Elections: The reason why the poor haven’t abandoned Indian democracy

The paradox of the coexistence of democracy and mass poverty is deeper in India than in many other societies. Some of the common reasons why democracies do not care for their poor do not hold true for India.

The paradox of the coexistence of democracy and mass poverty is deeper in India than in many other societies. Some of the common reasons why democracies do not care for their poor do not hold true for India.

First of all, the institutional design of Indian democracy (parliamentary system, asymmetrical federalism, flexible Constitution amendment) is not “demos-constraining” in that it does not put significant obstacles to the democratic popular will. There are not too many veto points that might account for the failure of floor-securing social policies to be legislated and implemented.

Second, the party system is intensely competitive with very high electoral volatility. The first-past-the-post system accentuates the effect of voters’ volatility into dramatic change in seats and government formation. Though the level of volatility has come down in this decade as compared to the previous one, a ruling party in an Indian state has just about a 50% chance of coming back to power. Parties cannot afford to be complacent and overlook issues that might concern a significant proportion of population.

Third, the state capacity in India is higher than most comparable poor countries; it still commands the force to impose its will and is not crippled by absence of resources to meet some of its key projects. All this makes it even more intriguing that the ruling parties/coalitions should not (be able to) muster adequate political will to carry out anti-poverty policies.

Finally, what makes it truly intriguing is that the poor have not opted out of democratic politics in India, at least not from routine participation in electoral politics.

…

Why elections have gained primacy in Indian democracy

Across countries in terms of the impact of the electoral system, the structure of political choices offered by the party system, the social basis of political preferences, agenda-setting and public opinion formation, the invisible role of issues and ideologies, interests and identities are seen to be the keys to making sense of elections.

Yet we simply assume that elections perform the same role everywhere. The end result of this similarity is that the experience of electoral politics in societies like India is interpreted in the light of the narrow historical experience of Western Europe and North America.

Hence the need to understand the distinctiveness of the Indian experience of elections.

One of the first things that strikes any observer of Indian elections is their centrality in India’s political life. Banners, posters, and crowds fill the streets; massive processions and rallies are a norm; the media is full of election news and every street corner is buzzing with political gossip. Though on a steady decline of late, this kind of visibility in Indian elections symbolises the pivotal role elections have come to play in Indian politics.

If tension between pre-existing social form and borrowed legal-political structure provides the basic frame for understanding Indian democracy, the history of Indian politics is an attempt by millions of ordinary people to write their own political agenda in an alien script.

An encounter such as this, if it is to lead to meaningful outcomes, requires bridges or hinges that connect the two different worlds.

The institution of elections came to perform this crucial role in India. It became the hinge that connected the existing social dynamics to the new political structures of liberal democracy, allowing for reciprocal influence. An election is often the site for a fusion of popular beliefs and political practices with high institutions of governance.

Thus an election is an occasion for the transfer of energy and resources from the “unorganised” to the “organised” sector of democracy. This is the moment when the legal-constitutional order of liberal democracy makes contact with the messy social and political reality of India. The “formal” sector is highly visible, it leads a legal-constitutional existence, it involves “civil society” groups and NGOs or a certain segment of political parties, it speaks a familiar modern language, mobilises secular identities and is easy to incorporate into a global register of democracy, even if it draws modest energy and participation.

Every political actor is aware of another “informal” sector, often seen as a source of embarrassment. Political organisations and movements that inhibit this sector speak a homespun hybrid language and fall back upon identity-based mobilisation. Though political practices in this sector lead an invisible, often paralegal, existence below the radar, this sector remains the most happening political site in terms of popular mobilisation and energy. The chasm that separates the two worlds and the absence or non-functioning of the other possible bridges has resulted in the unusual salience of the institution of elections.

This unique role is what accounts for the continued dynamism of the electoral process in India, while a number of other imported institutions and processes are floundering.

A festival of collective identity

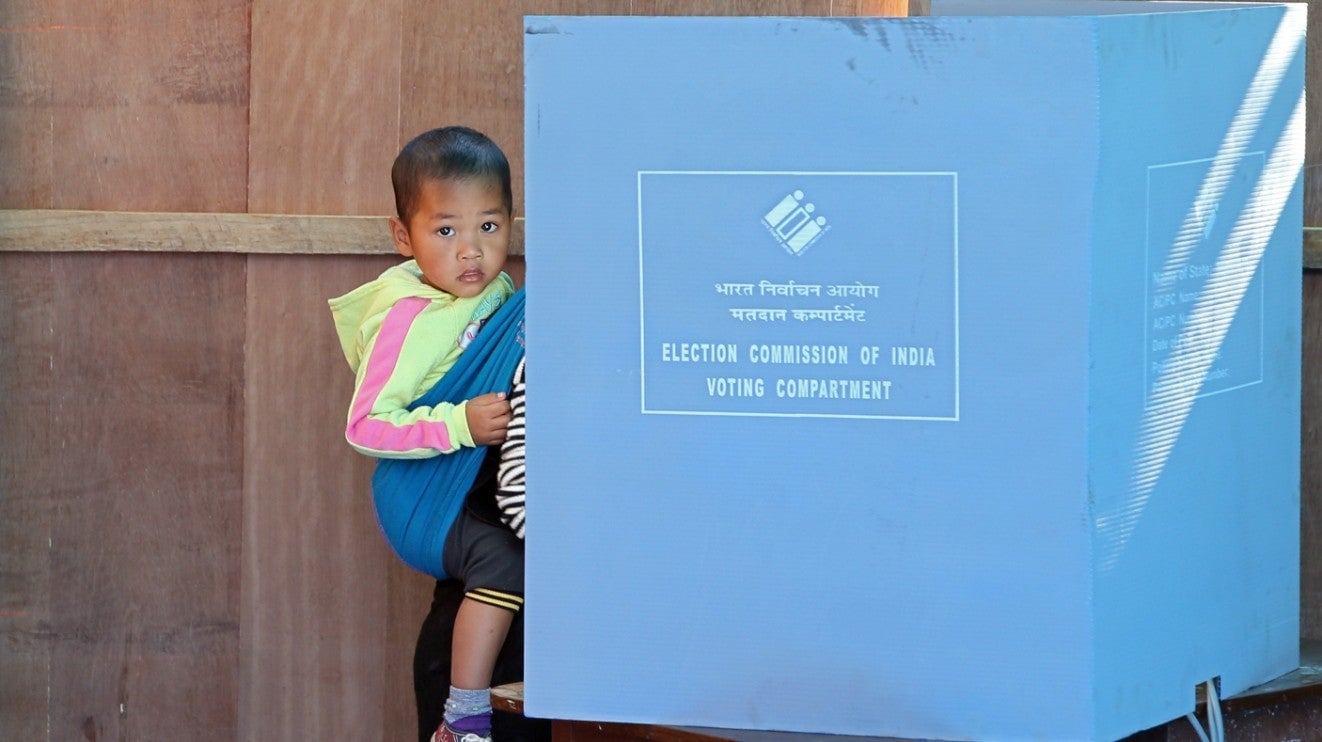

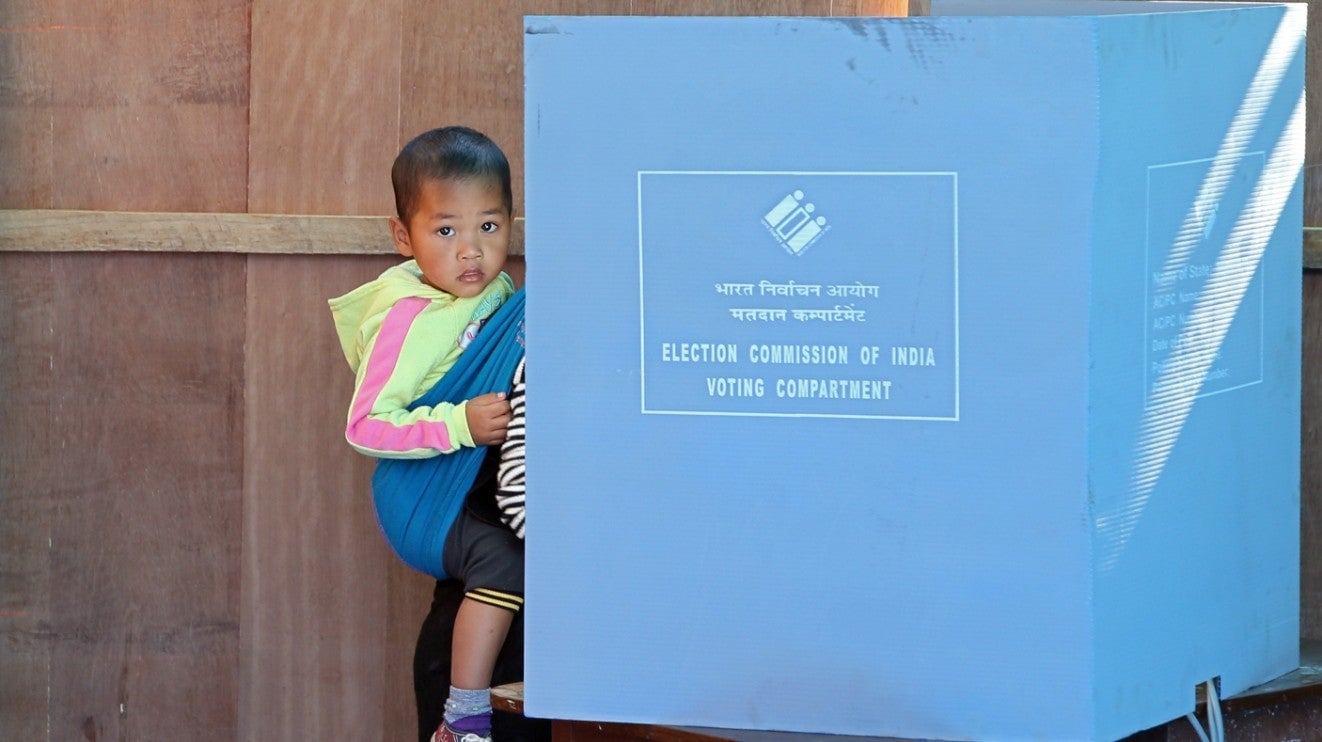

Elections in India perform many more functions. For a postcolonial country like India, successful elections are still a symbol of a national political community, something of a festival of collective identity. For the poor and the marginalised, who are excluded from the normal functioning of the state, elections are an affirmation of their citizenship and are seen as a sacred ritual of political equality. Notwithstanding a robust media that routinely uses public opinion polls, elections are still the principal site for the dissemination of political ideas and information and also the only reliable method to gauge public opinion on the big issues facing the country.

Elections force political parties to consider ideas, interests, and entities that do not lend themselves to easy aggregation through instrumentalities of the “organised” sector. Thus, elections often appear as the only bridge between the people and power, as the only reality check in the political system.

Elections are also an occasion for settling, unsettling or resettling local equations of social dominance and the arena of struggles for social identity and dignity. Elections are a site for contestation for social dominance in a locality, leading to assertion by dominant social groups and protests by subaltern groups.

Attempts by clever political entrepreneurs to manufacture a social majority often involve building a local coalition of castes and communities. This often leads to an invention of community boundaries and sometimes the jerrymandering of settled boundaries. In a micro as well as macro setting, elections are an occasion for distribution and redistribution of resources. This is the time for patronage distribution as well as the occasion for the ordinary citizens to collect their “dues” from the political class.

All this accounts for the festival-like character of the Indian elections and the fierceness with which they are contested here. At the same time, this compression of multiple decisions into a single act also results in an under-emphasis on the representational functions of elections.

Excerpted with permission from The Great March of Democracy, edited by SY Qureshi and published by Penguin Random House India. We welcome your comments at [email protected].