, we had to go to Facebook and find Kuldeep ji’s page. Then we had to go to Bhavya ji’s page. Then we had to do the same for their different Twitter accounts,” he said. “Now, all the posts from the four profiles are in one place. You can just open the app and share everything.”

The app has made life much simpler for many of the volunteers, especially the less digitally literate ones. “To bring in other volunteers from outside the core volunteer team was hard because there was a lot of training required,” Dravid said. “That required a certain amount of in-person time and investment—and even then, you were not sure whether that person will be able to do it correctly.”

Vats was one of the app’s top 10 performers in September and October, and has had lunch twice with the Bishnois. So was Parveen Rohaj, another party volunteer from Hisar, the district where the campaign is focusing its push to gain users for the app. “Many people share content all across Haryana. It was an honour to be called for lunch with our leader out of all of them,” he said.

The key to racking up points, Vats and Rohaj said, is to check the app often. The content disappears every 48 hours in order to incentivise quick sharing. Vats estimates he spends about 15 minutes sharing posts each morning, and then periodically checks the app through the day.

The back-end

Team Bhavya has helped Bishnoi’s campaign team gain insights into who their most active volunteers are, helping them give the most dedicated ones opportunities. “You may claim you have 100,000 volunteers—but how much information you have about those volunteers is very important, because a lot of them become active for a while but then become inactive,” Dravid said.

The campaign claims that the app has also helped make volunteers more active on social media. “It holds our volunteers accountable for their work since we can track their performance through the back-end,” Bishnoi said.

Bishnoi’s team is also having certain high-performing volunteers visit others to collect information in order to “get to know our workers in a very deep way,” Dravid said. The information they gather, including data points such as occupation, native village, education, and employment status, is coupled with the digital behaviour of the app users in order to determine who is sharing what kind of content.

This, Dravid believes, will help boost the campaign’s ability to craft targeted messaging.

One immediate goal for the app is to get at least one active user per voting booth in Hisar, of which there are around 1,600.

Team Bhavya has also changed significantly since its launch, with the campaign team and its developers progressively tweaking the app according to the users’ quirks. For instance, the decision to make posts disappear after 48 hours was taken when they noticed users trying to gain points by liking many old posts.

They also recently decided to not provide points to users for sharing WhatsApp posts any more. “WhatsApp, as you see, is a completely private platform,” said Sathish Nagarajan, technology head at ConnectHub. “We do not know whether it has reached the right people or not.”

One part that isn’t likely to change, however, is the rewards system: access to the Bishnois and it’s non-monetary nature. The campaign team is trying to create a community of people who are passionate about Bishnoi’s message, Dravid said. “That doesn’t have to be commercial in nature, because when it becomes commercial in nature, it’s like a paid base. When you stop compensating, the base will go away.”

Ground results?

It is too soon to say what the actual impact of Team Bhavya will be in 2019.

The political consultant who has worked with national parties said that gamification, as previous instances have shown, “helps in getting new volunteers. It helps in people doing something to be associated with the candidates.” But, he added, as for “Whether it helps in winning elections—most probably not. It depends on the kind of constituency you’re in. In anything less than a 70%, 80% urban constituency, it probably doesn’t.”

In largely rural Hisar, it’s possible that social media’s overall impact will be limited.

Hartosh Singh Bal, political editor at The Caravan magazine, said that one potential advantage of the app could be that it would allow Bishnoi “to reach out into his own network in ways that weren’t available before. People who are tweeting out, helping him in his campaign, are not necessarily people who’ve risen through the ranks by pleasing the party.”

By the same token, Bal cautions, the app might also cause friction as “older party workers who are not digitally literate” see “upstarts taking positions they feel they’ve worked on for 10 or 15 years, just because some people are able to do social media better.”

But all this just may be part of shifting political tides. “Mostly in the parliamentary elections, you rarely see candidates who are below 40-45 (years) in age. Most of them are hardly digitally literate,” Bal said. “So I think this kind of experiment would be at the vanguard of what you’re likely to see much more of in the future.”

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.