How brands are hurting themselves with pan-India “Hinglish” ads

It started in the late ’90s when PepsiCo localised its global “Ask for more” ad campaign, with “Yeh dil maange more!” (This heart wants more!)

It started in the late ’90s when PepsiCo localised its global “Ask for more” ad campaign, with “Yeh dil maange more!” (This heart wants more!)

The hit tagline legitimised the Hindi-English language jumble in Indian advertising. Not to be outsmarted, Coca-Cola soon replied with “Life ho to aisi.” (That’s how life should be).

Mixing Hindi and English came easily to the informal world of Indian advertising. Pepsi continued to use Hindi loan words in ad campaigns like “Yehi hai right choice, baby,” (This is the right choice, baby), for instance.

Of late, though, the unbridled use of Hindi in English newspaper ads has exceeded reasonable limits. It’s unfair, and also does not work as a campaign strategy even when written in Roman script, for the millions of regional language speakers who know only a smattering of Hindi.

Here’s a sample of the malaise.

Hinglish, Hinglish everywhere

This multi-edition advertisement by two-wheeler maker Honda appeared in The Times of India newspaper on Oct. 6, 2018. Across the paper’s four editions in south India, the headline, written in Roman script, conveys the message in Hindi, which is not the language of choice in the region.

This is not an isolated incident. Here’s an ad by OLX, an online marketplace for used goods.

And this one by Sugarlite, a sugar substitute manufactured by Zydus Wellness.

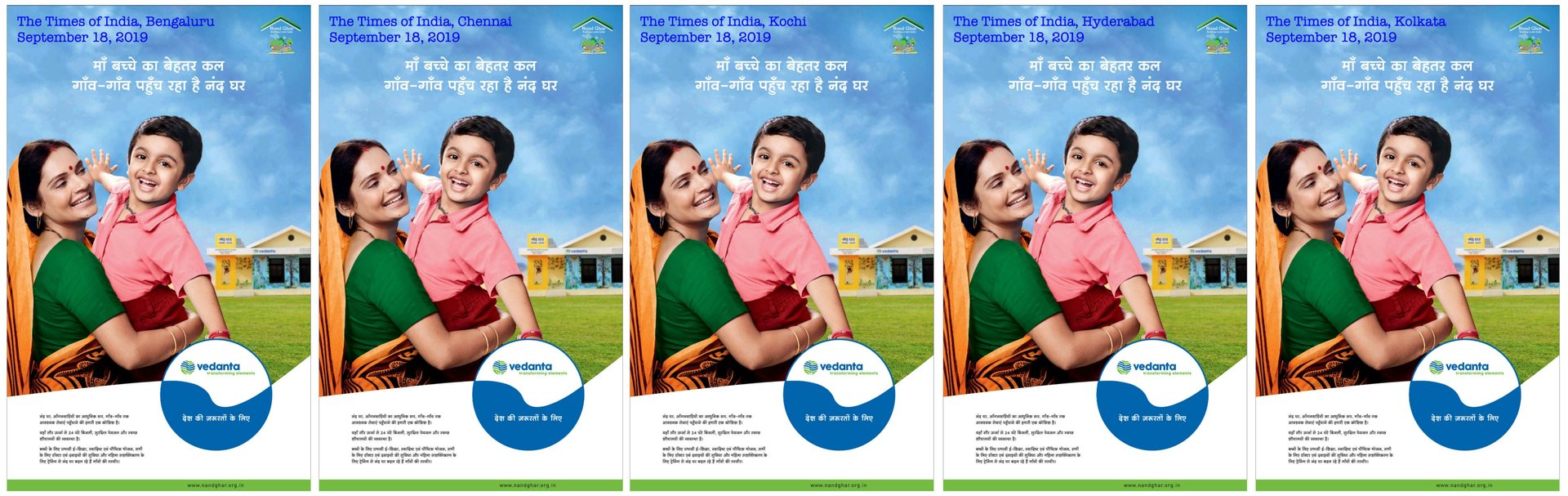

Vedanta, though, takes the cake for its use of the Hindi script across all editions in India.

Regional language newspapers offer translated versions of the same headline, but, more often than not, it is poorly transliterated and mauls the intended message.

A question then arises: why do brands carry Hindi headlines at all, even in regions where Hindi is not commonly used? What stops brands from persuading consumers in Chennai, say, with Tamil ads written in Roman script?

Even after ignoring the false argument that Hindi is India’s national language, some claims still stand out.

“Hindi is widely spoken”

One persistent argument is that these brands are targeting “the sizeable” Hindi-knowing audience in cities like Chennai and Bengaluru.

They also claim Hindi headlines are understood by a large section of people there, even if their knowledge of Hindi is superficial (through movies and music). “If they understand the headline, what is the problem? The message gets through, no?”

Here’s the chink in the argument, though: Advertising is not mere communication. It’s persuasion. Your audience must crave what you are selling.

As the British advertising tycoon David Ogilvy wrote: “If you’re trying to persuade people to do something, or buy something… you should use… the language they use every day, the language in which they think.”

If you want to persuade the audience in a region using the largest-circulated English newspaper there, why not take that extra effort to talk like them?

To reiterate, the crux of this strategy is marketing effectiveness and not language chauvinism. Brands cannot impose anything, let alone Hindi. They are in the business of persuading consumers.

Cost factor

Another argument is around cost—brands can’t pay for multiple creatives. Hence a common creative across all major editions, with a Hindi headline in Roman script, is cheaper.

If brands buy ad space in one key edition, like Delhi or Mumbai, many other editions are thrown in for a cheap add-on price by the newspaper, provided the creative is the same.

This may sound like a competent argument, till you realise that brands spend crores to buy space in the media, in any case. The incremental, operational expense of having more creatives pales in comparison to those crores, given the advantage of using the local tongue.

A more reasonable argument revolves around translation.

Almost all national advertising agencies in India are headquartered in Mumbai and Delhi. They outsource translations to agencies that handle transactions on a large scale. The time to get a contextual translation (not transliteration) done would increase the time to take the communication to the market. Considering how overnighters are the norm in most agencies, such liberties are hardly available.

The result: Hindi chalega! (Hindi works!)

This is amplified by the fact that most creative heads at India’s national agencies are conditioned to think Hindi first.

Even if creative directors are non-Hindi speaking people, the chances are, the client leader is Hindi-speaking and wants precisely that—a central thought in English and Hindi. The rest can be translated, if they are in a generous mood, or… Hindi chalega!

A campaign backfires

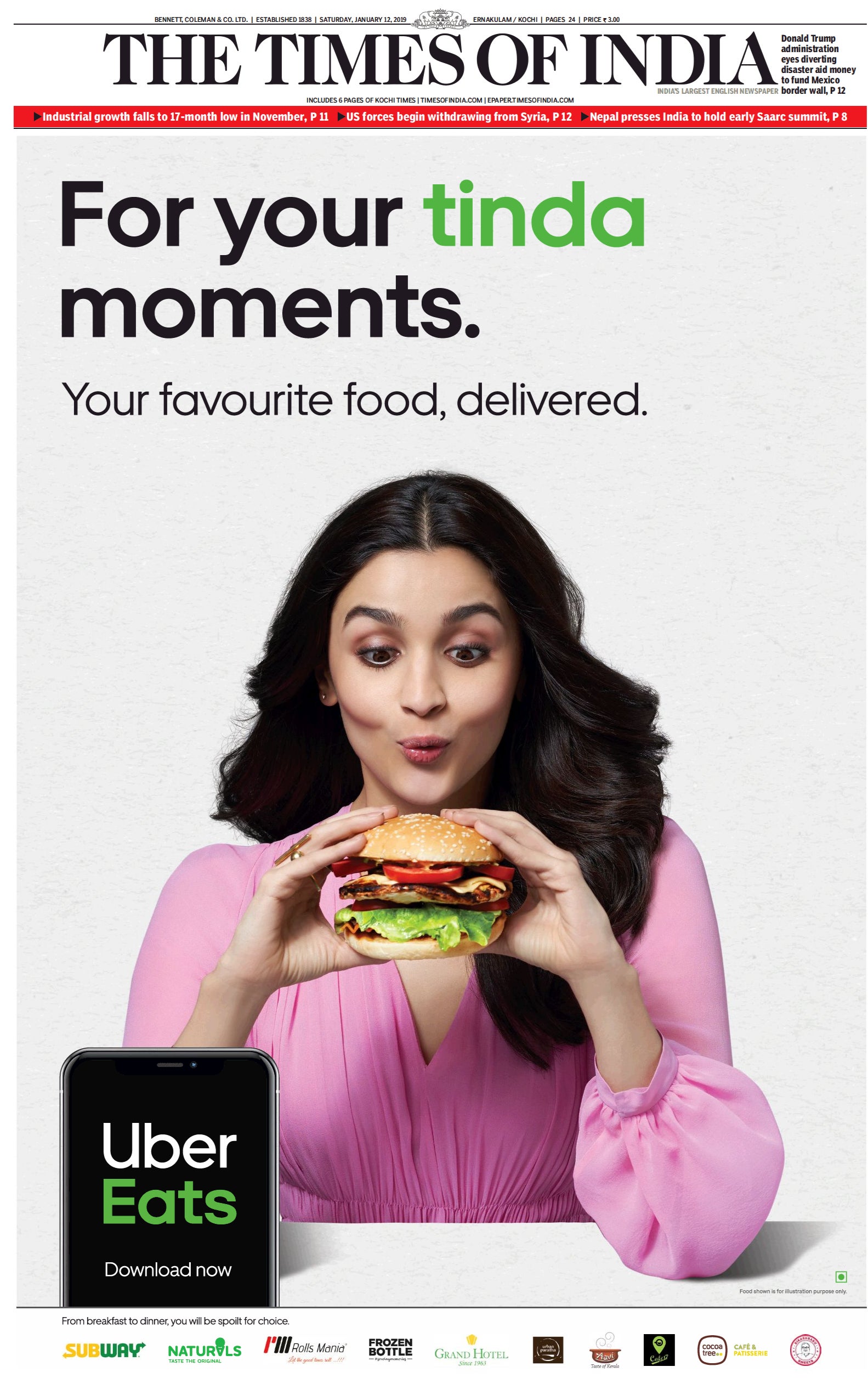

The Hindi predominance manifested in an amusing situation recently in an Uber campaign.

On Jan. 12, Uber Eats released a full-page, multi-edition ad campaign that proudly announced that Uber Eats is for the “Tinda moments!” Bollywood diva Alia Bhatt was seen talking about “Tinda moments” in a TV ad, one where she orders on Uber Eats because there’s “tinde ki sabzi” at home.

In Hindi-speaking regions, the connection with the banal vegetable is easy to make, but not in other places.

Some thought Uber Eats was, for some reason, indulging in a wordplay around the dating app Tinder. But most reacted with a blank expression.

Eventually, Uber Eats understood the blunder and went out of its way to think beyond Hindi. They looked at bland or hated food items in each region. They even signed local brand ambassadors to join Alia!

Having observed, researched and spoken about this growing Hindi trend for well over a year, I have come to believe that the obsession with Hindi as a pan-Indian communication medium (along with English) is simply out of ignorance and lack of intent.

Think out of the Delhi-Mumbai box

Interestingly, when an ad campaign emanates from outside Mumbai or Delhi, the creators are confident of using the local language written in Roman script!

Chennai-based brands and agencies have a history of using Tamil in Roman script as an eye-catching, colloquial device to break the English flow in an English newspaper!

Thankfully, some national brands, too, are trying to turn a new leaf.

Here’s ET Money, using their headline in six different Indian languages, all written in the Roman script.

Appreciate the local

The first step to bring a change in this situation is to appreciate local cultures. For this, they don’t need to look far.

Prime minister Narendra Modi or home minister Amit Shah, when they start a speech in Guntur or Tuticorin, start with a few badly-pronounced sentences in Telugu or Tamil.

Our PM, always the master of marketing and presentation, wore a veshti all through the Mahabalipuram summit with the Chinese Premier, to offer a local hook for people to hold on to.

Having a local language headline in Roman script has the same effect in print advertising.

Mondelez, the makers of Cadbury, turned the whole localisation drive on its head during their Independence Day campaign this year. While their ads in the south were written in the Devanagari script, used in Hindi and its sister languages, the ads in Delhi and Mumbai were in south Indian languages.

It gave a taste of what people in Kochi or Coimbatore go through when they see a Hindi headline!

We welcome your comments at [email protected].