When pioneering aviators made eventful pitstops in Allahabad and Karachi

The film Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines revolves around an air race in 1910, and the intense, at times hilarious, rivalry between the participants. Directed by the British filmmaker Ken Annakin, the multi-starrer featured an international cast playing aviators who represent in a humorous, albeit stereotypical way, their respective nations. Every contestant in the race is desperate to claim the £10,000 prize: some attempt it with subterfuge and deceit, others with passion and heroism. Released in 1965, the film was an accurate depiction of the early days of aviation, when nations competed fiercely in the skies and Britain hungrily desired to be the leading aviation power.

The film Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines revolves around an air race in 1910, and the intense, at times hilarious, rivalry between the participants. Directed by the British filmmaker Ken Annakin, the multi-starrer featured an international cast playing aviators who represent in a humorous, albeit stereotypical way, their respective nations. Every contestant in the race is desperate to claim the £10,000 prize: some attempt it with subterfuge and deceit, others with passion and heroism. Released in 1965, the film was an accurate depiction of the early days of aviation, when nations competed fiercely in the skies and Britain hungrily desired to be the leading aviation power.

The aviation industry had been taking gradual strides since the first manned, heavier-than-air flight piloted by Orville and Wilbur Wright in 1903. From 1909 till before the Second World War–known as the “golden era of air racing”–aviators chased records, seeking glory for themselves and their nations. And much like in Those Magnificent Men in Their Flying Machines, one race captured the zeitgeist: the MacRobertson Air Race of 1934, one of the most ambitious, detailed, and extensive aviation contests.

The long-haul race featured some of the Western world’s pioneering aviators–both men and women. It was spread across, as the advertisements noted, “nineteen countries, and seven seas,” a distance of approximately 18,100 km. It began from Mildenhall airfield in Suffolk (East England) and ended in Melbourne in South Australia, the city whose centennial the race was intended to mark. One of the compulsory stops was the Indian city of Allahabad, which was the scene of some intense drama, involving both aircrafts and individuals.

The idea for the race was proposed in 1930 by Melbourne’s Lord Mayor, Harold Smith. It was sponsored by Macpherson Robertson, the founder of the popular Australian confectionery company MacRobertson’s, famous for its Freddy Frogs and Cherry Ripe brand of candies. Robertson was no novice to the field–he had sponsored similar adventures earlier and was clear in his demands. The race was to be named after the company, and there was to be no compromise on safety.

Matter of prestige

In the years before the MacRobertson Air Race, there had been similar endeavours of shorter distances, but with great prestige attached to them. These included the King’s Cup Race, instituted in England to showcase advances in light aviation; the Schneider Trophy in France, during which pilots displayed their acrobatic skills; and the Schlesinger race from South England to South Africa. In 1932, the Aga Khan Trophy was awarded to the quickest flight either way from Karachi to London. Aspi Engineer, flying from London to Karachi, narrowly beat JRD Tata flying the other way around. Engineer later served as the chief of the Indian Air Force from 1960 to 1964.

The MacRobertson Air Race, besides marking an anniversary, was a chance for airline companies such as Boeing, Lockheed, and De Havilland to showcase the growing potential of long-distance aviation, and parade their new machines, especially the rotary-winged aircrafts, which were lighter and technically more advanced than the older dirigibles and airships.

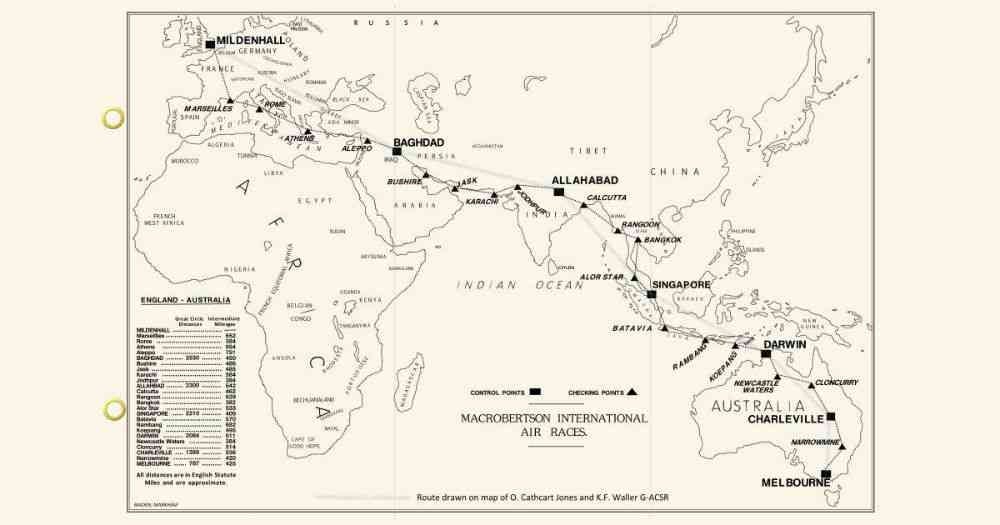

For aviators, it was yet another opportunity to face off against familiar foes. The route, complete with its five compulsory stops–Baghdad, Allahabad, Singapore, Darwin and Charleville (in New South Wales)–followed the one set by glamorous British pilot Jim Mollison in 1931. He had flown the distance as a test route–from Wyndham in Western Australia to Lympne in South England–in eight days and 19 hours. Mollison’s feat broke an earlier record, and now aviators like Sir Kingsford Smith and CWA Scott were keen to challenge Mollison and win the MacRobertson Air Race.

Open to all

Among the 63 aviators who registered for the race, VL Chandiramani from Karachi was the lone Indian entrant. But ultimately his pilot AM Murad chose not to fly and instead joined a railway company. There were other withdrawals and by October 20, the date of take-off, only 20 planes were left in the fray.

The race was set in historically interesting times. The participants, who came mainly from the US and Britain, Australia, New Zealand and the Netherlands, and the route itself were meant to show how Britain–the metropole and its colonies–enjoyed a powerful presence in those regions. But this didn’t stop other countries from surreptitiously continuing with their aviation experiments. Germany, despite the restrictions imposed by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 that disallowed it from making machines for military use, found a way out by making “dual purpose” aircraft–machines that could be quickly altered to become war planes. And in Josef Stalin’s Soviet Union, aviation researchers and pilots were preparing themselves for the first flight across the North Pole from the USSR to the Americas–one that would be successful in 1937.

The race was thrown open to virtually anyone, provided the air-worthiness of their aircraft was satisfactorily proved. Besides the speed race, there was a “handicap race” that allowed stoppages–apart from the compulsory five–at several places, such as Rome, Athens, Aleppo, Karachi, Calcutta, Jodhpur, Rangoon, and Bambang in the Philippines.

Though Allahabad was described in a race advertisement as near the “jungles of northwest India,” it was already on the aviation map. In 1911, Henri Pequet had officially carried airmail for the first time, covering the five-mile distance from Allahabad to Naini in his biplane in around 13 minutes.

Top contenders

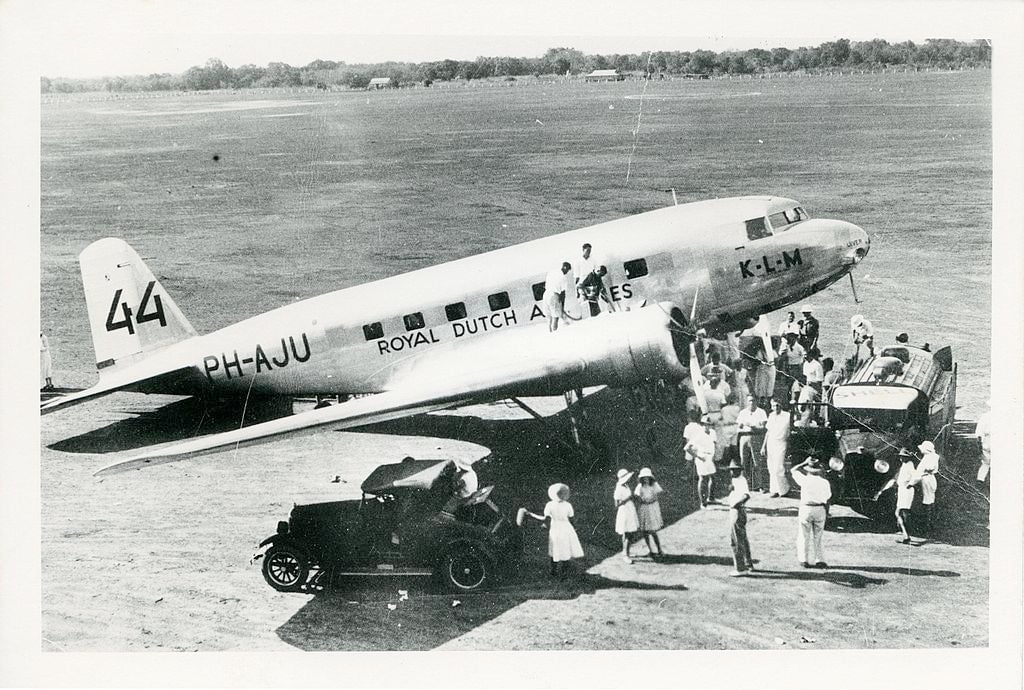

Among the favourites to win the Air Race was the husband-wife duo of Mollison and Amy Johnson, popularly referred to as the “the flying sweethearts” for their mutual love of flying, and fondness for breaking each other’s records. The American acrobatic aviator Clyde “Upside-Down” Pangborn teamed up with Roscoe Turner, who was renowned for having flown across the US twice. Mollison’s rival Scott was flying with Tom Campbell-Black. Another formidable team was the pair of KD Parmentier and JJ Moll, both pilots for Koninklijke Luchtvaart Maatschappij, or KLM, the official Dutch airlines.

Apart from Johnson, there were three women aviators, all American. They were Jaqueline Cochrane, whose cosmetic business tied in nicely with her love for flying, Laura Ingalls, who was later imprisoned as a Nazi sympathiser, and Ruth Nichols, who, like her near contemporary Amelia Earhart, broke several aviation records.

Stories from the race are now part of legend. There was an early tragedy when a plane with two British aviators perished after catching fire in Rome. The Mollisons were the first to reach Baghdad and then Karachi, setting a new England-to-Karachi record in the process. But British pilots Scott and Campbell-Blacksoon stole a lead after the Mollisons ran into trouble at Karachi, an airport where night-landing facilities were non-existent at the time. Resultant landing gear issues compelled a sudden landing at Jabalpur, where the Mollisons fuelled up with petrol from a local transportation company. This irreparably damaged their engine, prompting them to quit the race in Allahabad.

In Allahabad too, a Dutch plane piloted by GJ Geysendorffer and DL Asjes-Pronk, which had only just returned from Calcutta after repairs, caught fire after it inadvertently crashed into an ambulance, as the pilots were attempting to take off at night. The two pilots as well as several people on the ground sustained burns.

Even the last leg of the race had its own remarkable adventures that put a small Australian town in the limelight.

The Dutch aircraft of Parmentier and Moll lost its way in a storm. The sound of their airplane called Uiver, or stork in Dutch, alerted Alf Waugh, the mayor of Albury, a town in central New South Wales. He had the operator in the town’s power station flash streetlights to spell out the town’s name in Morse code. The Australian Broadcasting Corporation in Melbourne interrupted its regular schedule to request Albury’s residents to beam their car headlights on to a racecourse. All these attempts allowed the plane to land safely in the storm. The next morning, the residents tied ropes to the craft’s landing gear and pulled it out of mud.

On October 23, 1934, Scott and Campbell-Black were the first to reach Melbourne, officially completing the race in 70 hours, 54 minutes and 18 seconds. The Uiver came second, narrowly beating Turner and Pangborn, who had damaged an engine while flying from Singapore to Australia.

The race, the longest of its kind, retains a somewhat unique place in aviation history. Poignantly, many of the competitors met a tragic end. A divorced Johnson worked in Britain’s auxiliary forces during the War, and drowned in the Thames when her parachute malfunctioned. Mollison died of alcoholism. During the War, Dutch pilot Parmentier acquitted himself heroically when, as a pilot of a British passenger airplane, he landed the craft safely in London despite heavy bombarding by the German Luftwaffe. Parmentier, who was later an aviation instructor, died in a freak accident when his craft crashed into a power line. Scott committed suicide in 1946.

As for the planes, only one–the Boeing 247-7, flown by Turner and Pangborn– survived, and is preserved in the Air and Space Museum in Washington DC. The Uiver crashed in Baghdad in 1944. The De Havilland comet flown by the Mollisons was destroyed during a hangar fire in Paris in 1940. Aviation aficionados have recreated models of some of these early machines, which are on display in airplane museums across the world. The race was made into a movie in Australia in 1990, called the Great Air Race. The film focuses on the few aviators who became larger-than-life figures, following their participation in the race. It evokes memories of a time when aviation technology was largely rudimentary, and aviators had to rely on their skills and instincts in their heroic bids to confront the skies.

This story originally appeared in Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].