Data show India’s coronavirus lockdown may not be working

India is unique among the world’s major nations in having implemented a total lockdown for such a long duration in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

India is unique among the world’s major nations in having implemented a total lockdown for such a long duration in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic.

The move crippled about 75% of the economy, according to Japanese investment bank Nomura, which has also predicted an almost 4.5% drop in GDP due to this in financial year 2021. In the April-June quarter alone, the Indian economy would contract by 6.1%, the company has said.

Besides causing massive supply-chain disruptions, the lockdown has internally displaced millions of people.

Did it help?

Prime minister Narendra Modi’s government, which today (April 14) extended the lockdown till May 3, has argued that all this was necessary to “flatten the curve” of infections. However, the evidence it offers to back this claim is entirely unconvincing.

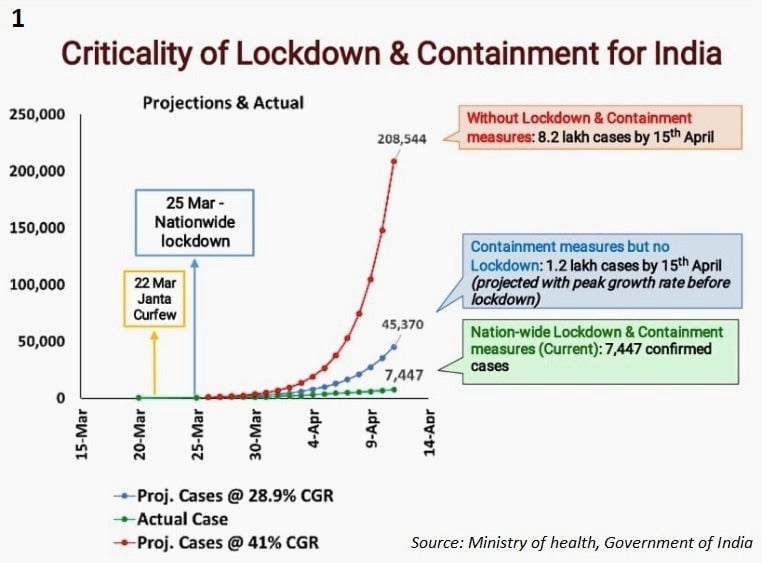

An external affairs ministry official, for instance, claimed on April 9 that in the absence of a lockdown, there would have been 820,000 cases by April 15, according to an internal assessment. When asked about it, the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) initially said no such study existed and later clarified that the claim was made based on a “statistical extrapolation” by the ministry of health as depicted in chart 1.

The problem with this claim is that we are not told what, if any, model was used to arrive at these numbers. No such model has been made public or even talked about by government officials. As it happens, the only model that ICMR has shared publicly is not about the lockdown, but an analysis of the border screening measures India introduced relatively earlier than other countries.

So what is the right way to know if the lockdown helped?

In the absence of an official reference model in India, all we have to go on is aggregate data on total confirmed cases nationwide, which is updated every day. The chart below plots the natural logarithm of total cases on the vertical axis with the time index on the horizontal.

The interpretation is that if the curve is flat there is no growth in infections and if the curve looks like a straight line, then infections are growing at a constant proportional rate. In other words, the classic exponential curve used in epidemiology.

It shows that after a basically flat portion with low growth in new cases, India entered the exponential phase, beginning March 4 or so, as captured by the straight line in the log of confirmed cases. Note that this exponential growth kicked in several weeks in advance of the lockdown and continued up to merely two days before the initial lockdown period was to end.

An optimist might perhaps see a minuscule flattening of the curve from around March 30, but this is only a week into the lockdown. Given that the virus has a two-week incubation period, it obviously cannot be attributed to the lockdown. What is more, several states had initiated their own lockdowns in advance of the national one. Karnataka, for instance, announced one on March 13, Maharashtra on March 20.

If the lockdown had any effect, you would expect the slope of this line to flatten or bend toward the horizontal axis.

Given the significant economic and human cost suffered due to it, the lockdown must, thus, be accounted for as a failure.

Lost opportunity

The bigger problem is that a focus on the lockdown takes away from the crucial question of ramping up testing.

There is no question that testing in India remains low by global standards. India has so far conducted over 200,000 tests as compared to a 100,000 per day in the US. The tourist hotspot of Goa, which hosts visitors from all over the world and, therefore, is a likely virus hotspot, has so far carried about only a little over 400 tests for a population of 1.5 million. Yet it remains under total lockdown, reporting only seven cases and zero deaths till now.

If, on one hand, we assume that India is testing enough and its numbers are accurate, we must ask if it makes any sense at all for a state like Goa to be under lockdown. By extension, is there any compelling rationale for a national lockdown which extends to many states that have had very low incidence of the virus? Clearly, one-size-fits-all isn’t the most sensible approach.

However, if we believe that infection rates are much higher than reported, it appears India missed a golden opportunity during the lockdown to build up its medical and public health capacity.

This is to say nothing of the economic and humanitarian disaster unleashed by the surprise lockdown. Rather than deploying the state’s limited capacity—low even during normal times—to set up hospitals and clinics, and ramping up testing, it has perforce been directed towards setting up relief camps for the poor and the destitute caught in the lockdown fiasco.

Any which way you look at it, the lockdown, without an attendant public health response, has failed to live up to its billing. And yet, here we are with the lockdown being extended.

We welcome your comments at [email protected].