India’s obsession with renaming cities will tear its society apart

When I began writing this column, Mughalsarai had become Deendayal Upadhyay Nagar, Allahabad had become Prayagraj, and Faizabad district had become Ayodhya.

When I began writing this column, Mughalsarai had become Deendayal Upadhyay Nagar, Allahabad had become Prayagraj, and Faizabad district had become Ayodhya.

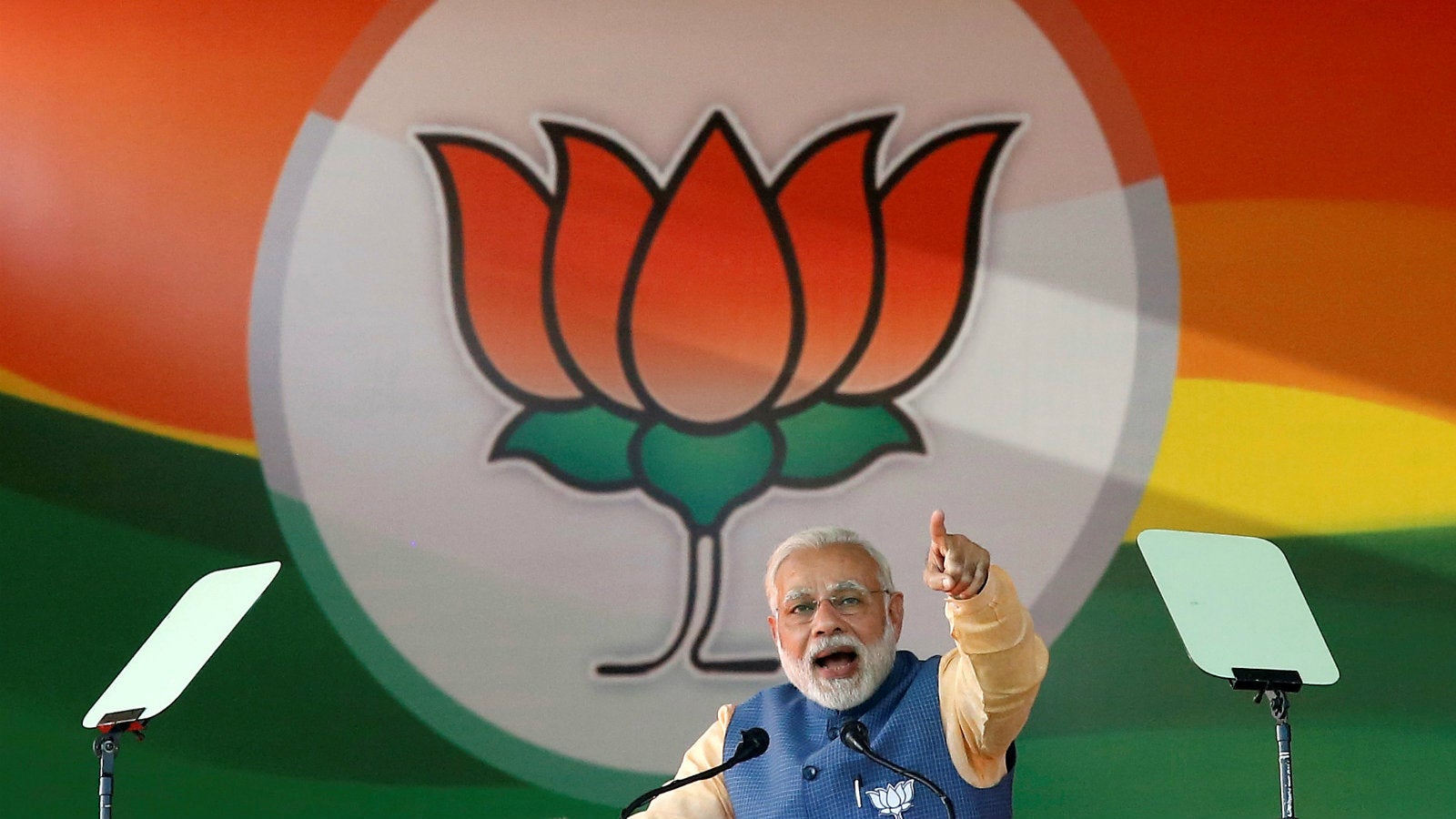

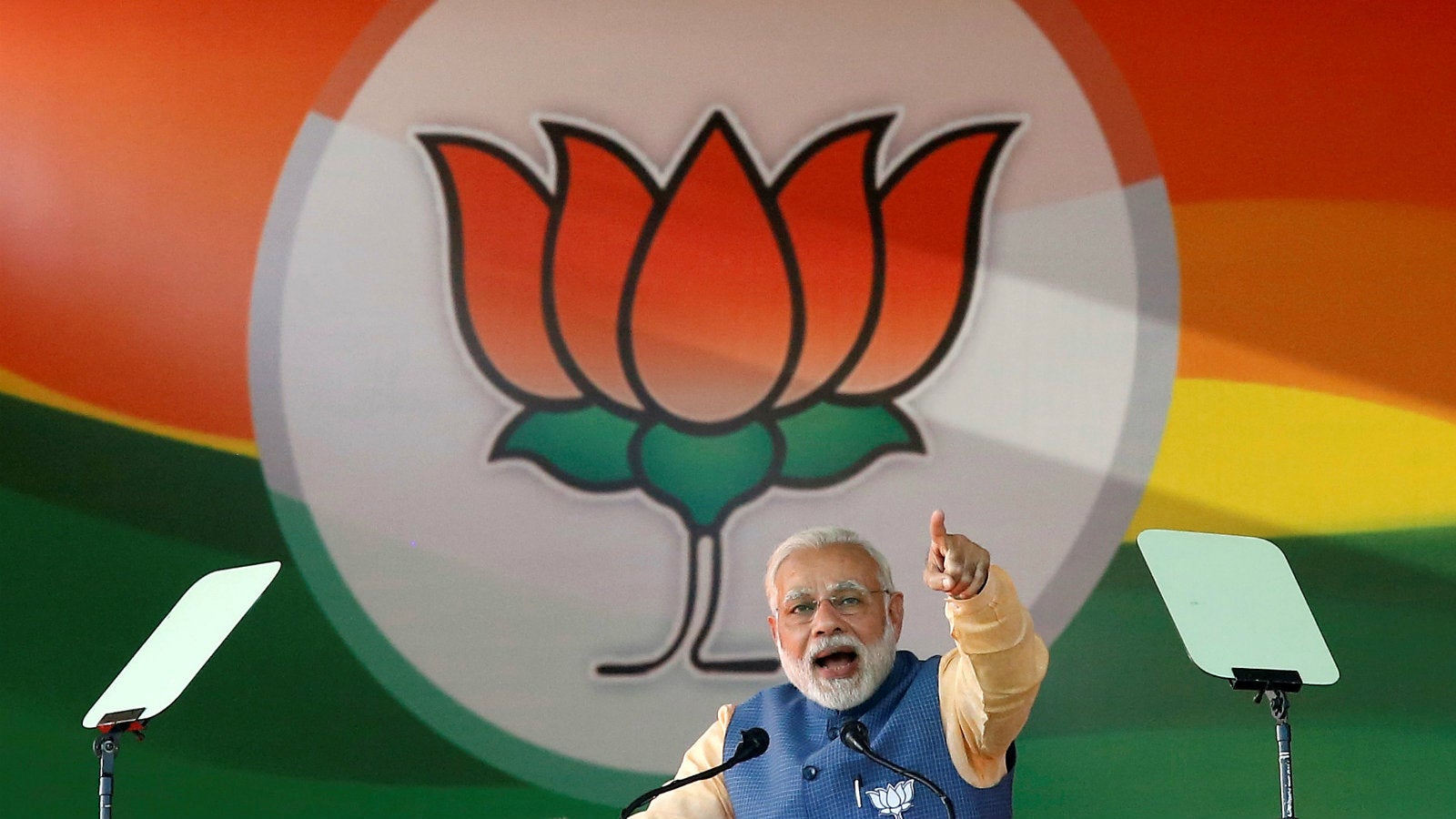

When I was still writing it, a day later, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) announced that Ahmedabad was set to become Karnavati, the Shiv Sena demanded that Osmanabad be changed to Sambhajinagar and Ahmednagar to Darashivnagar, and a BJP legislator said if his party won Telangana, Hyderabad would become Bhagyanagar.

By the time I was finishing the column, more demands, like termites pouring into a piece of weakened wood, came tumbling forth: Muzaffarnagar must become Laxmi Nagar and Agra—home to India’s biggest tourist attraction— must become, er, Agarwal, the Hindu caste.

Logic, common sense, and popular feeling play no part in this aggressive imposition of what is passed off as Hindu culture. Bhagyanagar comes from Bhagnagar, which some say was the city’s original name, given by a Muslim sultan apparently smitten by a courtesan called Bhagmati, although there is no evidence she existed.

The new names are obvious—if desperate—attempts by the Hindutva establishment to appeal to its vote bank. After renaming Allahabad or, in Hindi, Ilhabad—a city founded by the Mughal emperor Akbar and named after the syncretic faith he introduced, Din-i-Ilahi—Uttar Pradesh chief minister Yogi Adityanath said as much: “Ek achha sandesh ja sakta hai.” A good message can go out.

The message was clearly meant for the state’s and India’s majority Hindu population. Left unsaid but apparent was the messaging: we will be your party and consider or concede every claim you make, however obscure. And never mind if India’s national interests are harmed.

The bedrock of these national interests is the ability to live and work together; to compromise and cooperate; to “adjust,” as the unofficial national slogan goes. Almost every national issue—security, sanitation, economic progress—revolves around the willingness to take everyone along and ensure that no one is discriminated against because of their community and creed.

This week, the poet Ranjit Hoskote provided a much-needed reminder of this syncretic bedrock in a soaring essay on what he called “the Akbari synthesis and India’s plurality,” which explores how a Muslim emperor born in a religion that promised equality irrespective of race and class but was disdainful of other religions and philosophies wove together a nation where everyone felt they belonged.

“Akbar was hospitable to differences, even to eccentricities and idiosyncrasies, and offered them his protection,” Hoskote writes. “He had a bewilderment of Chughtais, Balkhis, Rajputs, Brahmins, Iranis, Turanis, Zoroastrians, Kayasthas, Jains, Jesuits, and numerous other groups to work with. That he knit these soloists into a memorable and reasonably enduring concert, anticipating the Republic by four centuries, was a formidable achievement.”

It is a tribute to Akbar that the republic eventually came to be. The BJP and its Hindutva allies like to delve into history, but primarily to distort it in the name of a mythical Hindu nation. Increasingly, they discard the syncretic tendencies of Hinduism and build instead a fixed deposit of hate, and, when all else fails, hope to cash in on the interest at election time. The sudden frenzy of giving Muslim-sounding cities Hindu names accompanies a steady drumbeat of the ruling party’s demands for a Ram temple in Ayodhya and a ban on menstruating women at Kerala’s Sabarimala shrine, in defiance of the supreme court’s rulings.

Dividend of divisiveness

This militantly pro-Hindu stance has wide resonance, especially in divided north India, where radicalisation among Hindus has deep roots, as these tweets from a surgeon and a police officer indicate:

Such reactions over divisive issues, the BJP believes—and not just the BJP, a nervous, ideologically bankrupt Congress now promises its voters cow shelters—pays electoral dividends. That is why the BJP used the supreme court’s order allowing women of menstruating age to enter Sabarimala as an opportunity to get a foothold in a state that has consistently rejected the party. “Everyone followed the agenda we had put forward,” Kerala BJP chief PS Sreedharan Pillai was heard saying in a leaked audio. “One after another, everyone exited the scene after surrendering before us.”

There is little doubt that the BJP and its chief campaigner, Narendra Modi, are unlikely to repeat the electoral sweep of 2014. While Modi remains the leading choice for prime minister, his aura has considerably dimmed and the party’s vote shares appear to be falling.

The BJP’s dimming electoral prospects are linked to a stuttering economy, joblessness, overblown promises—a Modi lookalike has joined the Congress, saying people who once loved him are now abusing him, asking where are Achhe Din, or good times, the ruling party’s 2014 slogan—and the crippling blow struck two years ago by demonetisation.

Demonetisation is a particular example of the willingness that Modi and his party have shown to act against national interests. Despite the advice of the Reserve Bank of India that “black money” and counterfeit notes were no justification for demonetisation—the central bank’s directors, however, said the move was “commendable,” as the Indian Express reported this week—Modi used exactly those words to justify his step into anarchy. Hailed by his supporters, including eminent economists, as a masterstroke, demonetisation crippled the economy, led to a few hundred deaths, and threw millions of people out of work, especially in the informal sector and on farms. Many of those jobs never returned.

So, Modi and the BJP have abandoned the promise of Sabka Saath, Sabka Vikas—solidarity with everyone, progress for everyone—and returned firmly to the issue that first brought them to national attention and power, from two Lok Sabha seats in 1984 to 282 in 2014: religion.

The dangers of playing with religious fire in India are apparent in Assam, one of the country’s most diverse states, where a tenuous peace has been disrupted by the BJP’s impossible promise to deport millions of illegal immigrants (which the Assamese enthusiastically believed) and its attempts to fast-track citizenship for non-Muslim immigrants (which the Assamese, as hostile to Bengalis or Bangladeshis, Hindu or not, virulently reject).

It isn’t clear if the BJP will succeed in its attempt to further cash in its dividend of divisiveness, communalise politics, and whip up Hindu sentiments, which appear to be subject to the law of diminishing returns. The desire for peace is strong and in a nation beset with problems greater than Muslim-sounding names of ramshackle towns and cities, there are greater concerns.

What is clear is that by bringing short-term Hindu interests to the forefront of public discourse and the electoral race for 2019, the BJP risks tearing apart India’s syncretic fabric and, in so doing, the national interests of the ancient country whose glories its leaders claim to celebrate.

This piece was first published on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].