In Chennai, a medical-school entrance exam may decide who wins the election

It’s called NEET (acronym for “national eligibility cum entrance test”), and as voting is underway in Tamil Nadu, everyone in the streets of Chennai seems to have an opinion about it.

It’s called NEET (acronym for “national eligibility cum entrance test”), and as voting is underway in Tamil Nadu, everyone in the streets of Chennai seems to have an opinion about it.

NEET is a standardized test high school graduates are required to take to opt for medicine, regardless of their graduation marks, and it’s a hot-button ticket in the state.

The test has become the symbol of the national government’s interference in state politics, particularly in the south, and to many, it embodies a worldview and value system imposed by the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), intending to punish poor and lower-caste people.

The test was first announced in 2012, and after a legal battle, it was eventually imposed countrywide in 2017, with the BJP’s support. Administered by the central board of secondary education, the test was initially given in English and Hindi, with several other languages allowed in the answers since 2017.

Without accessible training, and poor translation of the questions into Tamil, for many students in Tamil Nadu the test became an insurmountable obstacle. The state’s school syllabus is considerably different from the one NEET is based on, and the language barrier severe, particularly for students of poorer backgrounds who cannot afford to study in English.

As a result, even excellent students have been failing NEET. This is what happened to Shanmugam Anitha, a Dalit girl of 17 who had gotten the near-perfect score of 1,176/1,200 in her high-school graduation: As the daughter of a daily wager, she didn’t have the resources to prepare for the test privately, and, unable to even comprehend most of its questions, she failed. Anitha would have been the first person from her community to become a doctor. Distraught over the results, she took on a legal battle but, unable to reverse the admission decision, she committed suicide.

Protests around the state demanded NEET be abolished. People continue to decry lack of access to affordable preparation and see the central government’s imposition of the test as a way to discriminate against the local underprivileged population, which has for many years been relying on education as an effective means of social promotion. Tamil, with one of the highest literacy rates in the country, owes a vibrant educational system to its deeply Dravidian politics.

Unlike the rest of the country, the Congress and BJP barely matter in the state, which is instead typically disputed between the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (DMK), currently a Congress ally, and the All India Anna Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam (AIADMK), on the side of the BJP. The two parties share a root in the Dravidar Kazhagam, a movement founded at the time of independence to eradicate the caste system, and abolish a Brahamin-led power structure in favor of equality. Though it subsequently abandoned the goal, the movement aimed to create a Dravidian state independent of northern India, uniting the native speakers of Dravidian languages like Malayalam, Kannada, Telugu, and Tulu, apart from Tamil itself, as a way to empower people in southern India who sought to counter the dominance of the northern Indian states, often perceived as descendants of the Aryan race.

Tamilians are proud of their education, and the NEET issue struck a chord with people across social backgrounds. Parties and independent candidates all have a clear position on it, with the AIADMK supporting the exam, while most others, including the DMK, opposing it.

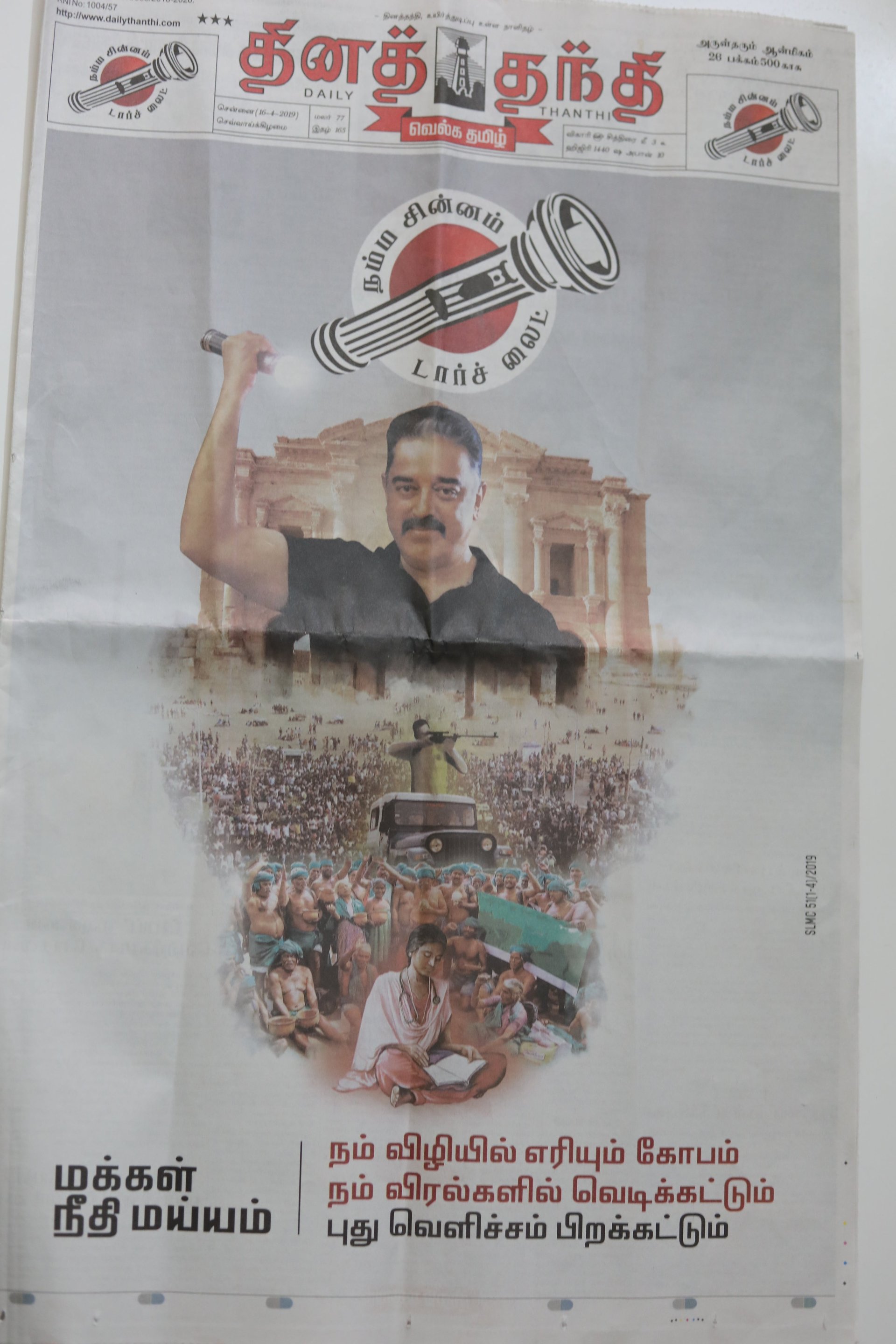

Kamal Haasan, a renowned actor and founder of the Makkal Needhi Maiam party, (contesting with the flashlight symbol) made abolishing the NEET—symbolised by Anitha’s photograph—a main issue in his front-page advertisement.

“In Tamil, you will find that the surgeon who is going to take care of you at a hospital looks like the girl next door,” explains media entrepreneur and longtime political journalist Peer Mohamed, “because she is the girl next door.” Underprivileged people, he says, are greatly aware that they can pursue a high education and improve their social standing—and traditionally, they have done so.

Speaking to people in the commercial hub of Tata Nagar in Chennai, it is hard to encounter anyone who isn’t aware of NEET, with many saying they will cast their vote keeping in mind where the parties stand with regard to it.

“Jayalalithaa (the late Tamil Nadu chief minister) built many good government medical colleges, that ‘Yogi state’ has, maybe, one,” says Senthil Kumar, a restaurant manager, referring to Uttar Pradesh (UP), whose chief minister is Yogi Adityanath (UP actually has nine medical colleges, compared to Tamil Nadu’s 24). Kumar, a long-time supporter of the AIADMK, this time plans to vote for its traditional opponent, the DMK, which has promised to get rid of NEET.

Varaja Ganapathy, a master’s graduate currently pursuing further studies, says the government should not mandate any tests until it’s ready to provide access to effective, accessible training. “Schools should implement the same syllabus everywhere,” she says, adding that standardizing the curricula would be necessary to make any test fair. She plans to vote for someone who will get rid of the test.

However, not everyone is so sold on the promise of abolishing NEET. D Azha Hari Siva Kumaran, a small-business owner, thinks the test should be scrapped, but won’t vote a party based on that: “They say they’ll scrap it, but once they’re in power they will not do it.”

Meera Maria contributed to this report.

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.