Why is this Indian billionaire splurging on an Australian mine guaranteed to lose money?

By mid-June, if everything goes as expected, Adani Australia will receive the final environmental approvals for its proposed Carmichael coal mine and rail line development.

By mid-June, if everything goes as expected, Adani Australia will receive the final environmental approvals for its proposed Carmichael coal mine and rail line development.

Newspaper reports based on briefings from Adani suggest that, once the approvals are in place, the company could begin digging “within days.”

On May 31, the Queensland government approved Adani’s plan to protect a rare bird, apparently leaving it with just one final regulatory hurdle: approval for its plan to manage groundwater.

Its billboards in Brisbane read: “We can start tomorrow if we get the nod today.”

But several big obstacles remain. Even after governments are out of the way, it will have to deal with markets and companies that aren’t keen on the project.

Obstacles aplenty

First up, there’s the problem of access to Aurizon’s rail line. Adani originally planned to build its own 388km railway from the Galilee Basin to its coal terminal at Abbot Point.

However, in the scaled-down version of the project announced last year, Adani plans to build only 200km of track, before connecting to the existing Goonyella line owned by the rail freight company Aurizon.

That requires an agreement of access pricing and conditions. Aurizon is legally obliged to negotiate with Adani, but has shown itself to be in no hurry to reach a deal.

Then there’s insurance. Faced with rejection by every major bank in the world, Adani announced it would fund the project from its own resources. But now insurers, including nearly all the big European firms and Australia’s own QBE, are saying the same sort of thing as the financiers.

Without insurance, the project can’t proceed, and the pool of potential insurers is shrinking all the time.

Not particularly financial

But the most fundamental problem may lie within the Adani group itself. The $2 billion (around Rs14,000 crore) required from the project will ultimately come, in large measure, from chairman Gautam Adani’s own pocket.

With an estimated wealth of $7 billion, he can certainly afford to pay if he chooses to. But it would represent a huge bet on the long-term future of coal-fired electricity, at very bad odds.

In my analysis of the original Carmichael mine proposal in 2017, I concluded that the profit from operating the coal mine would be around A$15 (Rs724) per tonne.

A recent analysis of the revised project by David Fickling for Bloomberg yielded a marginally more favourable estimate of $16 per tonne, or $160 million a year for the initial output of 10 million tonnes a year.

That’s a small return on A$2 billion, before considering overheads and depreciation.

It’d need a long life

Such an investment could only be profitable on the basis of a mine with a long life and substantial potential for future expansion. How likely is that? When the start of construction was re-announced last November, it was suggested the coal might be shipped by 2021. With six months’ delay, and the insurance problem noted already, 2022 seems like the earliest possible date.

But by that time, the current construction pipeline for coal-fired plants in India will have been worked through, and very few new ones will be being commissioned. A mere 8 gigawatts of new coal-fired power was commissioned in 2017-18, partly offset by 3.6 GW of coal-fired power stations that closed down.

The Indian government has stated that no new coal plants will be needed after 2022, or 2027 at the latest.

…which it might not get

In these circumstances, newly opened coal mines will be able to sell coal only if they can displace existing suppliers. This suggests prices will have to fall to a level sufficient to ensure further closures of existing mines. Such a fall would erode or eliminate Adani’s already thin margins.

By 2030, with the project still in its relatively early stages, most developed countries will have stopped using coal-fired power. The others will be moving fast in that direction. So far under President Trump, the United States has closed 50 coal-fired power stations, and will almost certainly never build another.

The only glimmer of hope for coal has been in less developed countries in Asia. But over the course of this year, even these hopes have dimmed. Major banks in Japan and Singapore have withdrawn from funding new coal projects, following the lead of the global banks based in Europe and the US.

That leaves South Korea and China as potential sources of funding. Korea is already phasing out coal-fired power domestically and its banks are being pressured to divest globally. The option of relying solely on China is problematic to say the least.

To sum up, unless current trends change dramatically, the economic life of the Carmichael mine is unlikely to be more than a decade—nowhere near enough to recover a A$2 billion investment.

Explaining Adani

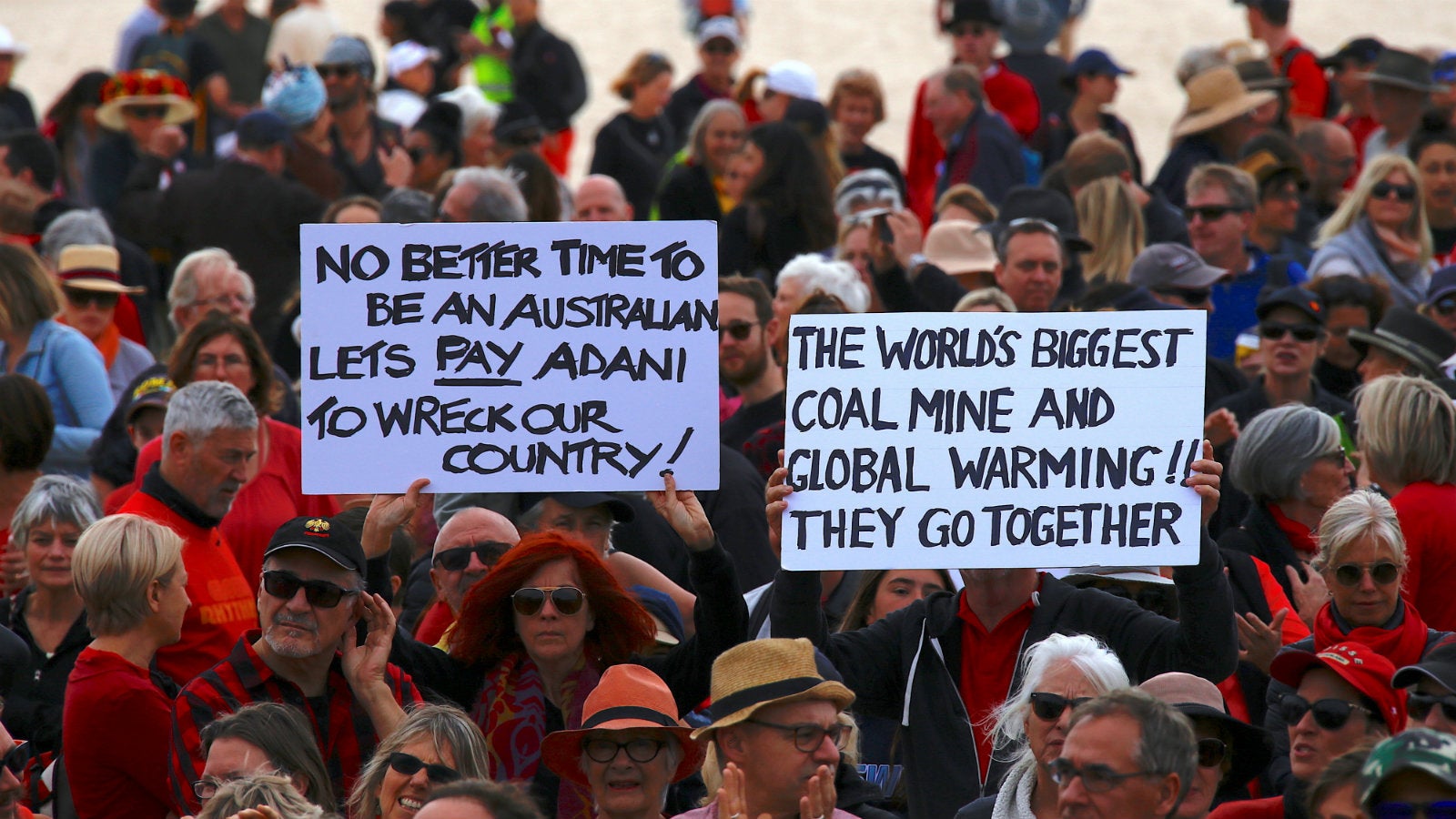

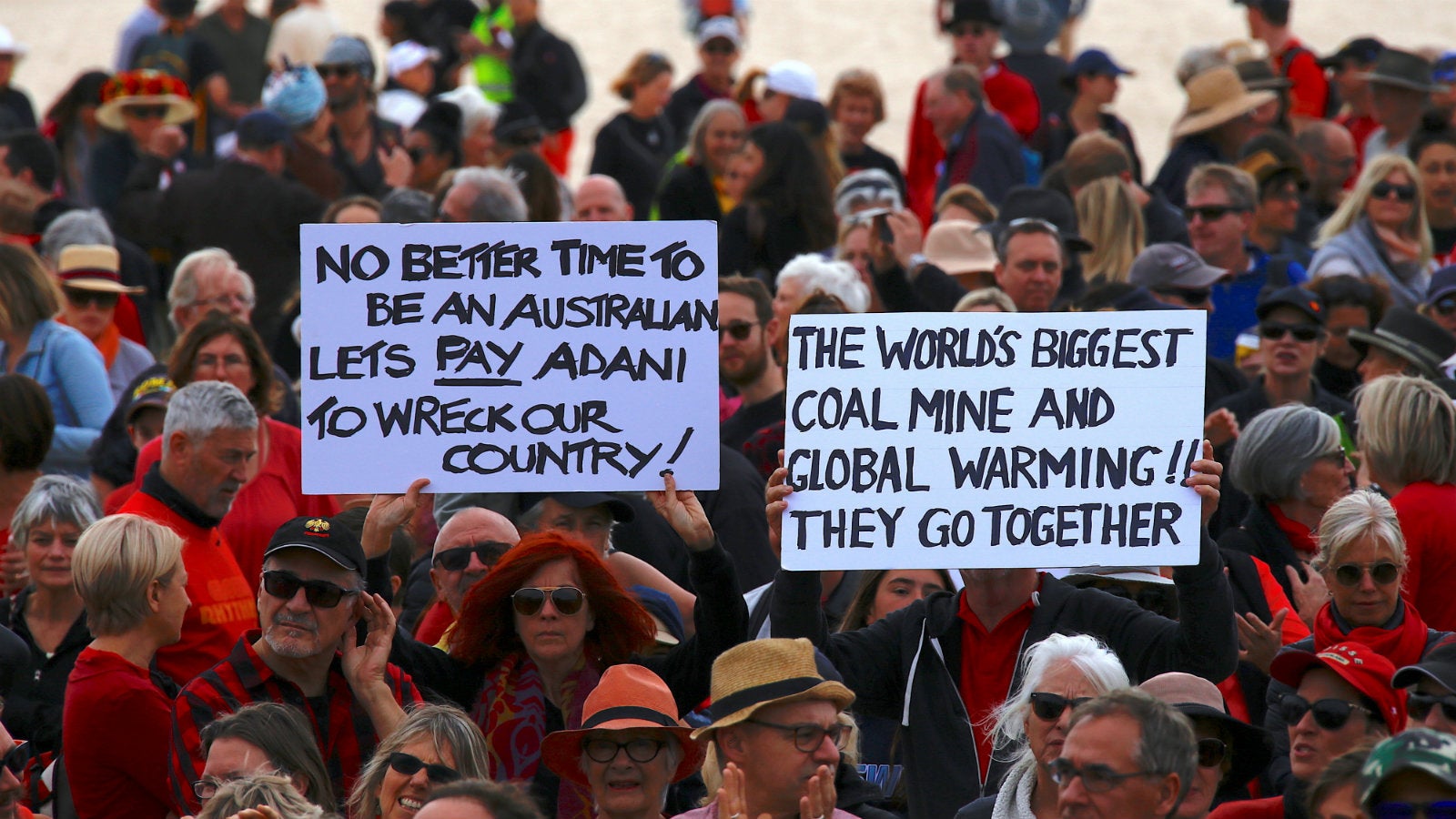

So what could be going on? Perhaps Gautam Adani is willing to lose a large share of his wealth simply to show he can’t be pushed around. Alternatively, as on numerous previous occasions, his promises of an imminent start to work may prove to be baseless.

The third, and most worrying, possibility is that the political pressure to deliver the promised Adani jobs will lead to a large infusion of public money, all of which will be lost.

The A$900 million Adani sought from the Northern Australia Infrastructure Facility in 2017 would be enough to keep the project going for a couple of years, without the need for Mr Adani to risk his own money. It now appears that a similar sum might be sought from the Export Finance and Insurance Corporation.

All this is speculation. Assuming the approvals come through by the Queensland premier’s self-imposed deadline of June 13, we will find out soon enough whether something happens, or whether something else will stay in the way.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons licence. Read the original article. We welcome your comments at [email protected].