How Nepal’s democracy, and ties with India, were threatened by an ambitious monarch

On the evening of Jan. 31, 2005, Minendra Rijal, a Congress leader close to (Nepal’s) prime minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, was at a cocktail party. The deputy chief of mission at the Indian embassy, VP Haran, approached him and asked, “Is the king up to something?” Rijal had no knowledge of anything, so he quickly contacted home minister Purna Bahadur Khadka.

On the evening of Jan. 31, 2005, Minendra Rijal, a Congress leader close to (Nepal’s) prime minister Sher Bahadur Deuba, was at a cocktail party. The deputy chief of mission at the Indian embassy, VP Haran, approached him and asked, “Is the king up to something?” Rijal had no knowledge of anything, so he quickly contacted home minister Purna Bahadur Khadka.

The minister contacted the police chief, Shyam Bhakta Thapa. IGP Thapa took the call as he was returning from the palace with the chief of the armed police force, Sahabir Thapa, and chief of the Nepal’s national investigation department Devi Ram Sharma. They had just been briefed about the royal step planned for the next day. But since they were told to keep it top secret, IGP Thapa was unable to reveal details, even to the home minister. He just hinted that “something was cooking.” Minister Khadka then told Rijal that “security was on red alert.” Perhaps the minister himself did not know anything more than that.

Early in the morning of Feb. 1, a well-known Indian national working at the Everest Hotel was told by a person who delivered flowers to the palace that “something is about to happen.” The Indian shared the information with the Indian embassy. Quickly, the information was relayed to Delhi.

According to Devi Ram Sharma, the RAW (research and analysis wing) chief called him and said in a warning tone, “We are following the policy of supporting the twin pillars of constitutional monarchy and multiparty democracy. But if the king breaches it, we will no longer be compelled (to continue doing so).” Sharma informed the palace about the conversation, but King Gyanendra had already made up his mind. At 10am, he addressed his subjects through radio and television and declared the royal takeover by invoking Article 127 of the 1990 constitution.

Actually, the king had wanted to take this step after taking the Indian political leadership into confidence. He had therefore been trying to visit Delhi for a long time—but Delhi kept postponing his visit. He was finally scheduled to go to Delhi on a 10-day visit beginning Dec. 23, 2004. The royal couple was about to get in the car for the airport. The prime minister had already reached the airport to see them off. Right at that moment, Indian prime minister Manmohan Singh himself called King Gyanendra, to inform him about the demise of former Indian prime minister PV Narasimha Rao. He regretted that the visit had to be postponed.

Three days later, India faced a natural calamity in its coastal areas caused by the tsunami. The king’s visit was as good as cancelled. The king had wanted to make his move only after visiting Delhi, so that he could garner support there. When it became impossible, he went ahead anyway on Feb. 1, 2005, planning to gain Indian support later.

Strong reaction

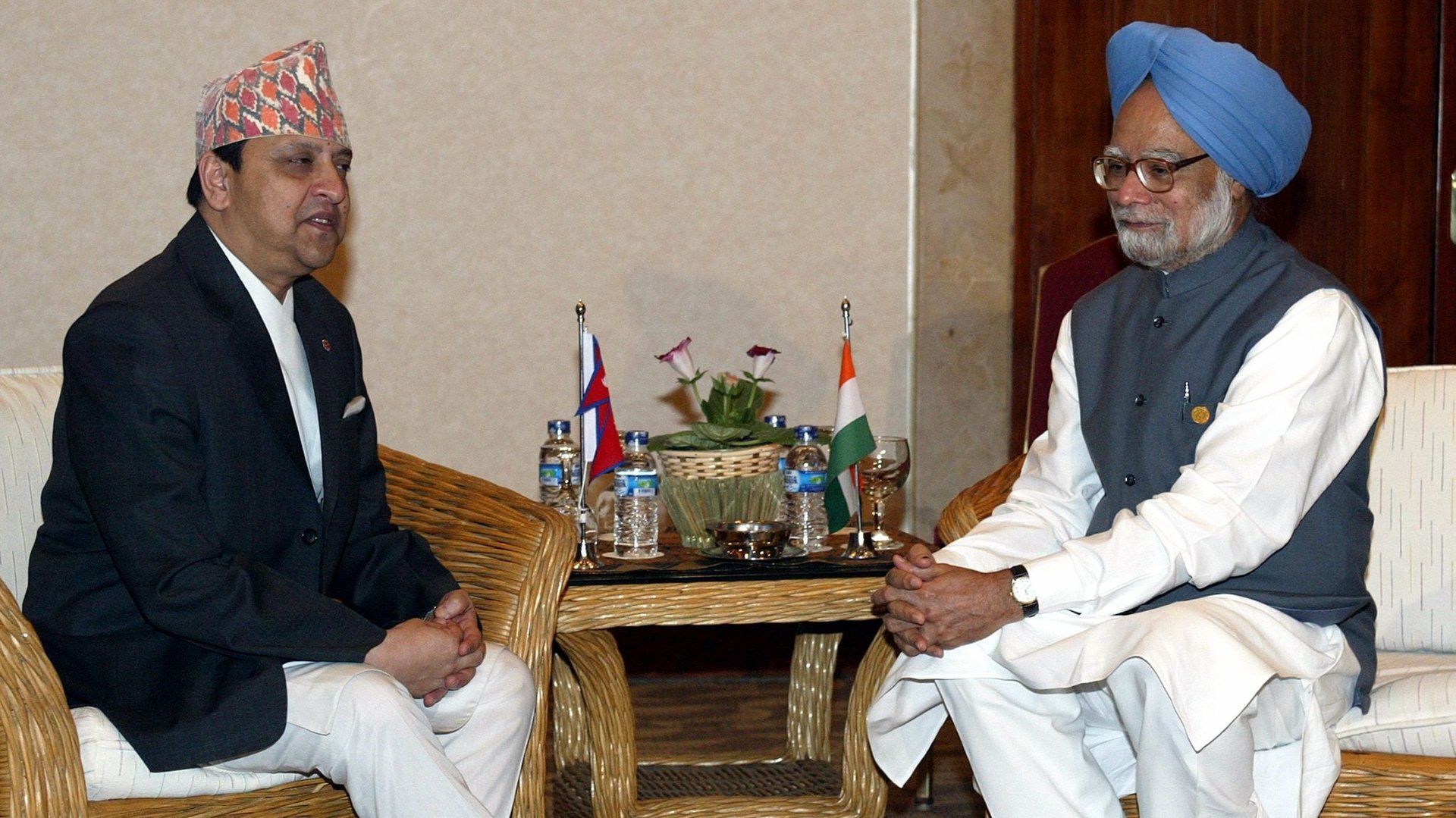

Immediately after the royal coup in Kathmandu, Indian prime minister Singh called an emergency meeting of his cabinet security committee to review the latest Nepal situation. After the meeting, India took a strong position against King Gyanendra, which was evident in the statement issued by the external affairs ministry. Shyam Saran, who had maintained a hawkish attitude against the palace during his stint as ambassador in Kathmandu, was now the head of South Block.

Saran issued a strong statement deploring the royal step: “India has consistently supported multiparty democracy and constitutional monarchy enshrined in Nepal’s constitution as the two pillars of political stability in Nepal. This principle has now been violated with the king forming a government under his chairmanship. The latest developments in Nepal bring the monarchy and the mainstream political parties in direct confrontation with each other.” The statement added that such a step would only benefit the Maoists as a force that stood against both the democracy and the monarchy.

India had not objected earlier when King Gyanendra had appropriated some executive power. But on Feb. 1, India concluded that the king had gone too far. Neither democracy nor constitutional monarchy was being maintained. Besides, the king had kept Delhi in the dark.

Five days after he took power, the 13th SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) Summit began in Dhaka, on Feb. 6. The king’s plan was to attend the summit himself, brief the regional leaders about the “compulsion” that forced him to take the step, and win their support. He was preparing to extend a hand of friendship to prime minister Singh at the summit. But when the Indian prime minister declared his inability to attend, on security grounds, Bangladesh was compelled to suspend the summit. Earlier, on the third day after the royal step, the Indian army chief, JJ Singh, had cancelled his scheduled visit to Nepal.

These were all attempts to pressure King Gyanendra. But he did not appear to be under pressure. Rather, he kept on trying to contact the Indians for support. He instructed his foreign minister Ramesh Nath Pandey to talk to Indian ambassador Shiv Shankar Mukherjee two days after the coup. On Feb. 8, he sent the army chief, Pyar Jung Thapa, to meet Mukherjee. The following day, he himself spoke to Mukherjee. None of the three meetings were fruitful. Talking to journalists in Bengaluru, Indian prime minister Singh said, “What has happened (in Nepal) is a setback for democracy. India hopes that there will be a change for the better and democracy will be restored at the earliest.”

The palace had expected political opposition to its step from India, but what really startled it was when Delhi stopped the supply of military material. India made a formal announcement on Feb. 22 that it was stopping military assistance and supplies to Nepal, to apply pressure on the king. After its foreign secretary Jack Straw visited India and consulted with Delhi on Nepal, in the third week of February, the UK also announced the suspension of military assistance. And on March 16, US secretary of state Condoleezza Rice, during a visit to Delhi and after talks with Indian external affairs minister Natwar Singh, stated that India and the US were in full agreement that Nepal should return to the path of democracy at the soonest.

The Royal Nepali Army was piqued at the decision of India and other countries to stop military aid. The army spokesperson said, “It is an unfortunate decision. It will ultimately assist terrorism and the so-called people’s regime of the Maoists.” The palace was under pressure to ensure the resumption of military aid in order to prevent soldiers from becoming demoralised. Foreign minister Pandey had a “working lunch” with his Indian counterpart Natwar Singh in Delhi on March 7. He tried to convince Singh about the necessity of the royal step. He was actually carrying with him a list of military wares they needed.

Jakarta encounter

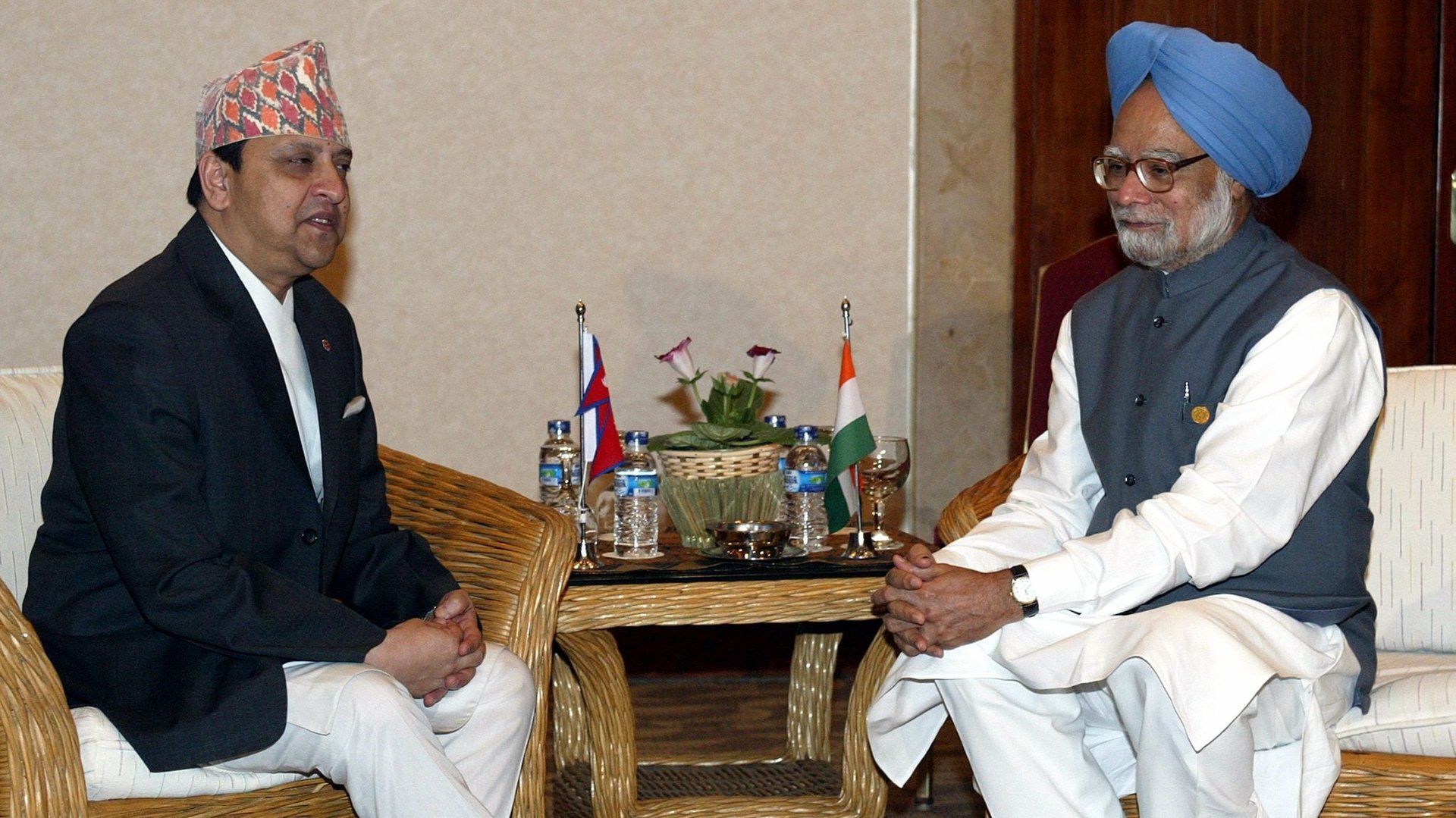

The Indonesian capital Jakarta was hosting a conference of Afro-Asian nations a few days later. King Gyanendra wanted to meet Singh in Jakarta. So, on the eve of his departure to Jakarta, he released a few political detainees, including former prime ministers Girija Prasad Koirala and Sher Bahadur Deuba, and declared municipal elections. Still, Singh was not willing to meet him. It was only after he sought help from Singh’s national security advisor MK Narayanan that the meeting could be confirmed.

When he spoke to Singh for forty-five minutes on April 23, King Gyanendra basically made two points. One, if the Indians did not resume military supplies, the Maoists could take over. Two, Nepal would be compelled to seek help from China and Pakistan if India remained adamant. Meanwhile, the king had held a telephone conversation with the Pakistani prime minister, Shaukat Aziz, to seek assistance. Pakistan extended full support to the royal regime.

India was in a fix. It neither wanted to see a Maoist takeover, nor wanted China or Pakistan to step into its zone of influence. Therefore, it exhibited flexibility by setting some conditions. NSA MK Narayanan was trying hard to repair Delhi-Durbar relations, while external affairs minister Natwar Singh also lent a hand in this direction. Natwar Singh, in fact, hailed from the same Jat princely family of Rajasthan whose daughter had married Gyanendra’s only son, Paras.

The Indian Army, which considers the Nepali Army its “brother army,” was also pressuring the Indian government for a resumption of supplies. Their logic was that the army was the strongest institution in Nepal, and India should not reduce its influence over the army. The Indian army leadership reiterated that if they did not help, China or Pakistan would come forward. It was also said that continued pressure on Nepal would negatively affect the morale of over 50,000 Gorkha soldiers in the Indian army.

Due to these reasons, India was ready to resume military supplies. The condition was that the king should be clearly seen to be restarting the political process. The king had also committed, in Jakarta, to release all political leaders, talk to them, call an election, and form an elected government. Yet, on April 28, former Nepal prime minister Deuba was rearrested on charges of corruption in the Melamchi water project.

However, possibly having understood Delhi’s predicament, the king lifted the state of emergency on April 30 and released a few more detainees. On May 8, on her way to Nepal, the US assistant secretary of state Christina Rocca visited New Delhi, and was able to convince the Indians to give the king the benefit of doubt. The next day, Indian ambassador Mukherjee informed the king of Delhi’s decision to resume military supplies.

Excerpted from Sudheer Sharma’s The Nepal Nexus with permission from Penguin Randomhouse India. We welcome your comments at [email protected].