As inflation firms up, India’s central bank may not be able to play rate-cut Santa for long

India’s central bank, already having cut interest rates five times on the trot this year, may quickly be running out of room to ease up even more. Here’s why.

India’s central bank, already having cut interest rates five times on the trot this year, may quickly be running out of room to ease up even more. Here’s why.

Retail inflation in October, measured by the consumer price index (CPI), stood at a 16-month high of 4.62%, showed data released yesterday (Nov. 13) by India’s ministry of statistics and programme implementation. This breaches the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) comfort zone of under 4%.

Higher inflation in the month was triggered by a spike in the prices of vegetables (26.1%) and pulses (11.72%), the supplies of which were disrupted due to rains.

Retail onion prices, for instance, hovered around Rs80 ($1.11) per kilogram in Delhi in early November, as against Rs55 a month ago. Prime minister Narendra Modi’s government is now resorting to imports.

Higher food prices could impact retail inflation in the short term at least, according to CARE Ratings. “This number (CPI inflation) will remain elevated for the next couple of months before being moderated. By March-end it should be around 4%, though it can go higher in November due to an unfavourable base,” an agency note said following the release of the inflation data.

Another cut?

RBI will have to tackle the high inflation-low growth conundrum at its next monetary policy committee (MPC) meeting on Dec. 3-5, and experts are divided on what its stance could be.

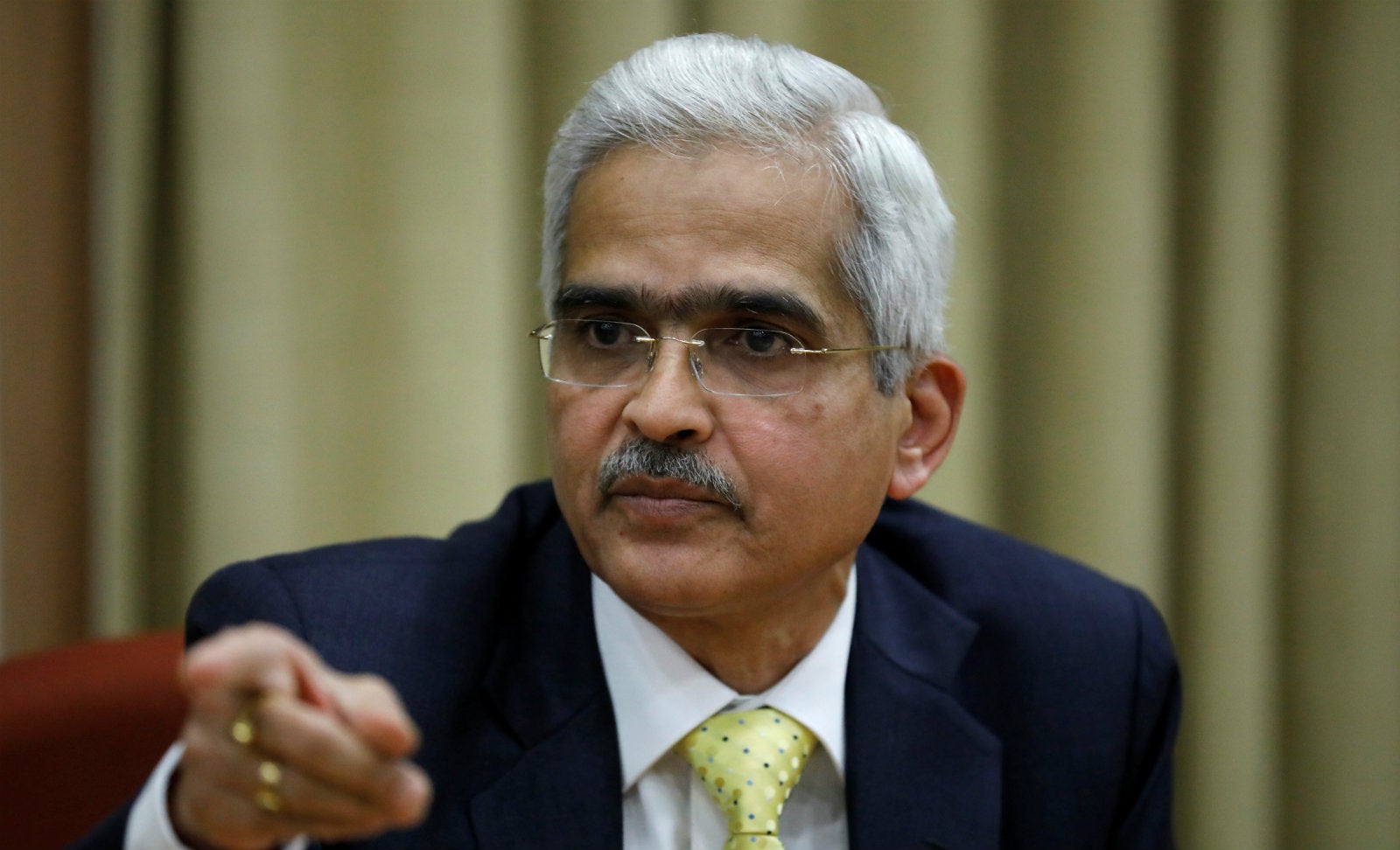

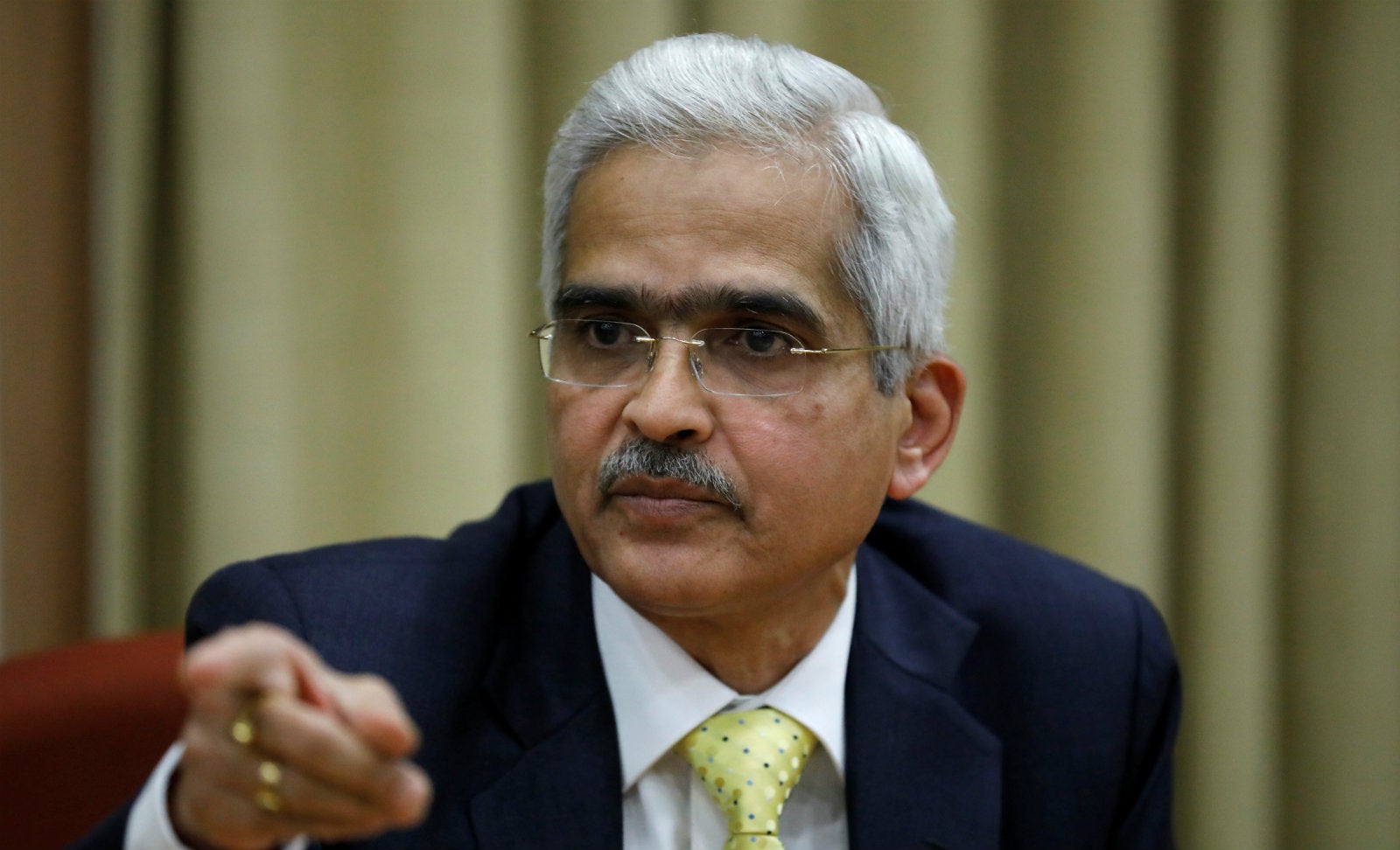

Some expect RBI governor Shaktikanta Das to overlook the latest data as the economy has shown no signs of revival.

The ministry’s data, for instance, showed that core inflation, which excludes food items, falling from 4% in September to 3.5% in October. This reflects weak demand. Industrial output, too, contracted 4.3% in September, the worst performance in eight years, according to data released on Nov. 11.

The result may be a further deceleration in GDP growth in the July-September quarter, from the five-year low of 5% in the preceding one.

“Growth concerns have become far more important than inflation in the current context. We expect growth in the second quarter (July-September) to come in at 4.5% which would be a big concern,” Anagha Deodhar, an economist at ICICI Securities, told Reuters. Deodhar added that the RBI is not done with the rate cut cycle yet.

So far this year, the central bank has cut the repo rate, at which it lends to commercial banks, by a cumulative 135 basis points (one basis points is one-hundredth of a percentage point).

Economists at CARE, though, have a different take: “We do not expect RBI to go in for a rate cut in the next monetary policy even though growth concerns are sharp.” At 4-4.5%, inflation will hover above the RBI’s target for the remainder of the financial year, CARE noted.

What is certain, though, is that, unlike the earlier monetary policy decisions this year, RBI’s choice is not so clear cut this time.