There’s much more than national prestige driving India’s ambitious moon mission

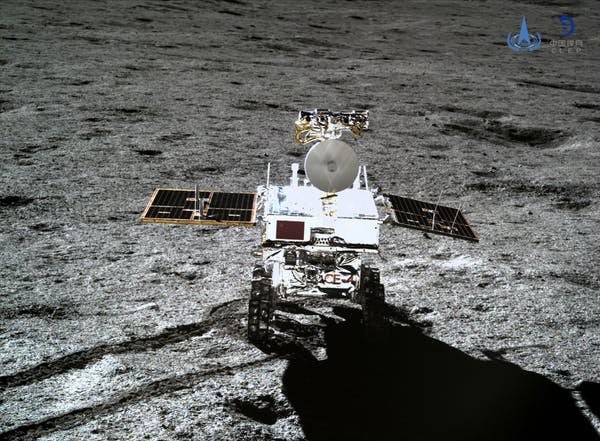

India’s Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft has settled into lunar orbit, ahead of its scheduled Moon landing on Sept. 7. If it succeeds India will join a very select club, now comprising the former Soviet Union, the US and China.

India’s Chandrayaan-2 spacecraft has settled into lunar orbit, ahead of its scheduled Moon landing on Sept. 7. If it succeeds India will join a very select club, now comprising the former Soviet Union, the US and China.

As with all previous Moon missions, national prestige is a big part of India’s Moon shot. But there are some colder calculations behind it as well. Space is poised to become a much bigger business, and both companies and countries are investing in the technological capability to ensure they reap the earthly rewards.

Last year private investment in space-related technology skyrocketed to $3.25 billion, according to the London-based Seraphim Capital—a 29% increase on the previous year.

The list of interested governments is also growing. Along with China and India joining the lunar A-list, in the past decade, eight countries have founded space agencies—Australia, Mexico, New Zealand, Poland, Portugal, South Africa, Turkey, and the United Arab Emirates.

Of prime interest is carving out a piece of the market for making and launching commercial payloads. As much as we already depend on satellites now, this dependence will only grow.

In 2018, up to 382 objects were launched into space. By 2040, it might easily be double that, with companies like Amazon planning “constellations,” composed of thousands of satellites, to provide telecommunication services.

The satellite business is just a start. The next big prize will be technology for “in-situ resource utilisation”—using materials from space for space operations. One example is extracting water from the Moon (which could also be split to provide oxygen and hydrogen-based rocket fuel). NASA’s administrator, Jim Bridenstine, has suggested Australian agencies and companies could play a key role in this.

All up, the potential gains from a slice of the space economy are huge. It is estimated the space economy could grow from about $350 billion now to more than $1 trillion (and as possibly as much $2,700 billion) in 2040.

Launch affordability

At the height of its Apollo program to land on the Moon, NASA got more than 4% of the US federal budget. As NASA gears up to return to the Moon and then go to Mars, its budget share is about 0.5%.

In space, money has most definitely become an object. But it’s a constraint that’s spurring innovation and opening up economic opportunities.

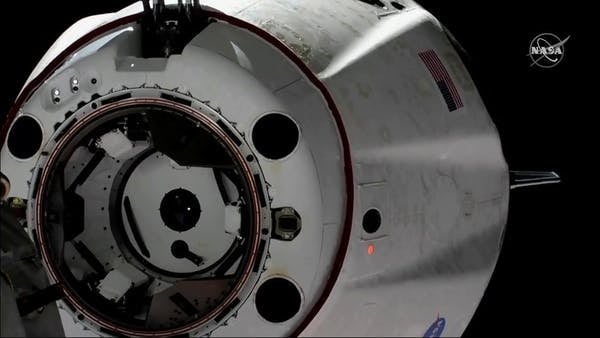

NASA pulled the pin on its space shuttle program in 2011 when the expected efficiencies of a resusable launch vehicle failed to pan out. Since then it has bought seats on Russian Soyuz rockets to get its astronauts into space. It is now paying SpaceX, the company founded by electric car king Elon Musk, to deliver space cargo.

SpaceX’s stellar trajectory, having entered the business a little more than a decade ago, demonstrates the possibilities for new players.

To get something into orbit using the space shuttle cost about $54,500 a kilogram. SpaceX says the cost of its Falcon 9 rocket and reuseable Dragon spacecraft is about $2,700 a kilogram. With costs falling, the space economy is poised to boom.

Choosing a niche

As the space economy grows, it’s likely different countries will come to occupy different niches. The specialisation will be the key to success, as happens for all industries.

In the hydrocarbon industry, for instance, some countries extract while others process. In the computer industry, some countries design while others manufacture. There will be similar niches in space. Governments’ policies will play a big part in determining which nation fills which niche.

There are three ways to think about niches.

First, function. A country could focus on space mining, for instance, or space observation. It could act as a space communication hub, or specialise in developing space-based weapons.

Luxembourg is an example of functional specialisation. Despite its small size, it punches above its weight in the satellite industry. Another example is Russia, which for now has a monopoly on transporting astronauts to the International Space Station.

Second, value-adding. A national economy can focus on lower or higher value-add processes. In telecommunications, for example, much of the design work is done in the US, while much of the manufacturing happens in China. Both roles have benefits and drawbacks.

Third, blocs. Global production networks sometimes fragment. One can already see the potential for this happening between the US and China. If it occurs, other countries must either align with one bloc or remain neutral.

Aligning with a large power ensures patronage, but also dependence. Being between blocs has its risks, but also provides opportunities to gain from each bloc and act as an intermediary.

The first space race, between the Soviet Union and the US, was singularly driven by political will and government policy. The new space race is more complex, with private players taking the lead in many ways, but government priorities and policy are still crucial. They will determine which countries reach the heights, and which get left behind.

This piece was first published on The Conversation. We welcome your comments at [email protected].