India’s new Citizenship Act and national register of citizens are both inspired by “paranoia”

India’s contentious Citizenship Amendment Act, which was cleared by parliament last week, has sparked violent protests across the country, for more than one reason. While there is anger that the legislation is discriminatory against Muslims, there are also fears of an influx of settlers.

India’s contentious Citizenship Amendment Act, which was cleared by parliament last week, has sparked violent protests across the country, for more than one reason. While there is anger that the legislation is discriminatory against Muslims, there are also fears of an influx of settlers.

The legislation aims to fast-track citizenship for persecuted Hindus, Parsis, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, and Christians who arrived in India before Dec. 31, 2014, from Bangladesh, Pakistan, or Afghanistan. For the immigrant religious minorities, the law effectively amends India’s Citizenship Act, 1955, which required an applicant to have resided in India for 11 years.

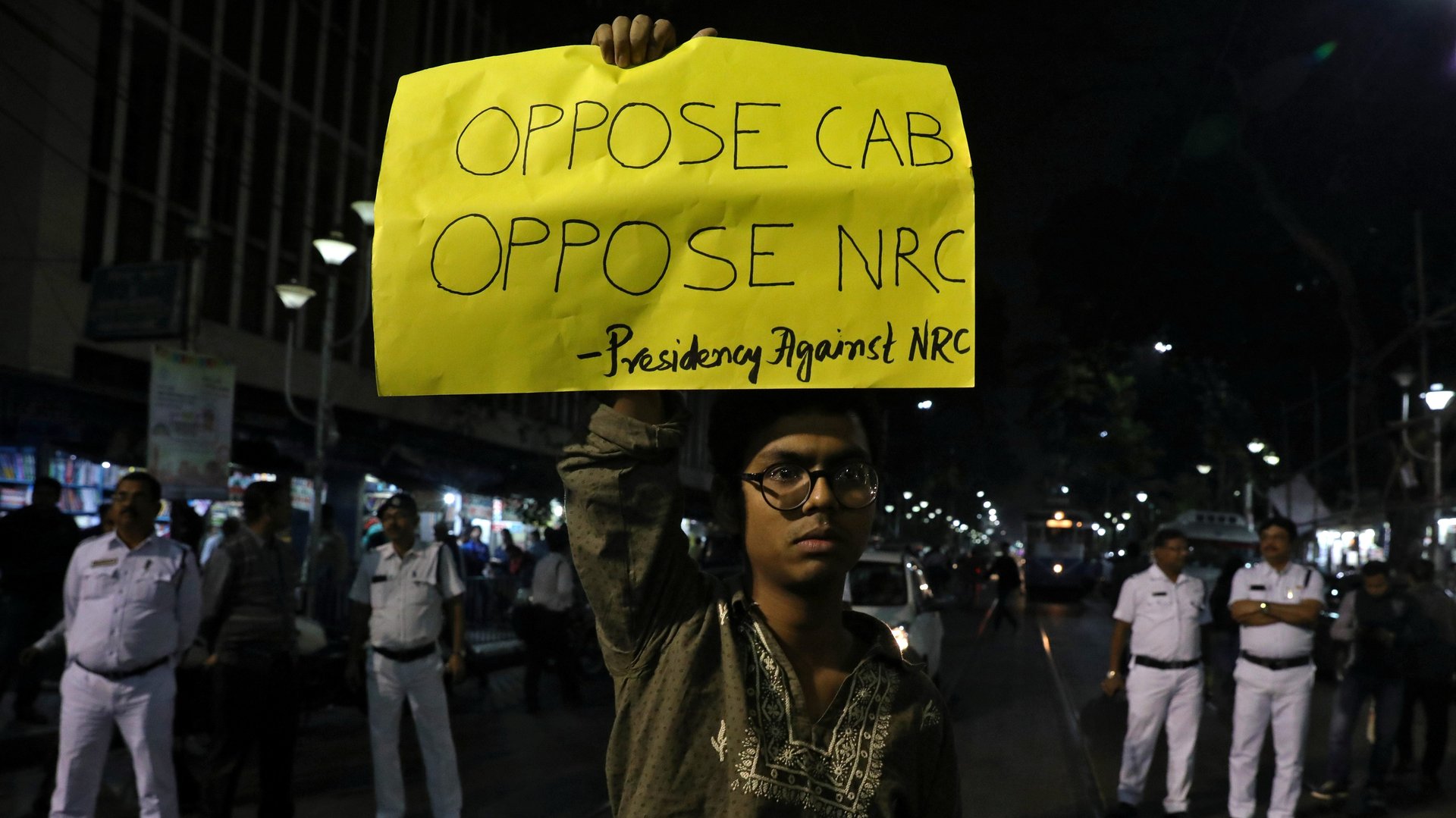

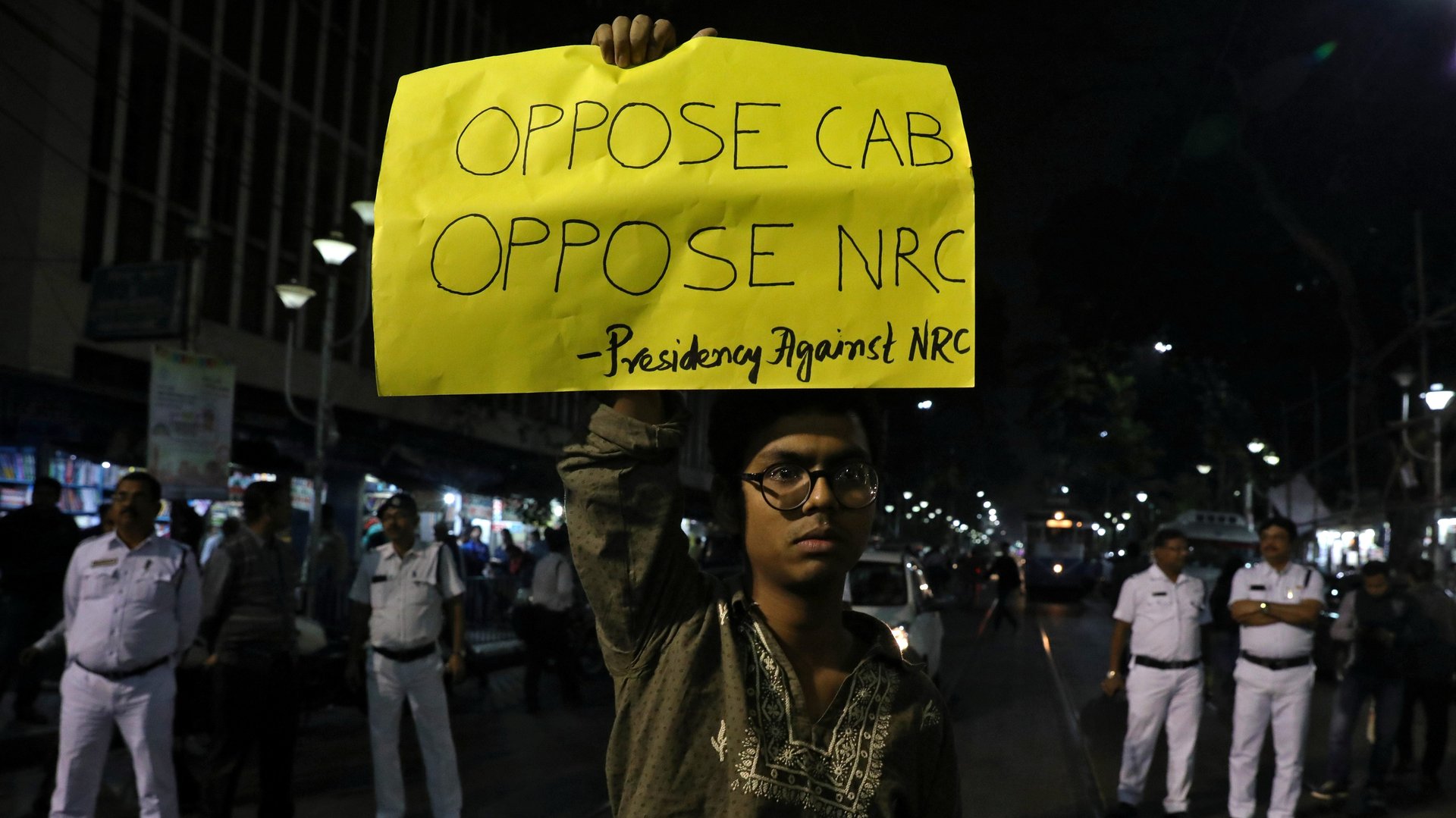

The upheaval in most of the country, is due to the exclusion of Muslims from the list. Rohingya Muslims fleeing from Myanmar, for instance, will not be given citizenship under the new law. Likewise, for Sri Lankan Tamils. Several people took to the streets in West Bengal, Kerala, and Goa, and some protests turned violent. In Delhi, police allegedly resorted to tear-gas shells, guns, and batons to push back protestors at Jamia Millia Islamia university.

In the northeast, though, the resistance to the legislation has a different hue.

The NRC piece

In Assam, which shares a border with Bangladesh, people fear an ethnic, and demographic shift due to an influx of immigrants—regardless of their religion. Violent protests in state capital Guwahati led the Indian government to shut down the internet in the state on Dec. 11.

Citizens here are also concerned about the controversial National Register of Citizens (NRC), which requires people to produce documents of ancestry to be enlisted as Indian citizens. This exercise, undertaken by prime minister Narendra Modi’s government in Assam between February 2015 and August this year, was meant to “throw out infiltrators.”

The final list of citizens, published on Aug. 31, excluded nearly 19 lakh residents of Assam, including Hindus.

Ever since, India’s home minister Amit Shah has hinted at the possibility of a nationwide NRC. Shah referred to “illegal immigrants” as “termites” in April, and the citizenship act is now being seen in the context of the planned nationwide NRC.

By all accounts, the NRC in Assam only seems to have deepened the divide between the different cultural groups in the state, bringing back memories of the unrest of the 1980s. This was a time when Assamese-speaking residents of the state feared being overpowered by Bengali-speaking Bangladeshi immigrants after Bangladesh’s liberation in 1971.

Some commentators have equated the NRC with ethnic cleansing, much like what the Rohingya Muslims of Myanmar faced. The fear is that a nation-wide NRC could only prove disastrous where residents could be profiled on the basis of their religions and stripped of their citizenship overnight.

Citizenship Act and NRC

Protestors believe that the exclusion of Muslims and a nationwide NRC are products of the same school of thought. The paranoia against “outsiders” and “infiltrators” rings strong in both narratives, though by the government’s own estimates, the citizenship act will help a little over 31,000 people.

Given the exclusionary privileges, those protesting believe that the new law will only be used to polarise Indian communities, especially Hindus, against Muslims. On Dec. 11, just before the Citizenship Amendment Bill (CAB) was cleared, over 700 activists, academicians, and filmmakers wrote a letter to the Indian government expressing grave concern over these two proposed laws. “For the first time there is a statutory attempt to not just privilege peoples from some faiths but at the same time relegate another, Muslims, to second-rate status,” they wrote.

The new law, they wrote, also went against the tenets of the Indian constitution. “The CAB is at odds with Constitutional secular principles and a violation of Articles 13, 14, 15, 16 and 21 which guarantee the right to equality, equality before the law and non discriminatory treatment by the Indian state,” they wrote.