Satellite images show how badly India’s reservoirs dried up

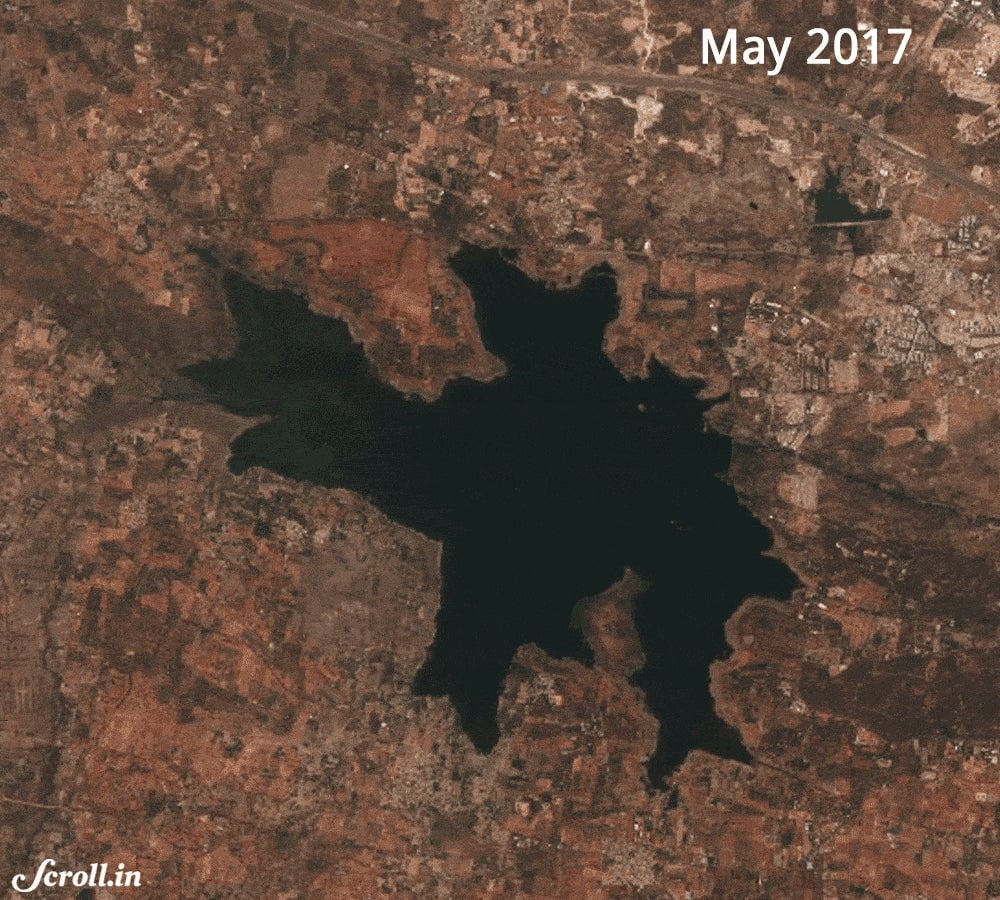

Last week, a time-lapse video showing Chennai’s Puzhal lake shrinking dramatically over the course of seven months earned wide attention. The reservoir is one of the primary sources of water for India’s fourth-largest city, where the water crisis is so severe this year that hospitals have been postponing non-essential surgeries for lack of water in their bathrooms.

Last week, a time-lapse video showing Chennai’s Puzhal lake shrinking dramatically over the course of seven months earned wide attention. The reservoir is one of the primary sources of water for India’s fourth-largest city, where the water crisis is so severe this year that hospitals have been postponing non-essential surgeries for lack of water in their bathrooms.

Reservoirs like Puzhal Lake are rainfed, which means that they rely upon timely precipitation to be recharged. But over the past few years, the monsoons have been growing unreliable.

This year, though the India Meteorological Department predicted that the monsoon would be normal, its onset has been delayed. Pre-monsoon showers have been at theirsecond-lowest level in 65 yearsand the monsoon is currently running a deficit of 35%. As a result, 44% of the country is facing drought conditions.

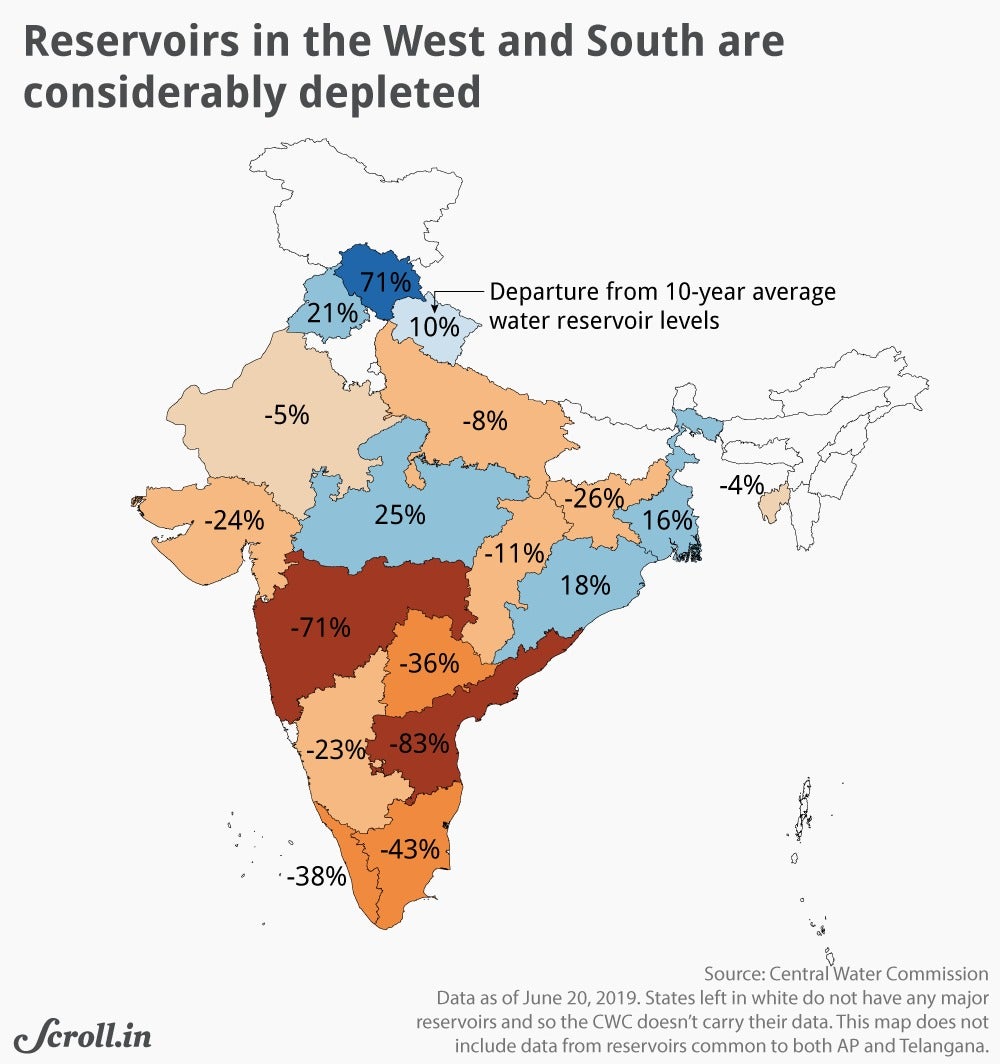

The Central Water Commission, which releases weekly reports on the 91 most important rainfed reservoirs around the country, has dutifully documented this crisis. It has noted that the western and southern states are especially hard hit this year.

The water storage in most of the reservoirs is considerably lower than the 10-year average.

Mumbai

Two of the reservoirs that supply India’s most populous city with water have seen stocks plummet. The Upper Vaitarna reservoir is at 8% of its capacity. At this time last year, it was at 27%. The water level is 70% lower than the 10-year average.

The Bhatsa reservoir is at 24% of its capacity. Its 10-year average for the month of June is 31%, which means it has 21% less water than it normally does at this time of the year.

Five other reservoirs supplying water to Mumbai are also facing a shortfall.

Bengaluru

The Thippagondanahalli reservoir that supplies western Bengaluru with much of its drinking water is running low. The reservoir is located at the confluence of the Arkavathy and Kumudavathi rivers. According to the Bengaluru Water Supply and Sewerage Board, because of the repeated failure of monsoons, the last time the reservoir was full was in 1988.

Hyderabad

The Osman Sagar lake, created by damming the Musi river, is main source of water for Hyderabad. The reservoir nearly dried up in 2016. This year, it has significantly contracted.

Surat

Most cities in south Gujarat, including Surat, get water from the Dharoi reservoir, which stores water from the Sabarmati river. The reservoir is currently at 8% of its capacity—this means 77% less water compared to the 10-year average for June.

The second- and third-most populous cities in India, Delhi and Kolkata, depend upon perennial rivers for their water needs. Delhi gets its water from the Yamuna river, while Kolkata uses water from the Hooghly river, a distributary of the Ganga. Since these rivers are fed by melting glaciers, their flow is not as dependent on the vagaries of the monsoon.

Southern and western India, which depend on rainfed rivers, have been the worst affected regions this summer. Data from the Central Water Commission shows Andhra Pradesh has 83% less water in its reservoirs than the long-term average, while water levels in Maharashtra are 71% lower than the long term average.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].