The 91-year-old female opera artiste who has defied traditional Indian musicians

The statuesque young woman with a powerful voice who joined the cast of director Sheela Bhatia’s Heer Ranjha in 1956 was an unknown face in the theatre circles of Delhi. But for a city still fiercely nostalgic about pre-Partition Punjab, she soon became the definitive Heer.

The statuesque young woman with a powerful voice who joined the cast of director Sheela Bhatia’s Heer Ranjha in 1956 was an unknown face in the theatre circles of Delhi. But for a city still fiercely nostalgic about pre-Partition Punjab, she soon became the definitive Heer.

“O vekho, Heer ja rahi (Look, there goes Heer)–the cry would follow her around Connaught Place when she stepped out to shop. Even the taxi drivers who didn’t recognise her would praise Heer when they dropped her off at the theatre. “Othe Heer haiji. Ki gal hai, bhai wah (Wow, Heer is playing here)!” The heartiest compliment was to come from Jawaharlal Nehru: “Gazab kar diya, ladki (You are a wonder, girl).”

But Shanno Khurana, who played the tragic heroine in Waris Shah’s epic work, was anything but a drama queen. She was, and remains to this day at 91, an exceptional classical vocalist with a vast repertoire, trained by the legends of her time–Mushtaq Hussain Khan, Thakur Jaidev Singh, and SN Ratanjankar. Not only did she shine as Bhatia’s Heer, Khurana also went on to compose four landmark classical music operas through the 1960s and ’70s–Sohni Mahiwal, Jahanara, Chitralekha, and Sundari.

What Khurana did at the time was a risky proposition for a classical vocalist. Maharashtra had, since the late 18th century, a strong tradition of natya sangeet, which allowed classical music and theatre to come together. But in the more conservative North, anything lighter than a khayal was still sacrilege for a serious musician. While instrumentalists like Ravi Shankar, Chatur Lal, Ali Akbar Khan, and several others had begun experimenting with alternative systems, classical vocal music was still staunchly insular.

“Yeh to sahab opera gaati hain, inko kyon bula rahein hain (she does operas, why call her)?” Khurana recalled the snide line thrown at her when she was invited to sing at concerts. The disdain of her fraternity clearly rankled, and still does, but Khurana’s engagement with music has always been eclectic, going well beyond the performance stage. She holds a PhD in the folk music traditions of Rajasthan from Khairagarh University, and has a deep grasp of tappa, a challenging genre that combines folk music with the rigour of ragas.

“I thought: why not bring classical raag to the layman?” she said as she recalled her career as an opera composer at Art Matters, an event hosted in Delhi by the Raza Foundation. “Otherwise, the general response to classical music is: yeh kya aaaaa kya laga rakha hai (what is this aaa?).” Khurana’s operatic experiments were different from natya sangeet in that she wouldn’t allow any spoken words at all. “Even if you said yes or no, it had to be set in music,” she said.

So how did the story of Khurana and her grand classical operas begin? Sheila Bhatia of the Delhi Art Theatre, known for her Punjabi folk operas such as Dard Aayega Dabe Paon and Sulagda Darya, was looking for a singing Heer in the mid-1950s. “Aa toh sahi (come and see),” she told Khurana.

But once she stepped into the opera, which was packed with folk tunes, Khurana found to her horror that while the cast could sing, they had no clue about notes, scale or pitch – everyone simply stood up on stage and let rip.

“Most singers had no idea where to start or end,” she recalled. “My ears couldn’t take it. Hali, who played Kazi, would suddenly go besura (off-key) in the middle of the doli scene and it would completely throw me. So I sat with conductor Susheel Dasgupta and made sure everyone could work in tune. I started training voices, making them practise by the rules of music. And the play was such a huge hit [that] all the musical flaws were overlooked.”

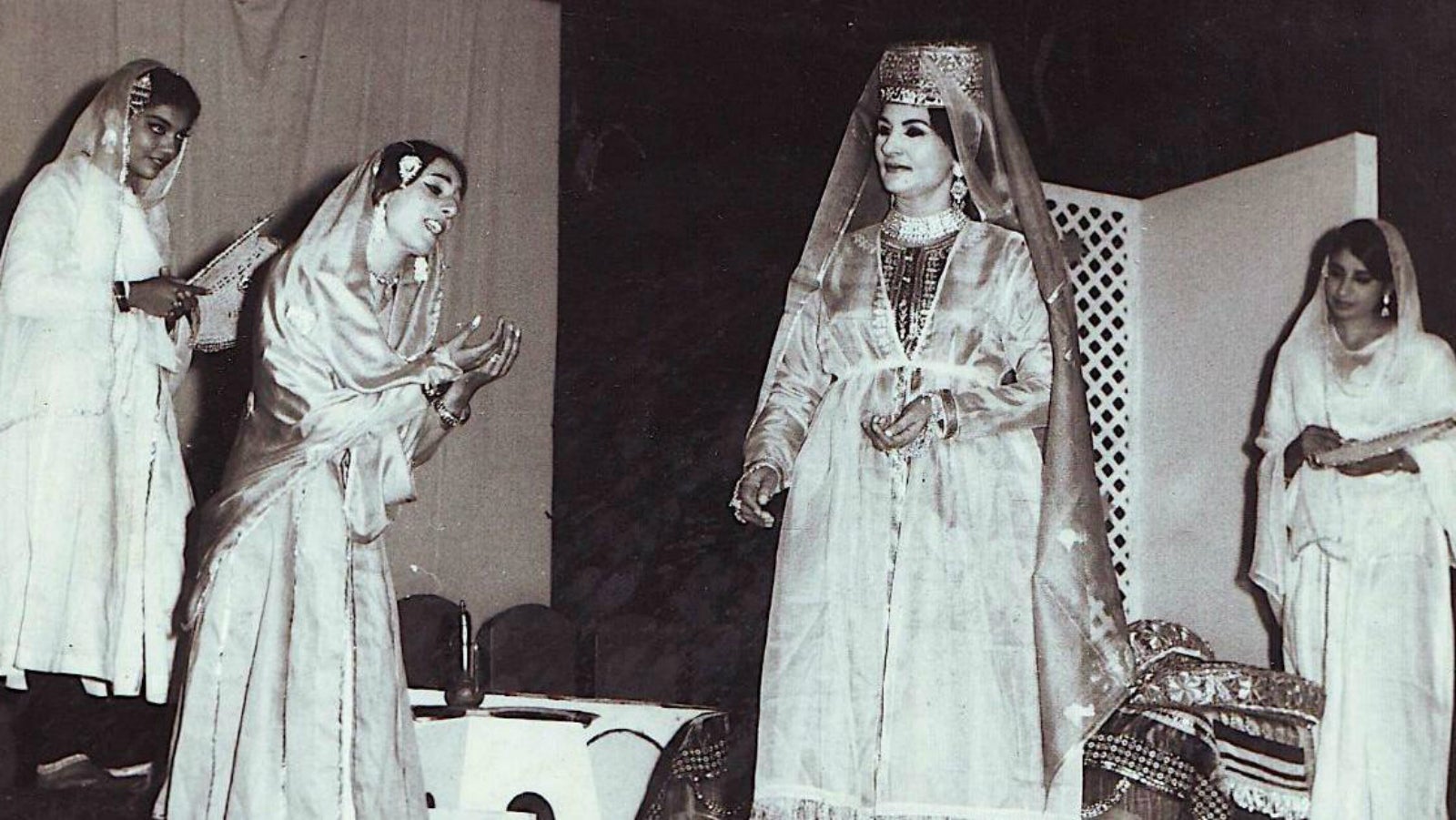

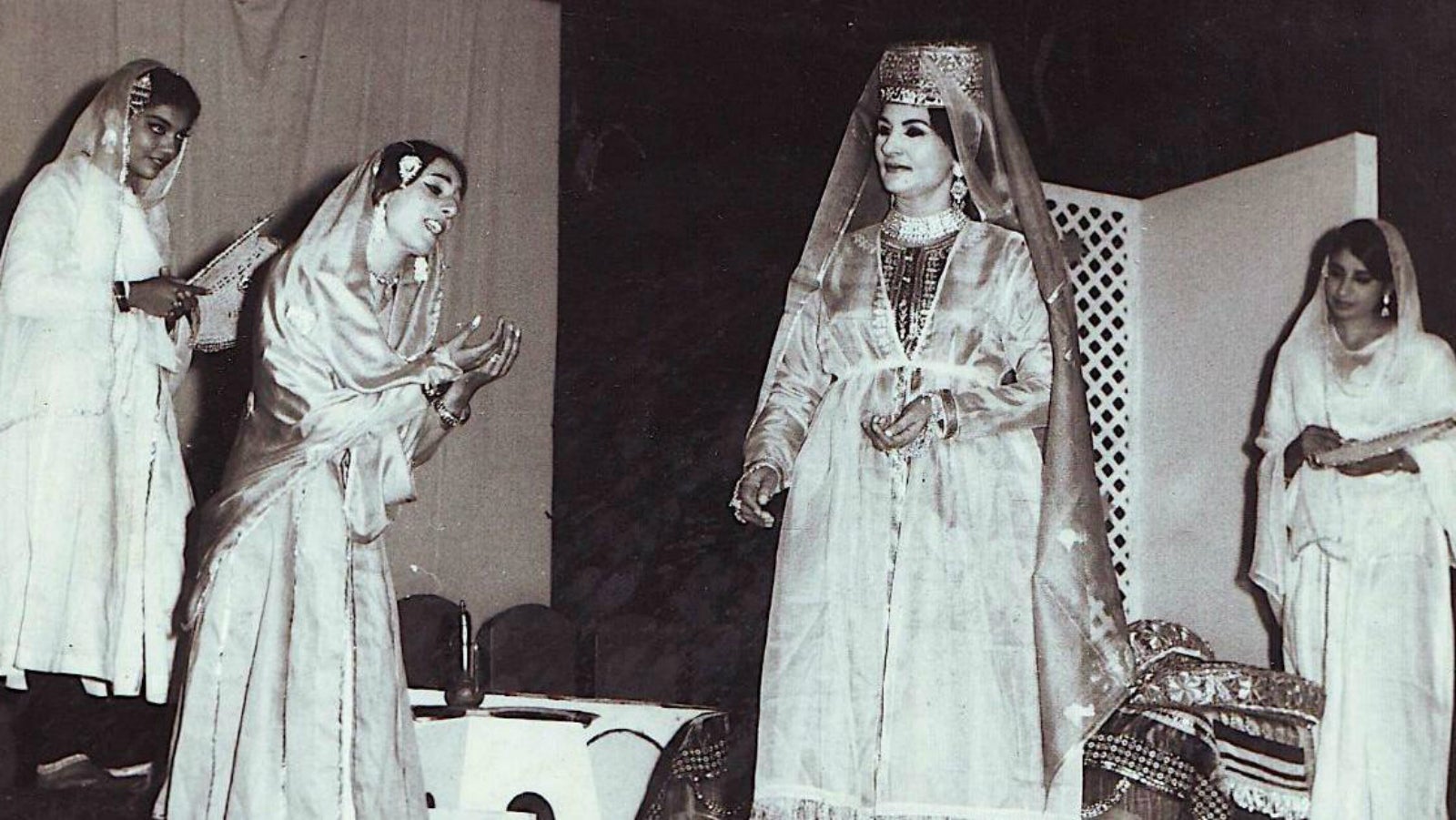

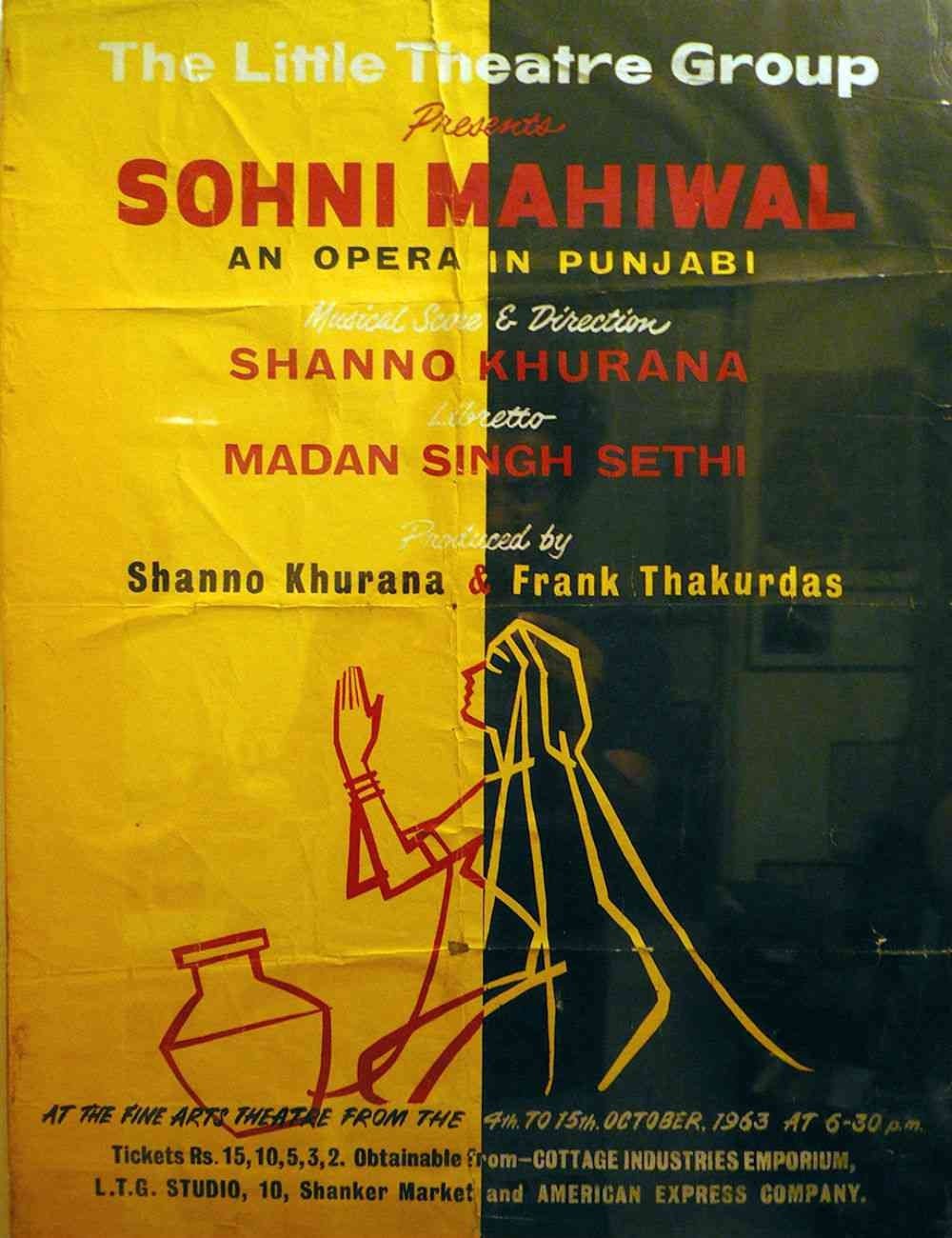

Khurana decided to put her skills to compose a fully classical opera. She began working on Sohni Mahiwal, yet another tragic love story from Punjab. She wove in as many as 40 raags into the opera. “It was like a classical western opera,” she said. “Every word, even a filler, was made musically meaningful. The words and mood dictated the raga. I brought in the concept of kaaku bhed (voice variations).”

Each raag merged into the next, this time pitch-perfect–from Hindol to Sohini, Kaafi, Ahiri Todi to Madhuvanti–to tell the story of the star-crossed lovers. “I experimented but stayed within the niyam (rule) of ragas,” she said.

But with days to go before the shows all sold out–things started to unravel. Emani Sankara Sastry, the great veena master and then head of the Carnatic vadya vrinda (orchestra) at the All India Radio (Ravi Shankar headed the Hindustani section), was to head the orchestra for the opera. But a red tape glitch meant he had to pull out 10 days before the show.

The play was now without an orchestra. Scrambling to save the situation, the team scoured the city and found a sitarist, a sarangi player and a tabla player, and somehow scraped together a team of 10 instrumentalists. “We started from scratch, so we had to work 12 hours a day on the score,” said Khurana. “[In the] middle of the night, if I had a sudden musical idea, I would wake up and note it down, even as my husband snored by my side.”

Then every vocalist’s worst nightmare came true. Khurana, who was playing Sohni, lost her voice five days before the play debuted. “I was asked to shut myself in a room, medicated, and not allowed to talk for five days,” she said. “Then I went on stage…and sang. I don’t know how the miracle happened.”

Sohni Mahiwal was a huge success – it was watched by everyone from Nehru and Dr Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan to theatre legend Ebrahim Alkazi. “Sohini Mahiwal dekhne seedha Doon se aa raha hoon (I am coming from Dehradun to watch you),” Nehru raved.

Her operas also pulled in the rising stars of theatre at the time. The likes of BV Karanth, Prema Karanth, Roshan Alkazi, and BM Shah joined her later works. Artist Satish Gujral designed the posters and his wife Kiran Gujral the costumes.

But Sohni Mahiwal’s success also brought about the end of its great run. Its libretto writer sought a stay order on the performance of the opera, claiming copyright over its content. And with all the money invested in the play, the sets and costumes were lost.

The next time, Khurana was smarter. In 1969, she floated an organisation called Geetika to produce the operas, and started work on an Urdu epic, Jahanara, with librettos scripted by writer Rifat Sarosh.

“None of us knew Urdu,” she said. “We wrote the lyrics in Devanagri [and] got a masterji to come in twice a week to teach us tallafuz (articulation) for a year.” This opera had 60 raag-based songs, and an aria composed for the episode marking Jahanara’s birthday. Dil mustareeb hai mai kya karun/Aankhen hain bekhab main kya karun, for instance, would start with Jaijaiwanti, go on to Yaman and then dovetail into Shivaranjani, Bhairavi and Madhuvanti as the story progressed.

Khurana was lucky enough to rope in BV Karanth as producer. A musically sound theatre director, he had been taught vocal music by Gwalior gharana giant Pandit Omkarnath Thakur. “He was a systematic, quiet worker, [and] each scene had [a] diagram to it,” said Khurana. “His wife Prema, advised by Roshan [Alkazi], did the costumes, again drawing each costume separately. BM Shah worked the sets.”

The play was so much in demand that it went across the country. The entire troupe–from the carpenter on the set to the director – travelled together in buses and trains. With not much coordination, these travels were like adventures–at some venues the troupe would find the theatre shut and then a desperate search would begin for a new location. “But people were generous, they would feed us, find us another stage,” said Khurana. “Those were different times.”

Chitralekha, Bhagwati Charan Verma’s 1934 epic novel set in Mauryan times about a rebellious courtesan and the battle between material and spiritual world, had already yielded two films by the time Khurana started work on it in 1974 (this was 11 years after the release of the Meena Kumari starrer of the same name with a brilliant score by Roshan). With librettos by Bal Sarup Rahi, the opera – with the talented Karanths still a part of the crew – turned out so well that a teary-eyed Verma went on to call it the best interpretation of his work.

Khurana’s last opera Sundari, performed in 1979, was based on an 1896 novel on Sikh valour by Punjabi litterateur Bhai Vir Singh. By this time, Khurana found that theatre was enriching her voice and singing. “I learnt the art of pukar, the calling out, that I used to hear in the voice of Allah Jillai Bai, the legendary folk singer from Rajasthan,” she said. “I would hear her voice wafting across my home in Jodhpur as a child but never realised its greatness till I started working in theatre.”

In retrospect, she says, she persisted despite every criticism. This opened up some very unconventional opportunities for her and her collaborators – she sang a Ghalib ghazal Aye taaza waaredan-e-bisat-e-hawa-e-dil for Indrani Rahman’s bharatanatyam, made kathak dancer Damyanti Joshi dance to her tappa at a festival of thumri, and got her guru’s son, Ghulam Taqi Khan, to sing a tappa for Sohni.

“Thakur Jaidev Singh used to say, ‘Why should we have to label our music?’” she said. “Where do you think our raag music grew out [of], our complicated tala system? Where did Kumar Gandharva draw inspiration from? Our rich folk music. Why should anything be out of bounds?”

This article was originally published in Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].