Indians who don’t like any candidate have a better choice than not voting

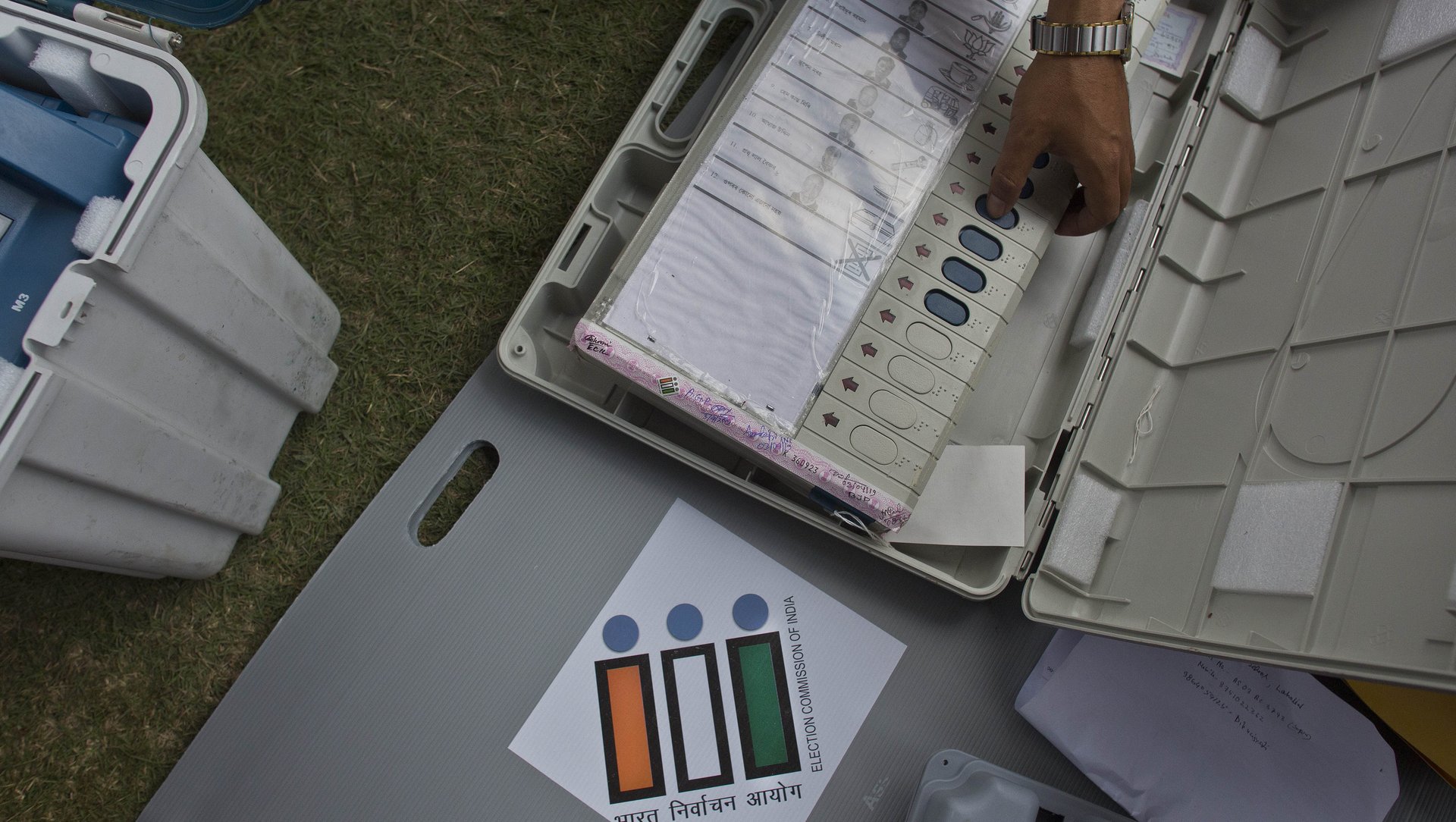

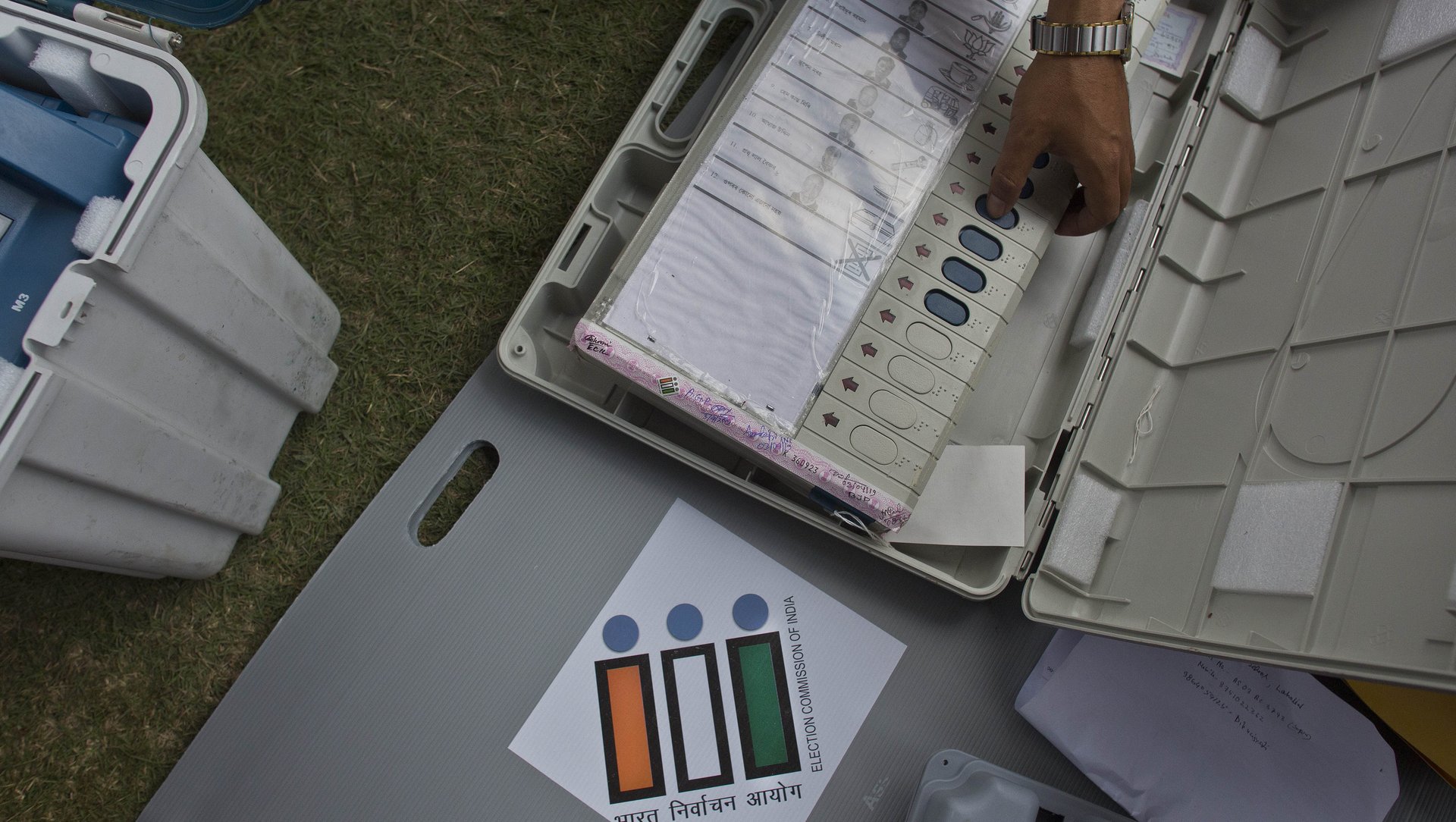

Like many voters across the world, Indians are increasingly disillusioned about politics. Unlike voters in most countries, they have an effective option to register that feeling at the polls: a button on electronic voting machines dedicated to “none of the above,” or NOTA.

Like many voters across the world, Indians are increasingly disillusioned about politics. Unlike voters in most countries, they have an effective option to register that feeling at the polls: a button on electronic voting machines dedicated to “none of the above,” or NOTA.

“I used to cross everyone out with the paper ballot,” one voter told Quartz in Wayanad, Kerala, “now I just go NOTA, NOTA, NOTA.”

The option, together with its dedicated symbol, was introduced in 2013 by a Supreme Court order in recognition of a citizen’s right not to vote and also maintain the confidentiality of that choice. With electronic balloting, voters no longer have the option to select more than one candidate or deface the ballot, therefore cancelling their vote null.

Hence the NOTA, which has since been used in the 2014 Lok Sabha elections—where it earned a respectable 1% of the votes—and in state elections since. (India isn’t the only place to have a similar option: Bangladesh does too, for instance, and so does the US state of Nevada, where voters can select “none of these candidates.”)

In several races, the NOTA option has earned more votes than any one party. In 22 seats in the Madhya Pradesh elections of 2018, NOTA totaled more than the margin of victory. NOTA cannot win the election—even if represents an absolute majority. The same Supreme Court ruling that introduced it noted that its purpose is also to “compel the political parties to nominate a sound candidate,” by showing that they failed to provide voters with candidates of high enough moral and political standing.

In Mumbai South, a constituency with a tradition of low turnout (according to the preliminary Election Commission data, 55.11% Mumbaikars voted this election, an increase over the 51.59% of 2014, but still below the national average of 65.15% so far in 2019) NOTA got 1.23% of votes in the past Lok Sabha election. In Jijamata Nagar, a slum area in Worli, in Mumbai South, many voters expressed the intention of voting NOTA, some go as far as displaying banners announcing their choice ahead of the April 29 vote.

On election day, Quartz spoke with residents of the area about the push for NOTA.

Few in the district —currently represented by Bharatiya Janata Party’s (BJP) ally Shiv Sena—felt comfortable discussing their voting choices on the record. Some cheekily raised their flat, close palm, to indicate that they had chosen Congress candidate Milind Deora.

Still, some voters offered insight as to why the option might be popular in Mumbai South.

“In five years, they have seen nothing,” said Omar Farouk, an accountant.

“No one has done any work, no one has done anything for the constituency,” said Abdul Karim, a real-estate agent who was volunteering to help people find their names in the voting rolls. “People want to tell the government these persons have not done any good, that no candidate is good.”

Jobs are on top of people’s minds, as is getting respect for all religions, notes to Ifdikhar Sarkhot, a merchant navy member from the neighborhood.

Shasheer Aman, an 80-year-old taxi driver, said some people might think voting NOTA is a way not to take sides. He thinks it better for his community, which is predominantly Muslim, to vote for Congress instead.

“They don’t take sides, they want everybody together, they want peace,” he says, “these others [Shiv Sena] don’t like Muslims.”

Read Quartz’s coverage of the 2019 Indian general election here.