Climate change caused warming could kill 1.5 million Indians each year by 2100

On a day when India’s capital city continued to be engulfed in toxic post-Diwali smog, a new study provided a peek into the country’s bleak future if greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow at high rates: a spike in temperatures, and with it, a rise in mortality.

On a day when India’s capital city continued to be engulfed in toxic post-Diwali smog, a new study provided a peek into the country’s bleak future if greenhouse gas emissions continue to grow at high rates: a spike in temperatures, and with it, a rise in mortality.

Released at an event in Delhi yesterday (Oct. 31), the report by the Climate Impact Lab in collaboration with the Tata Centre for Development at UChicago estimates that by 2100, around 1.5 million more people could die in India each year due to climate change.

Six states, Uttar Pradesh (402,280), Bihar (136,372), Rajasthan (121,809), Andhra Pradesh (116,920), Madhya Pradesh (108,370), and Maharashtra (106,749) are estimated to contribute 64% of the total excess deaths.

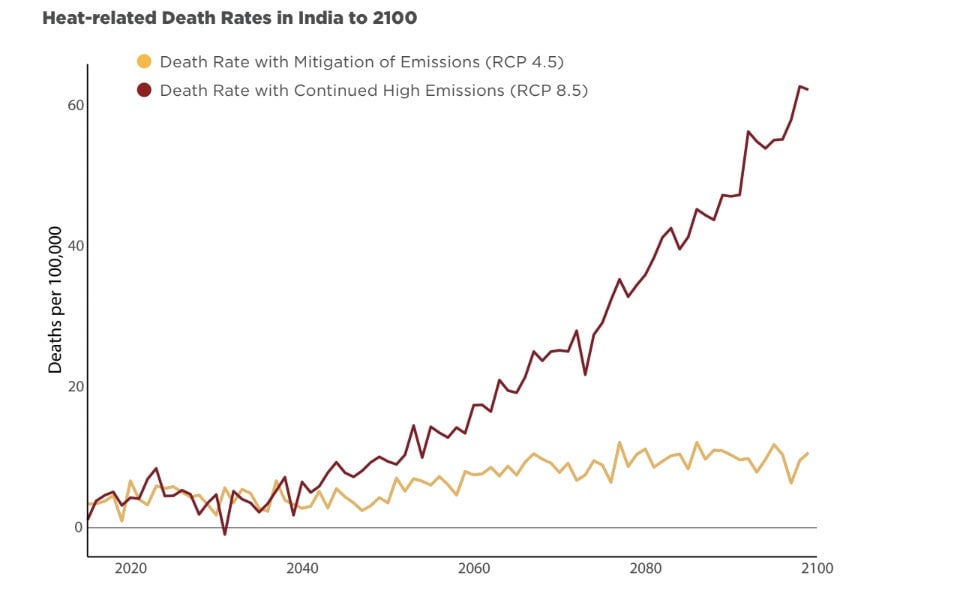

The study looks at two different scenarios for estimating temperature rise and its impact on mortality. The first—RCP 4.5—is based on the assumption that carbon-dioxide levels in the atmosphere will peak around 2040 and reach 540 parts per million (ppm) by 2100. The second—RCP 8.5—assumes that emissions will continue to rise through the 21st century and carbon-dioxide levels will reach 940 ppm by the end of the century.

The world is currently on track to breach the RCP 4.5 scenario but not quite on the RCP 8.5 trajectory. Despite that, it’s important to analyze worst-case scenario to understand risks and work on mitigating harms. In the high-emission scenario, for instance, Delhi will likely see 23,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2100.

At the end of the century, 16 of the 36 states and union territories in India will have average temperatures hotter than Punjab, which currently has the highest average summer temperature.

Extremely hot days are expected to greatly increase in India. Delhi is expected to face about 22 times more extremely hot days. Nationally, an eight-fold increase in really hot days of above 35°C is estimated.

In a first, the report looks at climate change as a direct cause of death. Instead of an abstract scenario, it provides costs of climate change using comprehensive data analysis.

“There is no escaping that India is kind of at the perfect-storm centre of the climate challenge,” said Michael Greenstone, the co-founder of Climate Impact Lab, adding: “It’s perfectly positioned to face some of the most severe climate damages in the world.”

The report, he said during a panel discussion following the launch, “underscores the urgency of reducing the rate of climate change.”

It is based on global data on temperature and mortality, covering 57% of the global population. Mortality-temperature relationship estimates were used to generate projections of the future impacts of climate change on mortality rates.

“It’s important to get data from different parts of the world because we can learn about what’s going to happen in India by learning what happens in wealthier countries,” said Amir Jina, a member of the Climate Impact Lab.

“This is why thinking about extremes is important. As we move towards hotter days, mortality will increase sharply. So it’s important for us to think about those extreme changes,” Jina added.

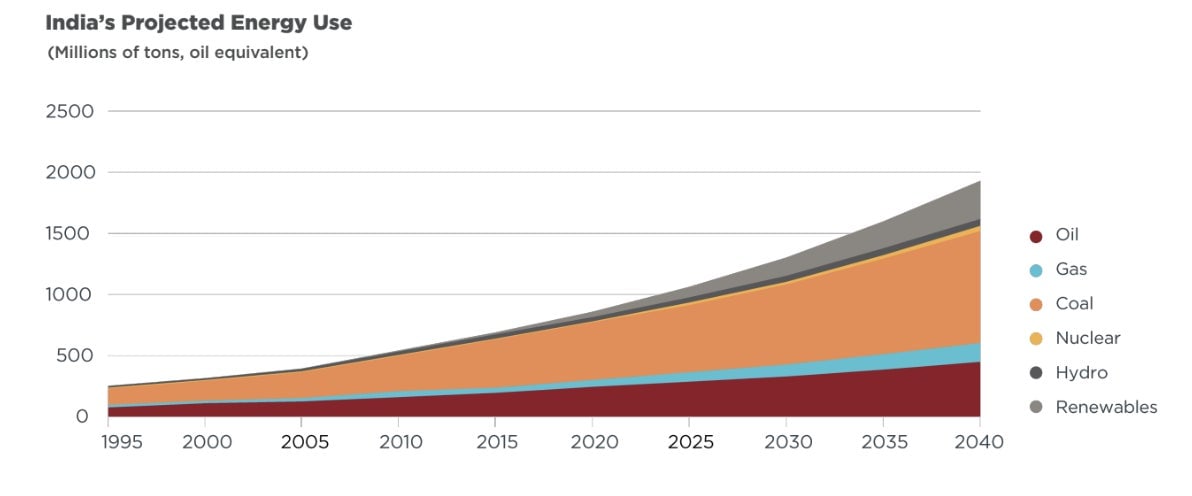

India’s projected energy use is expected to more than double by 2040, with a lot of the growth coming from coal. According to Greenstone, the country must move away from coal and towards natural gas available at low prices around the world. “It would provide benefits today in reducing air pollution and would also have long-term impacts,” he said.

While the study provides a near-apocalyptic scenario of rising temperatures and mortality, according to Kamal Kishore, a member of the National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA), all is not lost. “There is a lot that happens between a heat-wave incident and mortality, which has to do with culture, occupation, people’s inherent vulnerability or resilience,” he said.

Kishore is of the opinion that societies adapt to changes all the time. “Hot days are going to increase, but the society will not be sitting passively. There’s an interaction of two complex systems: climate and social,” he said.

Admitting that “much more needs to happen,” Kishore told Quartz there is now much greater awareness and “much stronger connection between science and the society.”

There is also an increased effort to work across sectors, he said. A heat-wave, for example, is being looked at “not just as a disaster problem or a public health problem, but also something that should be of concern to the departments of labour, drinking water, agriculture and power.” There is, thus, more of a cross-sectorial response.