Inside the Chinese dating apps exploiting the loneliness of India’s men

“Find a girlfriend in a week,” said the ad. Raju Ansari, a shopkeeper in Delhi, was on Facebook to beat nighttime loneliness when that promise popped up on his timeline. The smartphone app’s logo flashed a heart, half blue and half red. Love was in the very name of the app being advertised: L’amour.

“Find a girlfriend in a week,” said the ad. Raju Ansari, a shopkeeper in Delhi, was on Facebook to beat nighttime loneliness when that promise popped up on his timeline. The smartphone app’s logo flashed a heart, half blue and half red. Love was in the very name of the app being advertised: L’amour.

Ansari was hooked. The download button on his phone took him to Google’s Play Store, where L’amour appeared to be heavily recommended, with a 4.2+ rating, 10 million-plus downloads and sixth position among the “top grossing” apps.

The promise kept building. When he opened the app, he was greeted by photographs of women so attractive, he would have been thrilled to hear from any one of them. To his wild surprise, he heard from several. Their messages began pouring in the moment he signed up, each one more flirtatious than the last.

“I have never chatted with anyone on a dating app before.”

“Are you the one I am looking for?”

“Say something.”

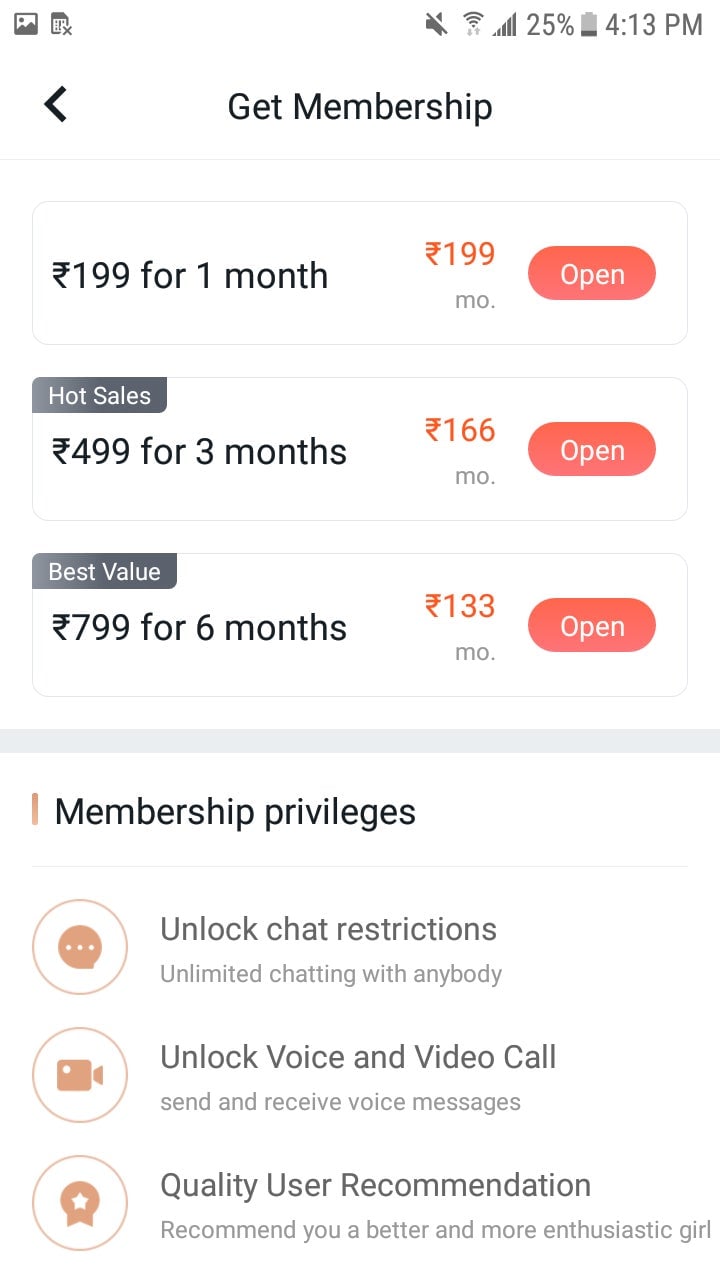

He tried to respond, but the app informed him that he first needed to buy a subscription for Rs199—which he did right away. As a paid member of L’amour, he was now able to respond to messages, but he noticed, strangely, he was no longer getting as many as before. He was, however, now flooded with audio and video calls from women.

“Ayesha very interested, and she wants to talk to you.”

“Mia is calling, don’t miss out on her.”

“Ipshita is inviting you to a video call.”

He couldn’t answer any of them, even though his subscription was supposed to “unlock chat restrictions” and “unlock voice and video calls.” Now, he says, he was being told by the app that to receive a call on L’amour, he would have to pay more.

For another Rs350, he could buy 1,599 diamonds, the app’s internal currency, and start video chatting.

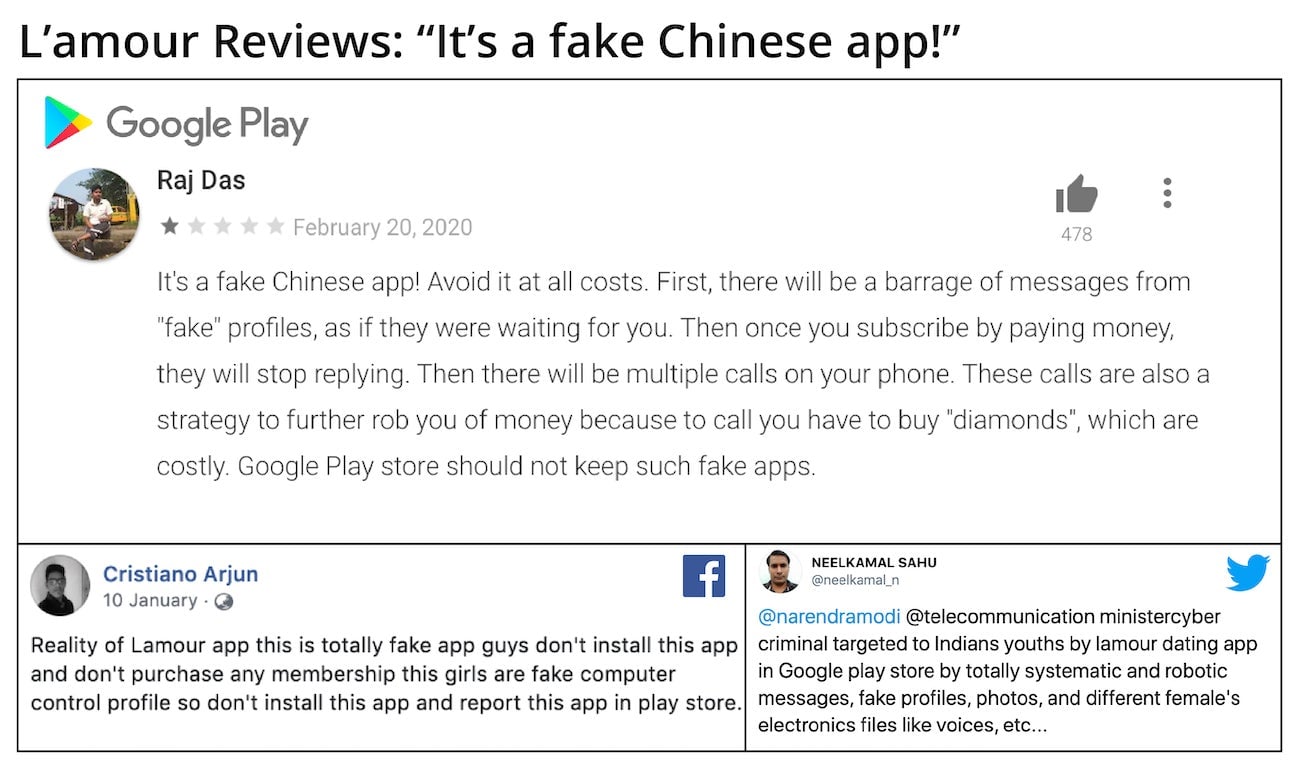

Now wary, he looked up reviews of L’amour. The internet is filled with them, most of them containing the word “fake.”

“This is totally fake app guys don’t install this app and don’t purchase any membership this girls are fake computer control profile so don’t install this app and report this app in play store.” (Facebook)

“Google, please keep a sharp eye on L’amour app. It’s totally fake app. It’s only eat peoples money on the name of love. Please remove from play store. It’s nothing more than manipulation” (Play Store)

There are positive reviews of L’amour as well, but many appear suspicious. The same language is often repeated across multiple reviews, and in some, the praise doesn’t seem relevant to the features of L’amour.

Ansari hasn’t opened the app since. “Bakwaas app hai (It’s a stupid app),” he said.

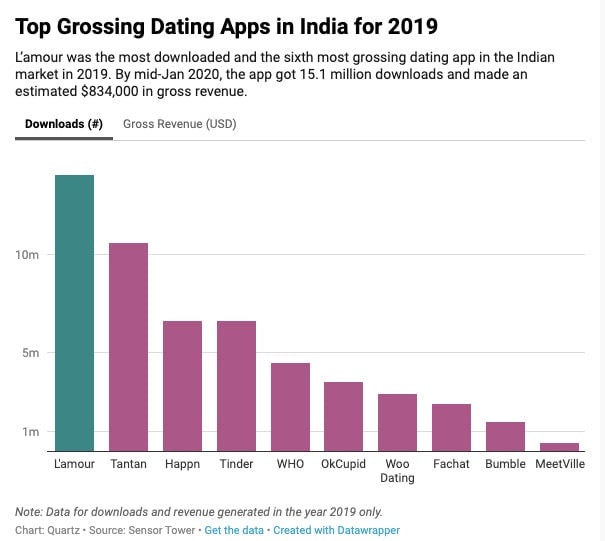

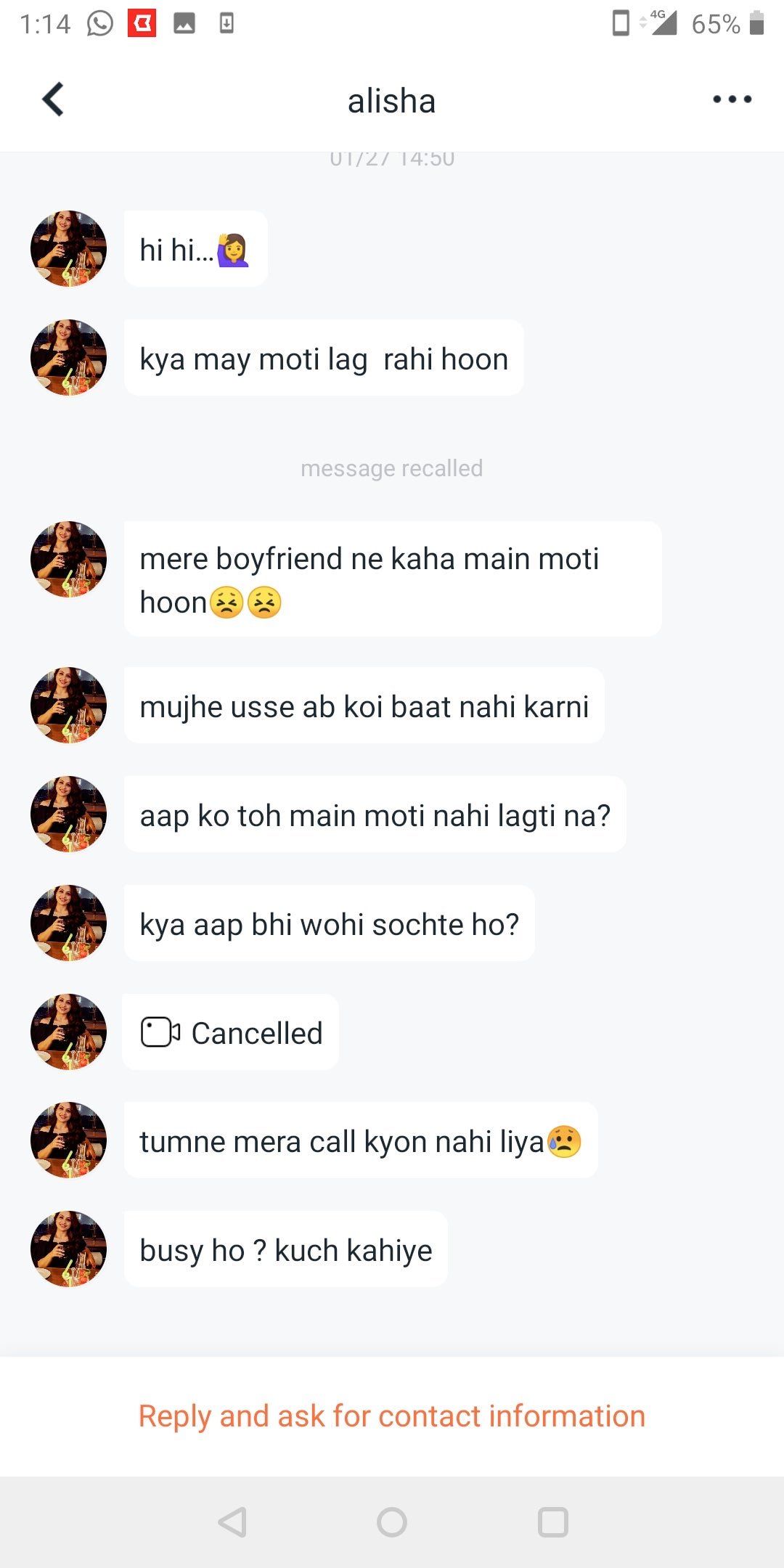

L’amour was the most downloaded dating app in India in 2019, according to Sensor Tower, an app-industry research and analytics firm. It was launched in June, and through December, around 14 million users had installed it. Tinder was downloaded by 6.6 million over the same period.

The majority of its users are men, and interviews suggest many of them have had a similar experience. It often begins with the men coming across an online ad for the app. The racy messages dry up after they subscribe. The sexy photos keeping them awake are sometimes blatantly stolen from the internet. And, as Quartz’s reporting shows, the women who appear on the audio and video calls that the men can access once they buy diamonds are, in fact, often trained and paid by the app to con men into exhausting their in-app currency.

Asia Innovations Group, a Beijing-based company that owns L’amour, denies the presence of bots and paid female users on the platform. Our reporting suggests there’s more to the story.

“Predatory apps”

L’amour isn’t the only app to exploit the rich market created by the extraordinary imbalances that define the Indian dating scene, with its uneven numbers of men and women in general, on the internet, and on dating apps.

India’s dating market is flooded with apps like L’amour, where users must pay at every step and still never wind up with a date. Most of the apps are owned and run by Chinese companies that operate in India through a network of local employees, partners and payment gateways.

“These predatory apps have captured the market between matrimony and porn,” said digital anthropologist Payal Arora, a professor at Erasmus University Rotterdam and author of The Next Billion Users.

In January 2020, 14 of the 20 top-grossing apps on Google’s Play Store in India were offering dating and “chatting.” Tinder was number one on the list, and Bumble was 25. The apps LivU, L’amour, and Tumile ranked third, sixth, and eighth, respectively.

Each of the apps follows the same model. Every second of exploration is charged. The more time they spend, the more tempting the possibilities.

“What they want often is some girl asking about their day: How was it? What did they eat for lunch? It is the everyday mundaneness of downloading your day to someone that makes your day count,” Arora, the anthropologist, said.

At some point, however, users realize that getting a girlfriend in a week is something that typically only happens to men in Hollywood movies and L’amour ads.

“I have done many things in life, but never made a girlfriend. Just never found the time for it. When I saw this app, I said to myself, ‘Let me see what’s it like to have one, to do time pass with her,” said a man who goes by ‘Goswami ji’ in a YouTube video dedicated to fellow seekers.

He quickly comes to the point: “Just how many girls do we send friend requests to on Facebook? It’s rare for even one in a hundred to respond to our messages. And here are girls asking you left, right, and center if you also want what they want. You really think a girl is asking you that?”

He continues: “Then you get these voice recordings, with girls asking if you will watch a movie with them or if you will go shopping with them, and all the girls sound the same. The moment you upgrade your package on the app, they all vanish. These are not real women. The people who run these apps are playing with your brain.”

A tried-and-tested model

In 2015, Harinder Kumar, who goes by Harry, was a largely bored man who traded stocks for a living. Then he found BIGO Live and got hooked to the live-streaming app that boasts over 60 million Indian users.

The following year, he converted his pastime into a business plan. Speaking to insiders in the domestic app industry, Harry learned that the “hosts” on the platform weren’t always random individuals broadcasting their thoughts and talents from their bedrooms. These were people hired by the company, often through partner agencies, to boost the quality and variety of content available for the viewers. So, he left trading stocks and started hiring streamers for BIGO Live, owned by the Chinese conglomerate YY Inc.

The deal was simple: Harry kept 5% of the amount BIGO paid the hosts he recruited. For Harry, it was good business and great fun: “Kaam to tha, craze bhi tha. Maza aane laga. (It became my work and my passion. I began to enjoy the experience.)”

Today, BIGO LIVE has a network of 10,000 paid broadcasters in India who can make anywhere from Rs10,000 to Rs100,000 in a month.

YY Inc is, of course, only one among hundreds of Chinese companies coming to India to monetize the needs of a multitude of first-time internet users—“the next half billion”—in fields as diverse as social media, online learning, and short-term loans.

“Every day at least one Chinese company approaches us,” said Dhiraj Sarkar, a director of Dokypay, a payment gateway that serves a variety of Chinese apps operating in India.

Technology company Asia Innovations Group (AIG) is one of them. Its CEO is Andy Tian, an MIT-trained computer engineer and ex-Googler whose LinkedIn profile says he “helped to bring Android to China.”

Founded in 2013, AIG has publicly stated that it aims to become the “largest global social entertainment platform.” So far, the company has 14 offices, including in Jakarta, Cairo, Los Angeles, and Gurugram. It has raised four rounds of funding since its inception and is currently valued at over 2 billion yuan ($290 million), according to its website.

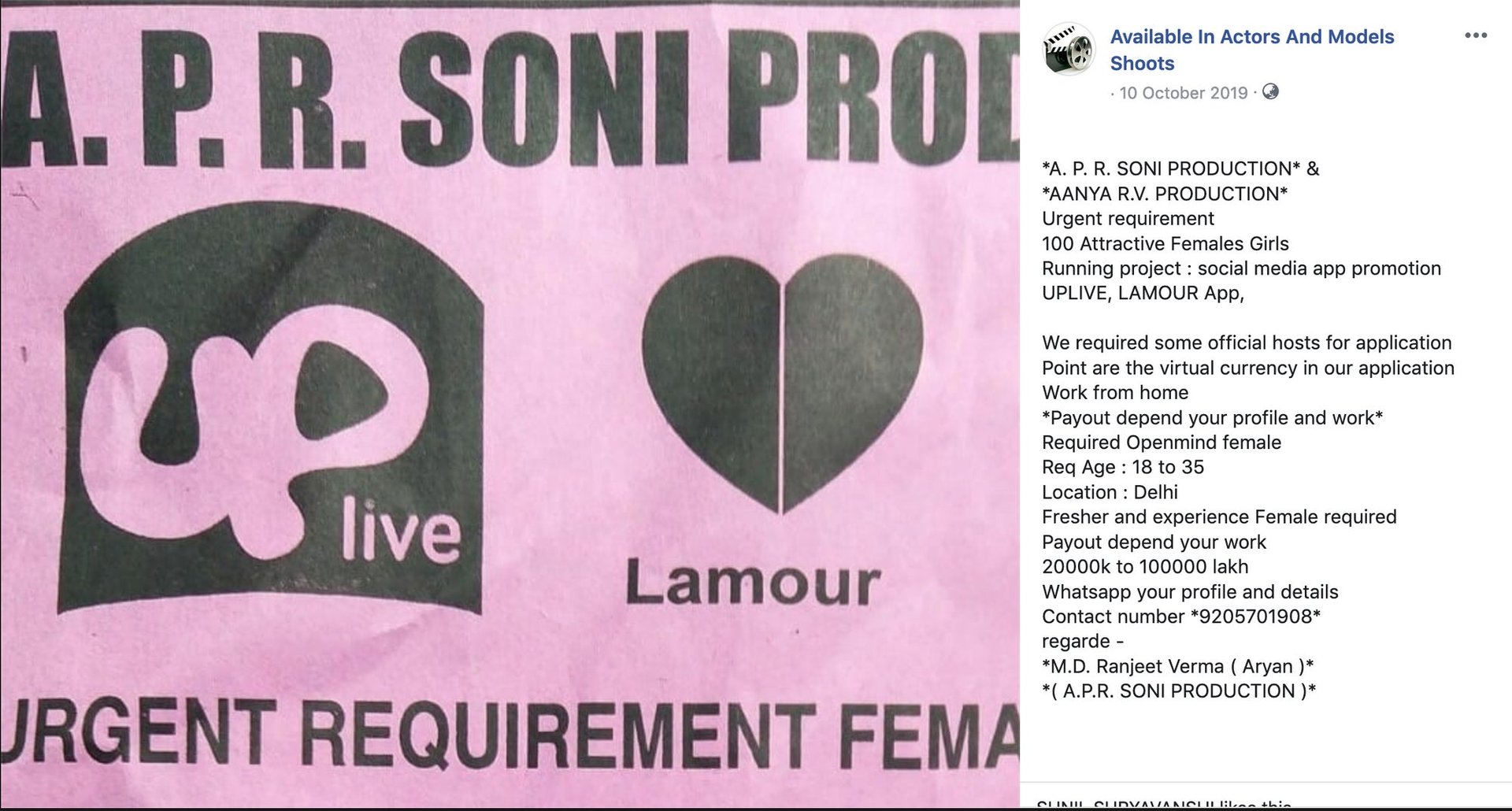

AIG claims to have over 100 million users for its various tech products that span dating, live streaming, and gaming. In 2018, AIG entered the Indian market. To roll out its local operations, 29-year-old Harry says AIG sought him out. First, AIG launched a live-stream app modeled on BIGO called UpLive. The company asked Harry, who was still working independently, to set up an office in Gurugram.

Later that year, he said, he was hired by AIG as a “talent specialist.” By this time Harry had provided his services to two Chinese companies running live-streaming apps and knew about the challenges they faced in the Indian market. In December, he left AIG to start Sonacon Entertainment, a talent agency.

Today, with a staff of over 40 people, Sonacon claims to have hired nearly 2,000 live streamers, almost all of them female, for more than 15 Chinese apps. “Men can’t generate revenue in live-streaming,” Harry said.

In June 2019, AIG launched L’amour in India and commissioned Sonacon to recruit women and train them on how to behave on the platform. The goal for these women isn’t to find a date.

Meet thousands of beautiful girls

From its inception, L’amour wasn’t an app meant to cater to the relationship needs of privileged Indians in the country’s biggest cities, like Mumbai and New Delhi—“Tier 1 cities” in marketing parlance.

“Online dating in India is now just for the very elite. There is a huge vacuum for the users in tier 2, 3, 4, 5 cities, and villages. Our goal for L’amour is to enable quality interactions between males and females of any social status, for the 95% of the mass market, not just the elite,” Tian, the CEO of AIG, said via email. “To ensure that whoever female users interact with are of higher quality, we request membership before that interaction. So far, this seems to have high appeal.”

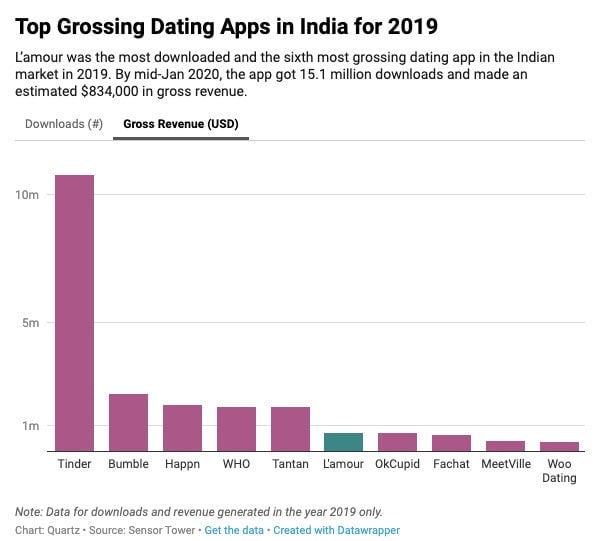

To reach potential customers, the company bombards social media platforms with ads for the app. The “Lamour India” Facebook page had around 1,000 active ads in the first week of February, according to data from the Facebook ad library.

The ads mostly target men.

“Do you not have a girlfriend? Make one now.”

“Meet thousands of beautiful girls, only on L’amour.”

“Find a girl to date now.”

That ad strategy goes against the tried-and-tested wisdom that the success of a dating app depends on the number of women users. Fewer women on the app typically means fewer opportunities for men to find a date, which means lower engagement and less profit for the company.

But this rule doesn’t hold if a dating app’s business isn’t, in fact, tied to dating. There isn’t a lot of evidence that the Chinese dating apps Sonacon partners with are effective at helping people find love or sex. Instead, these apps seem to be exploiting their desire for it.

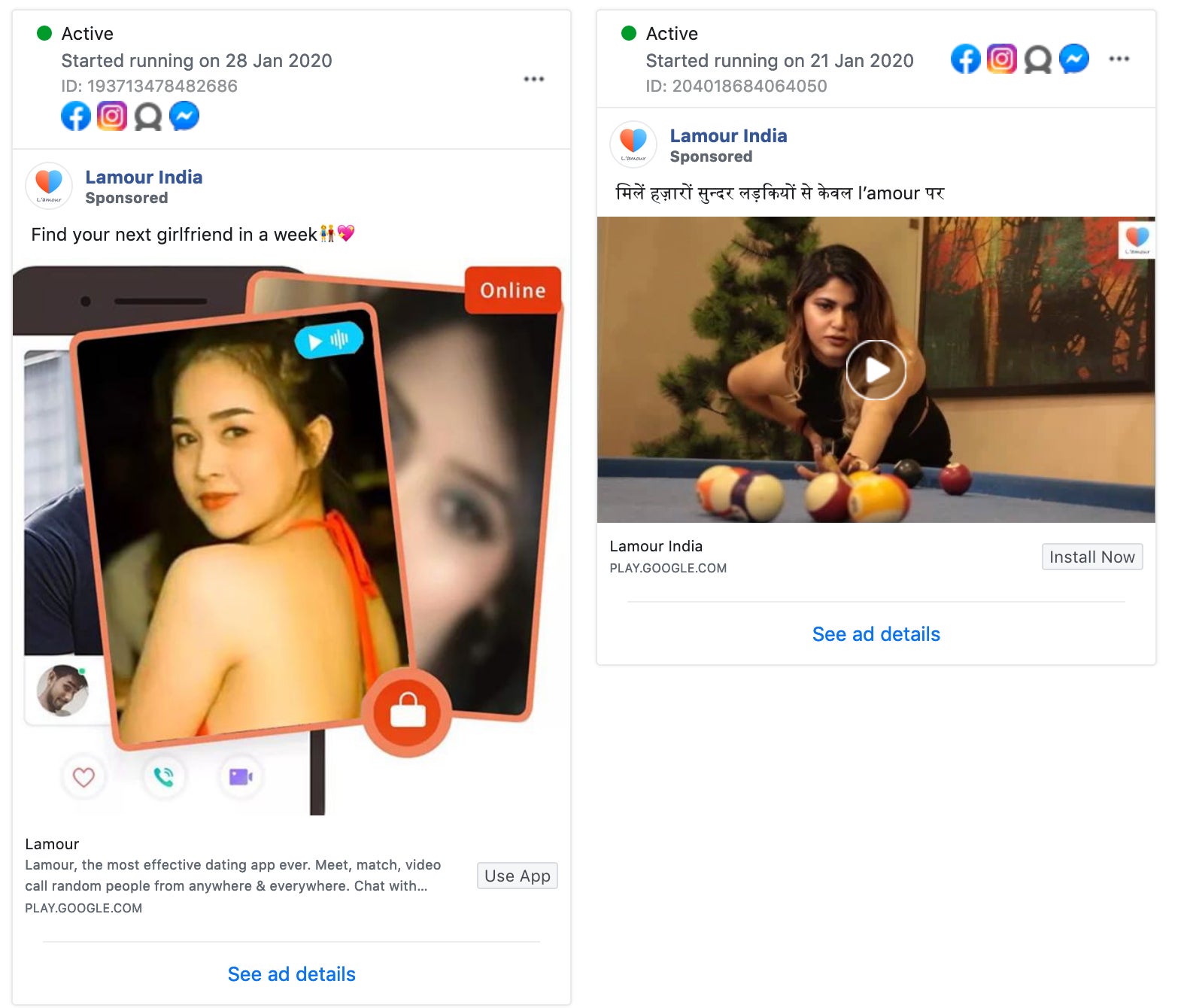

The model already has worked in China. It usually starts with bots, but their utility ends when free users turn into paid members, because the AI powering the bots often isn’t advanced enough to engage the users beyond the initial hook. It is quite easy to identify the messages as machine-generated because they are repetitive, come in bulk, and state the oddest things.

Imagine being a straight man on an Indian dating app where any time you enter the platform you are notified that dozens of women are typing messages to you. (Mysteriously, based on our testing, no one messages you while you are not on the app, even if your profile has been active.) Once they have started typing, they don’t seem to be able to stop. Some of them tell you they find you cute even if you haven’t put up a profile picture. Many of these messages are framed as questions:

“Do you watch porn?”

“Do you like sex?”

“Do you like spicy food?”

They go on and on in this loop no matter what you choose as the response from a set of fixed options: YES/NO, GOOD/NOT BAD.

Tian didn’t acknowledge the presence of bots on L’amour. “The women are real, messages are also real as well,” he said via email in response to our questions. He also said AIG does not work with Sonacon but that the agency has approached AIG in the past “as they have approached many dating apps that we know of.”

But two ex-AIG employees disputed Tian’s assertion.

“The bots are developed in-house,” a former AIG employee confirmed on the condition of anonymity. “Users don’t know about it. Many who have a lot of free time like to chat with the bots.”

“Fifty percent of the messages on the app are sent by robots,” said another ex-employee who didn’t want to be named either. “Indian employees make Excel sheets with messages containing attractive words and send them to the product team in China, who program it into the app.”

“When you get unwarranted messages from the bots, it could be brought under the ambit of Section 66 and 43(i) of the IT Act,” said Pawan Duggal, a Delhi-based cyber lawyer, “It is clearly coming to my device without permission. It’s a bailable offense: three years in prison and 5 lakh rupees fine.”

Duggal said it’s also prosecutable under the Indian Penal Code. “If you are able to show that messages sent by bots are blatantly false–means being said to be coming from a girl but effectively coming from a bot—it can definitely be said they are forged electronic records, that have been created for purpose of cheating—that can come under section 468 of IPC: non bailable, seven-year imprisonment, and fine.”

Once the bots have pulled the men in, they are flooded with phone calls from prospective dates, but they can only pick up these calls if they buy the in-app currency.

To make these video calls, L’amour needs real women, at least some of whom are hired for the job by “talent specialists” such as Harry. This is where the line between dating and live-streaming blurs. But Harry points out two key differences.

“On live-streaming apps, users can watch content for free, and only if they wish, they buy in-app currency and send gifts,” he says. “But you can’t date for free. You have to pay to date.” Also, a live-stream is meant for the viewing public, while a video call on a dating app is a “one-to-one broadcast.”

Other industry insiders view these dating apps as being premised on “one-on-one coin collection.”

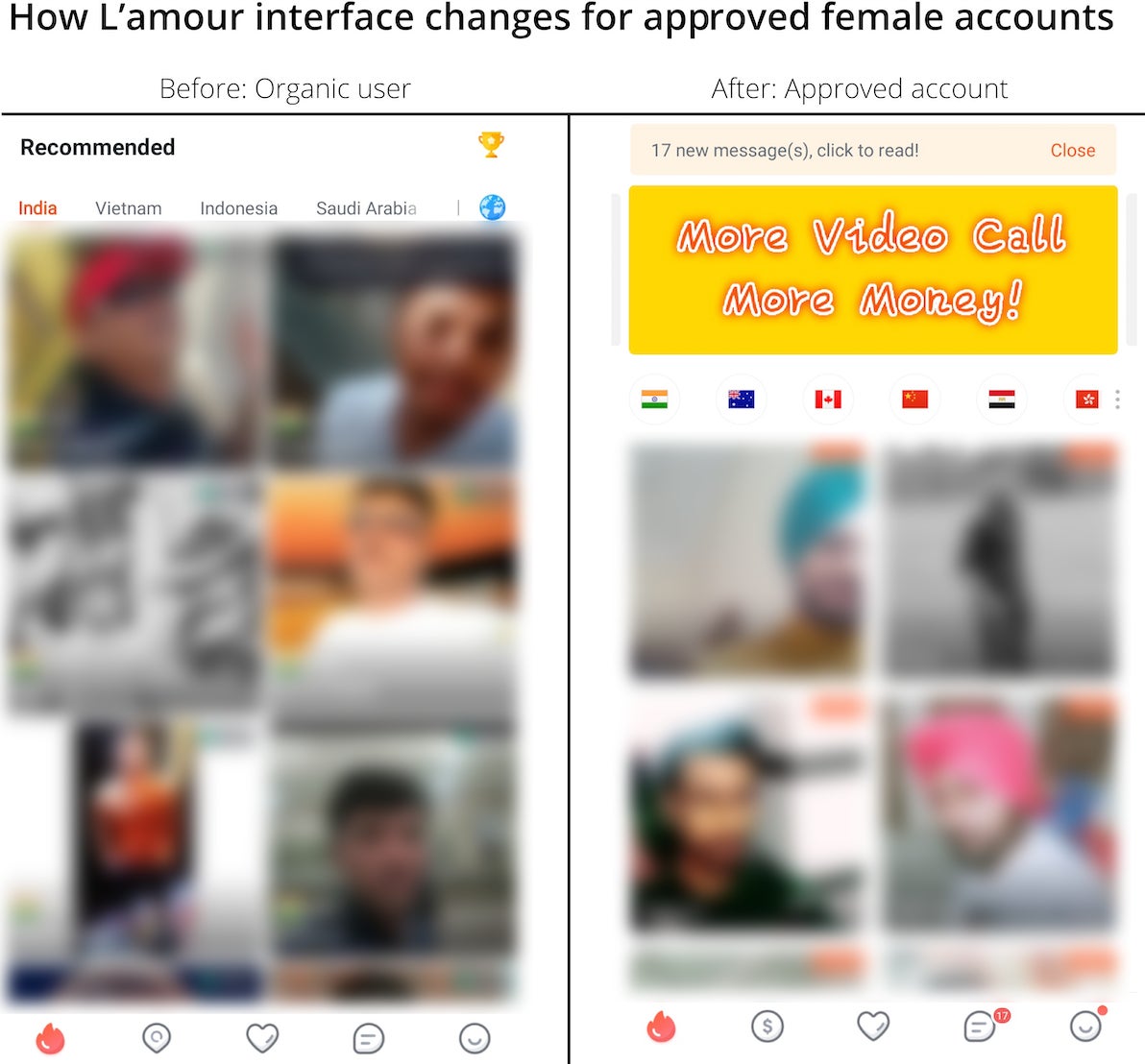

“The female hosts collect coins every time they interact with a man. These women are properly trained after their accounts have been approved by the app. They earn a fixed number of coins for every minute of video or text encounter,” said the ex-AIG employee who worked in talent acquisition. This description was confirmed by our own experiences. He pointed out that there’s little for women to do on the app if they aren’t treating it as an income source. While it’s possible that some women are using these apps to get dates, between December 2019 and March 2020, we tried several Chinese dating apps popular in India, including L’amour, as both male and female users and were able to replicate what others described.

As a male user, we paid hundreds of rupees to buy a membership, to chat with what seemed to be prolific robots, and to receive video calls from real women who seemed keen to prolong the minutes. As female users, we signed up but no man reached out or even responded until our account was “approved” by the apps and set up for business.

Things changed dramatically after we found the recruitment ads for L’amour, contacted the agents, followed their instructions on how to create a profile (which required us to send the agent a screenshot of the account for approval), and became an earning user. Hundreds of active male profiles appeared all of a sudden. We were no longer encouraged to find “love all over the world” but reminded “more video calls, more money.” The coins began to show up in a bow-tied box supposed to store our “daily earnings.”

Tian denied any possibility of L’amour training or paying women directly or indirectly to interact with the men. “This statement is completely untrue. The women users are organic users on the platform,” he said. “Users on L’amour choose to interact with each other. That’s the core appeal of L’amour, that you can truly find women to talk to.”

Not every Chinese dating app in the Indian market directly offers dating. Many are placed on the Play Store under categories such as “lifestyle”, “social,” and “communication,” but each sells the promise of love or sex at one point or another. It’s too lucrative a market to miss out on. In 2018 alone, dating-related searches in India went up by 40%, according to a report by Google.

At number three in overall “top grossing” apps and number one in the “social” category is an app called LivU, on which you can “meet new people and video chat with strangers.” If you are an Indian man using the app, you will find yourself randomly matched with a woman whose profile identifies her as Korean, Libyan, or French, and you can even call her for free. But a few seconds into the video call, you get a message from the app asking you to pay if you “still want to chat.”

At number 10 with over 100 million downloads is Hago, owned by YY, which invites users to “play games (Sheep Fight, Knife Hit, Brain Quiz) and make friends.” The app is not marketed as for dating, but once you are on the app, you get a cascade of notifications from women asking if “You are the one I am looking for.”

On ParaU (number 13 in the app ranking), you can swipe to “video chat and make friends,” but the ads that men are shown inside the app are about finding “your perfect woman right now.” ParaU also asks men if they are “open to try new things in bed” and offers them a range of female body types (“slim/fit/plumpish”) to select from as soon as they log in.

LivU, Tumile, ParaU and Hago did not respond to requests for comment.

We found that the women users of these dating apps are given clear instructions about their mandate in advance of them creating profiles, when they’re first recruited to the platforms.

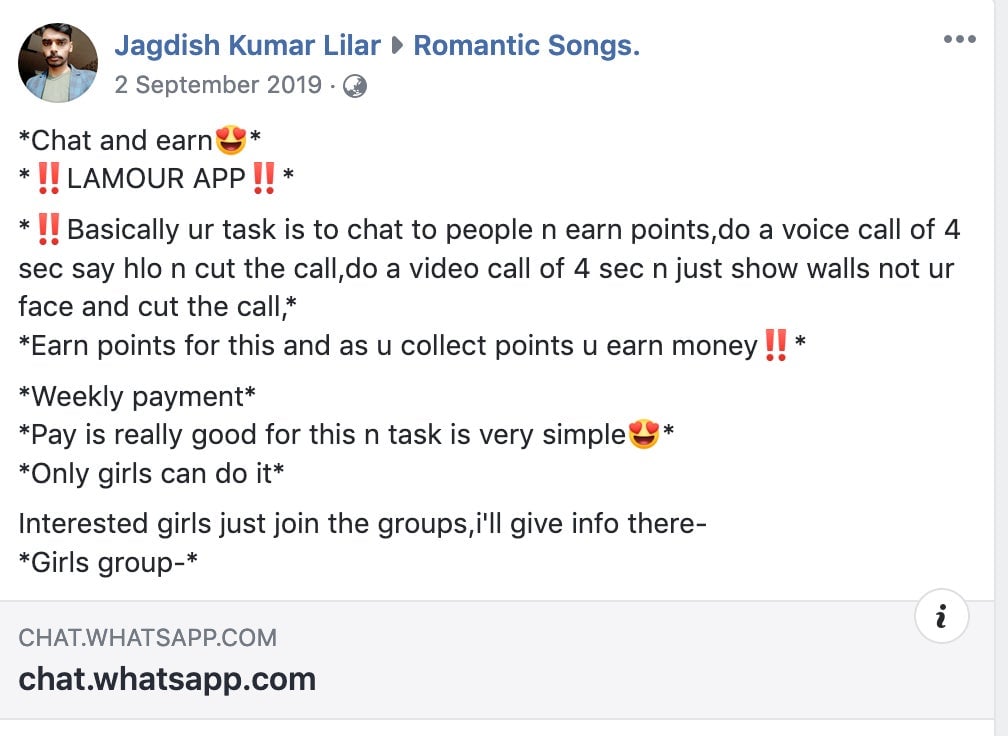

Consider this Facebook advertisement posted by Jagdish Lilar, an independent recruitment agent for dating apps.

“Basically your task is to chat with people and earn points, do a voice call of 4 seconds, say hello and cut the call; do a video call of four seconds and just show walls, not your face and cut the call. Earn points for this and as you collect points, you earn money.”

Lilar said he has a vast pool of women workers who he manages via WhatsApp. A former AIG employee didn’t doubt the claim. “I know of at least a hundred agencies who manage more than 500 women each,” the AIG ex-employee said.

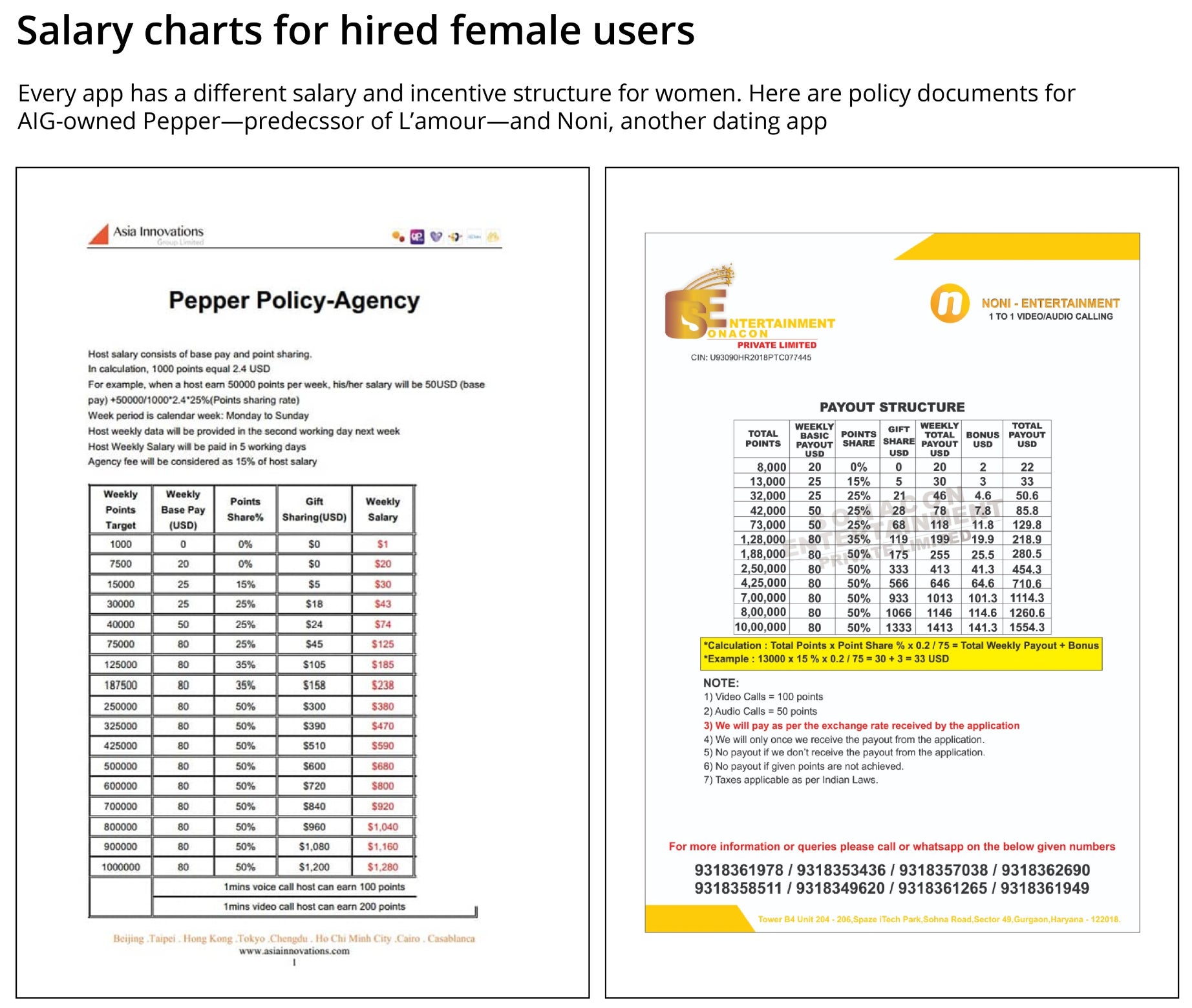

Some of the apps require the women to make a fixed number of calls every day, while some pay according to the hours they spend on the calls. These stats feed directly into the women’s profiles, where they can see their income being updated accordingly.

One woman, who goes by Ruhi online, makes and receives video calls on fake dating apps whenever she can and from wherever she is, whether in the office or at home or on public transport. “I spend about two and half hours a day on the calls, and one call can be 10 seconds or 10 minutes,” she said.

She said she used to be active on L’amour until recently; now she is earning a salary from a Hong Kong-based app called Yaar, which claims to have enabled “19,535,433,586 matches” so far. Ruhi said she isn’t paid $26 a week to pair up with the men but to prise out their coins.

Yaar did not respond to questions we sent via email.

To get a monthly salary of Rs10,000 from Yaar, she said she needs to appear on at least 4,200 video calls in 15 days. She also earns a salary from Sonacon where she finds and recruits female users for fake dating apps.

“Every day we have a Chinese or Korean company coming in to seek a collaboration,” she said.

Her instructions to the women are the same no matter what the app: “You can use a fake name. You can upload a fake photo. Pick anything from Google. Just collect six photos of the same person and keep using them on different platforms. Do the same for video. The better the display picture and video you upload, the more calls you will get.”

These photos and videos can belong to anyone on the internet; it could be someone’s Facebook profile picture or a viral TikTok clip. It’s easy to spot celebrities while scrolling through profile photos and video on any of these apps.

The profile photo of “juicy orange” on the Chinese dating app Noni actually belongs to television actor Arishfa Khan. The “cute videos” section of many Chinese platforms, from LivU to TuMile, are flooded with clips lifted from short-video apps like TikTok, VMate, and Likee. One of the women video-chatting with men in the Facebook ads of L’amour is TikTok star Jannat Zubair.

“All the female profiles are uploaded by users,” Tian said, adding that “like all social apps, we do not, and cannot control where these users get their photos…However, like all social apps, if we get complaints on content, or photos, we investigate and if the content is inappropriate, we take the account down.”

Ruhi likes to keep changing her profile images. One day she is an unknown Indian woman and the next day she is a Chinese film star. The only thing she urges every woman to add accurately to their dating app profiles is their bank account information, so they can receive their incomes without any confusion. Earning that money, however, isn’t easy.

One has to keep at it, she said. “The men will be texting with you, but you got to goad them into calling you so that you complete your needed points for the day. You have to really drag each conversation. Five minutes can go by if you simply keep asking, ‘What do you do? Where do you live?’ Even if it’s a one-second call, his 70 coins are gone. You can also ask them to send you gifts.”

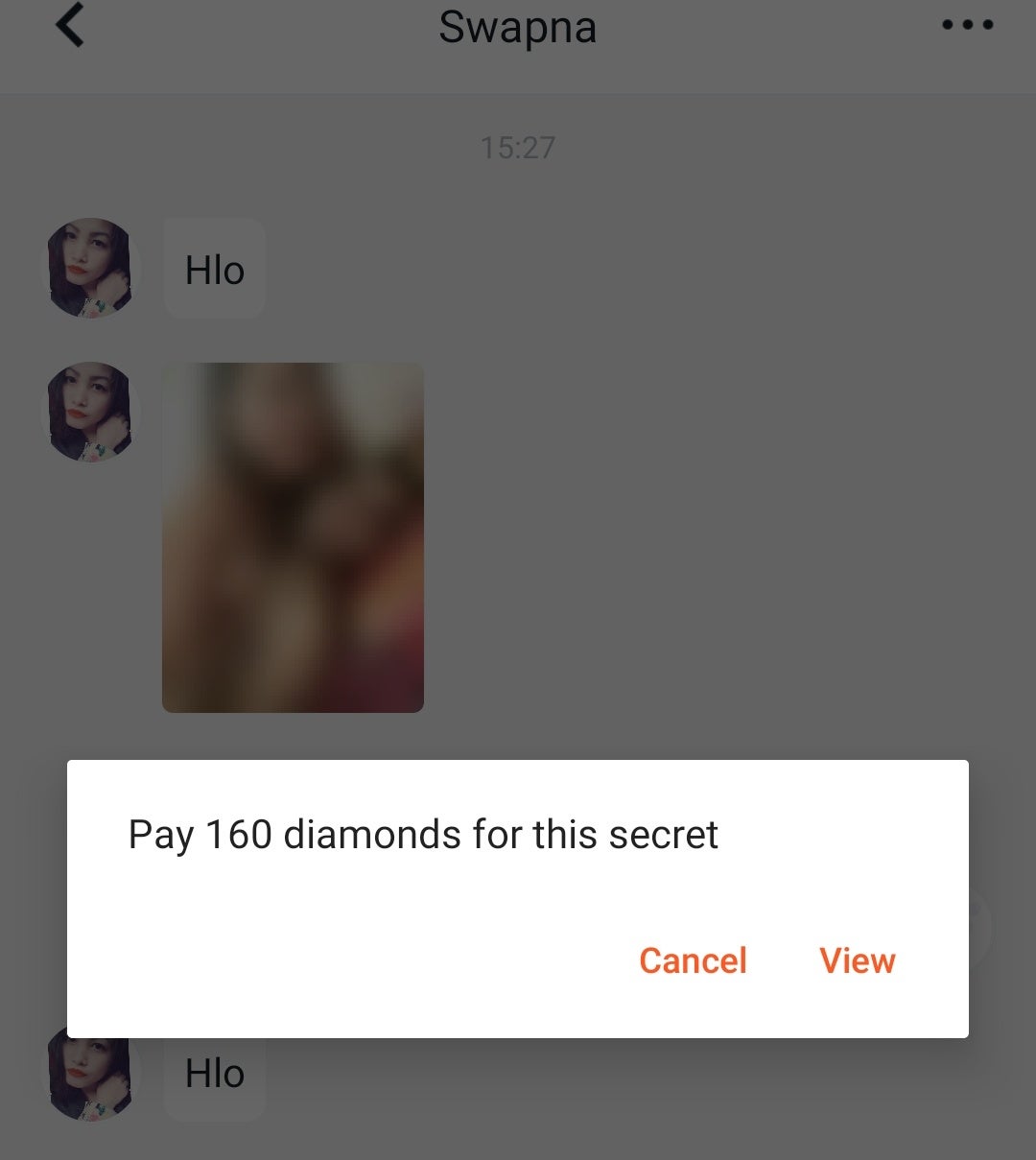

L’amour turns real money into diamonds for men and coins for women, and hides the exact value of the transaction behind fictional valuations of in-app currencies.

While women are paid around Rs2-4 per minute for video chatting, men have to spend significantly more, even up to Rs70 per minute on L’amour. The exact amount varies with the design of the application, but roughly, women make less than 5% of what men spend to talk to them.

“I know girls who sit at home all night making video calls alongside their younger sisters, older sisters, even mothers,” said the ex-AIG employee.

The cyber lawyer Pawan Duggal said there exist enough loopholes in Indian law to cast the presence of hired female users on these dating apps in a grey zone. “It’s not the company that’s calling the client. [They can say] the client is getting some demand fulfilled from the service [by the women] … Even if the cases are made out, it is such a tall order to get the police to register FIR. Ultimately there is no practical remedy for the consumer. They have been left out in the lurch.”

Where’s the money?

This financial model wouldn’t be successful without a frictionless payment experience. To that end, the Chinese companies have set up payment gateways to ease their way in different markets with varying financial regulations and mechanics.

Every time a man makes a payment on L’amour, it goes through a gateway called DokyPay, whose parent company, LinkYun Technology, came to India in 2018. Nearly 80 of LinkYun’s 200 employees are based in Gurugram. The rest are scattered across Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Vietnam.

“As a payment gateway, we are suited to their [Chinese apps] needs. We don’t have lengthy processes like Paypal,” said Dhiraj Sarkar, one of the directors of DokyPay in India.

Apps like L’amour play the volume game: a mass-market product, a small transaction price, and a high number of value-conscious customers. According to data from SensorTower, L’amour made $0.8 million in the Indian market from June 2019 to Jan 2020.

“At least 50 dating-related apps from China are running in India,” Sarkar said. There is no evidence that Dokypay executives know about the fraudulent aspects of the dating apps it partners with.

Sleaze is integral to the business, though. On L’amour, the men even receive strategically blurred images of women and are asked by the app to pay in order to have a clear view. The app code shows that if a man views a “secret image,” the woman sender gets paid for it.

The women are instructed to treat sleaze as a professional hazard. As Ruhi explains to her new recruits: “On these apps, people say naughty things. For example, kuch dikhayegi (Will you show something)? You mustn’t feel bad. After all, these sorts of things are said to us by men even walking down a road. If you are okay with it, you can make a lot of money.”

Many of the men who come to suspect they’ve been conned just go on with their lives, considering this another failed attempt at interacting with a woman online. But thousands of others go online to leave reviews or demand a refund. YouTube is a favorite with many of them.

The most popular video review of L’amour has 1.2 million views as of this writing. It is titled: “How to use Lamour app for free | Lamour app fake or real.”

“Friends, don’t pay any money in this app because it is not genuine,” the YouTuber tells his viewers as he takes them through every step of his experience. “Even if you pay, there is no guarantee that you can send text messages or do video calls,” he says, stressing the point that he speaks from firsthand experience. “You pay any amount of money, but you will not get to talk. This is a fraud dating application.”

AIG is aware of the complaints. “Complaints with dating apps are common, and all dating apps experience them, especially Tinder,” Tian, AIG’s CEO said.

Around 30 of L’amour’s staff of 50 people in Gurugram work in the customer support team, a company employee said. They sit in a separate office and work around the clock to address the 1,500 to 2,000 complaints they receive daily, according to a current and a former employee of the company. The technology team is entirely based in China.

The AIG employee in Gurugram, who works on the product, doesn’t think the app is misrepresenting its offerings. He blames the users: “Many of them call because they are not sure why they have to pay for things after buying a subscription,” he said. “If users don’t find enough profiles or don’t get enough calls, then they complain to Google.”

While reporting this story, Quartz came across an entire service industry of low-wage workers generating fake reviews for various apps. Mukesh (name changed), a college student, runs a review management service. To generate business, he sends cold emails to app owners to inform them of his company. He claims to have a network of over 6,000 people he manages through WhatsApp, who write fake reviews from their own devices.

“Not just review: five-star rating + comments related to your application,” he writes in his emails to potential clients. He charges an app Rs15 per review. For dating apps, he ensures that more than half of the reviews are posted from “girl name IDs.” There is no evidence that he has ever worked for AIG.

In response to a detailed questionnaire sent by Quartz on the presence of fraudulent dating apps on the Play Store, a Google spokesperson said that the company takes “security seriously and Google Play automatically scans for potentially malicious apps as well as spammy accounts before they are published on the Google Play Store.”

Fraud is never far from any dating service with a mass reach. In September 2018, consumer protection authorities in the United States filed a lawsuit against Match.com—parent company of Tinder and OKCupid—alleging that the apps “exposed consumers to the risk of fraud” by “allowing fraudulent accounts to operate on the dating services.”

Messages like “You caught his eye!” and “Someone’s interested in you!” which were meant to convert free users into paying members, came from false profiles, authorities alleged.

“Online dating services obviously shouldn’t be using romance scammers as a way to fatten their bottom line,” the FTC said, a claim that Match declared “completely meritless.”

In China, the reported cases are even more serious. In January 2018, dating apps run by 21 firms were shut down and more than 600 suspects were arrested following allegations of fraud to the tune of more than $150 million targeting thousands of customers.

“Some of the apps claimed customers could chat with ‘sexy girls’ online, but clients found themselves messaging and receiving answers from artificial intelligence computer programs instead,” the New Express reported.

When these apps fold, they often return with a different name or pitch.

“Most Chinese companies increase their rank on the Play Store by paid traffic, reaching users by heavily spending on ads. Then they realize there is no retention, so they burn out cash and go away,” said Himanshu Gupta, a former executive of WeChat India, owned by Tencent, a Chinese technology company. “That’s why you will find many Chinese apps in the top 100, but the names on that list keep changing.”

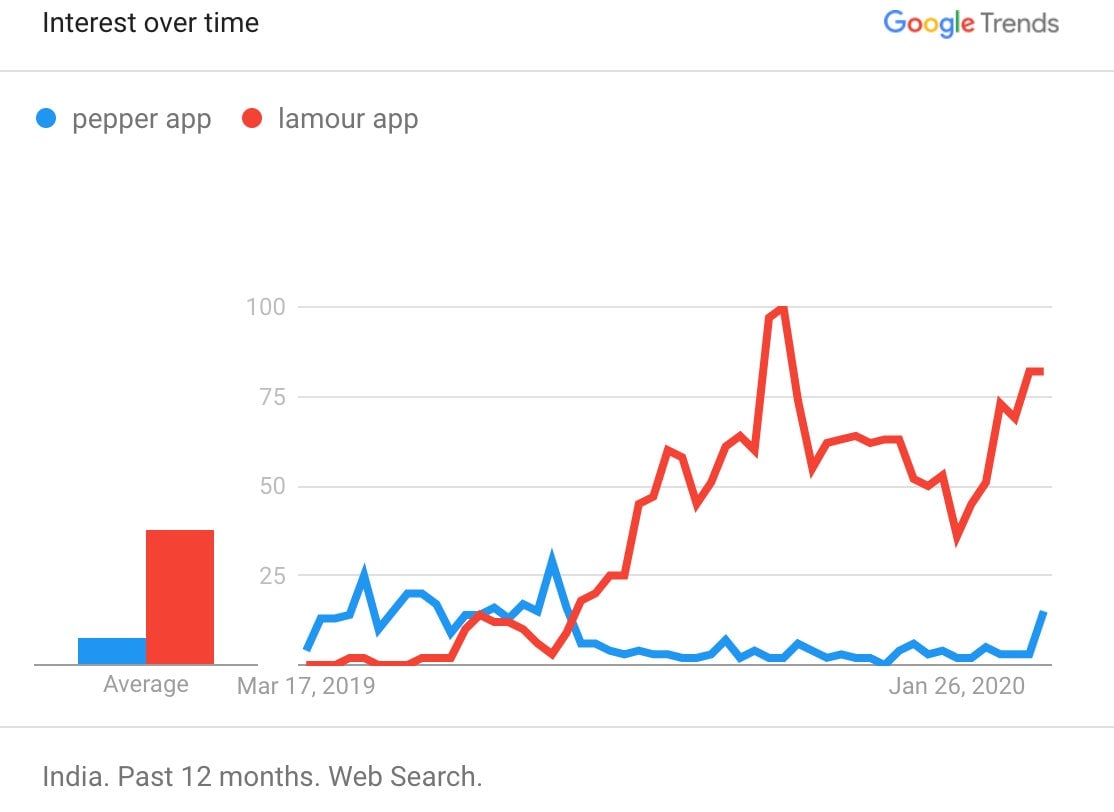

By late 2019, when L’amour became wildly popular, many similar apps had already gone off the market and many others were rising up the charts. The YouTuber who warned his viewers to stay away from L’amour ends his video by recalling a similar app from the recent past: “If you would have used the Pepper dating app, that was the same as L’amour.”

What he likely didn’t know is that Pepper was also run by L’amour’s parent company—AIG. (We downloaded an archived version of the Pepper app and tested it to find that it is in fact a copy of L’amour.)

Pepper is only one of the recent dating apps to look like a clone of L’amour’s. Others bearing an eerie similarity are Sweety (earlier called Barfi) and DPA. Started in December 2018 and August 2019 respectively, DPA and Sweety have both since crossed 1 million installs. Not only is their interface common, but even the apparent bots sending messages on these platforms are the same.

“Tia” is active on three of these apps, Pepper being off the market, and begins each conversation with the same question—“Do you watch porn?”—and ends it with the same request for their WhatsApp number. The subscription packages for the three apps are neatly aligned, with the payment always directed to AIG’s partner company LinkYun Technologies. Tian didn’t respond to our question about the ownership of Pepper and Barfi.

On the Play Store, only Pepper noted AIG as its parent company. The rest keep their ownership information vague: L’amour is owned by “L’amour Team”; Barfi by “Barfi Team” and DPA by “Wiscom Corporation Limited,” a company which can’t be traced at all. However, the source code of Barfi mentions AIG as the owner.

Google search trends, a proxy for user interest, demonstrate the lifecycle of these predatory apps. Pepper’s popularity surged during the first half of 2019, only to fall—likely due to negative reviews—in August 2019, and that’s exactly when search for L’amour picked up.

There are many indicators that suggest L’amour will meet the same fate: from Jan. 11 to Jan. 14, the app slipped out of the list of top-10 grossing apps—it wasn’t even in the top 500 during that time—only to return to its number six position on Jan. 15.

L’amour may disappear again, but if it does it will likely reappear in a new incarnation. India’s dating-app scams are seemingly here to stay.

Snigdha Poonam is a Delhi-based journalist and the author of Dreamers: How Young Indians Are Changing the World.

Samarth Bansal is a freelance reporter based in New Delhi where he writes about technology, politics, and policy.