Fake news about wild animals reclaiming urban spaces may seem cute, but it’s dangerous

Around a month ago, an Indian film star shared a video of dolphins near Mumbai shores, on social media.

Around a month ago, an Indian film star shared a video of dolphins near Mumbai shores, on social media.

She attributed their appearance to the fresh air following the shutdown that had begun in the city—a few days before the nationwide, government-mandated lockdown to prevent the spread of the coronavirus. The video, viewed over 118,000 times, was shared widely on social media with people celebrating the appearance of the dolphins, with some even terming it as a “rare” occurrence and the dolphins “coming back.”

But for those who study the city’s ecology, know that these dolphins are among Mumbai’s regular non-human residents. They’ve been documented around Mumbai’s shores for the last 15-20 years.

Shaunak Modi, co-founder of Coastal Conservation Foundation and member of Marine Life of Mumbai, who in fact photographed the same pod of dolphins a month before their video began to be widely circulated as linked to the lockdown, points out that this species, the Indian Ocean humpback dolphin, is a coastal cetacean species and lives in near-shore waters.

Its appearance is not rare and researchers as well as enthusiasts, some of whom can see these dolphins from their homes, have been documenting these marine creatures for years.

The misleading video of dolphins is one among many such visuals of animals in the city, that are being widely shared, as India stays at home in an ongoing lockdown that began in March. In the quest for a silver lining in this difficult time, the narrative of animals “reclaiming” human-dominated cities seems to have struck an emotional chord.

The accounts of sightings, some true but several misleading, have made their way through WhatsApp forwards to social media and even to some online and mainstream media outlets.

But are animals really “reclaiming” spaces as claimed? Turns out, in most cases, the animals have always been in these urban areas.

Additionally, many videos and photos of animal presence during lockdown have in fact turned out to be cases of misinformation and unrelated to the lockdown—the elephant strolling through Dehradun was an old video, deer on Ooty-Coimbatore road was a photo from Japan, whales at Bombay High was a video from Indonesia and most recently a picture of peacocks and other birds being circulated with claims from various locations was found to be an old photo.

Even internationally, many widely shared pieces of information about animals moving around during the lockdown, with the one about dolphins in Venice canals being the earliest one, have been debunked.

Always there, only more visible now

Multiple experts validate that many of the animals and birds that are coming into the spotlight during the lockdown are in fact of those that have always lived in close proximity to urban spaces.

They are not “returning” to these spaces because of the lockdown, as some claim. They are only being more noticed now, perhaps because of the absence of humans and traffic and also perhaps that people have more time, too, to make these observations.

What could also be true, though, is that with the absence of traffic and human threats to urban-dwelling animals, they are more bold and willing to explore, for example, taking the chance to cross roads which they wouldn’t have ventured out into earlier.

The leopards residing in Aarey Milk Colony in the midst of Mumbai are one such example—they’ve always been living there but without traffic and human interventions, they’ve had a chance to roam a bit more freely, as indicated in camera traps.

“Even without going into whether these videos are fake or not, I am not surprised with any of the videos—they are all animals we regularly see in cities. We have sambar in Chandigarh, we have nilgai in Delhi, we have elephants in Haridwar, we have the small Indian civet in Kerala—they are already there and in significant numbers,” explained a forest officer who preferred not to be named.

“Cities in India have rich biodiversity—birds, for example. It’s not that these birds have suddenly come to Delhi. Delhi, in fact, has the second-highest bird diversity than any capital in the world, before the lockdown as well.”

A more likely theory is that birds are now simply spreading their wings further and even breeding in previously human-occupied areas, say some experts, combined with the fact that birds are also being documented more by citizens under lockdown.

Modi, who has been tracking some of the misinformation around Mumbai’s marine species, said, “This is not nature reclaiming, nature’s always been there. We are lucky enough to live in a city (Mumbai) which has a big cat population, as well as dolphins and a lot more.”

Among the misleading videos of animals in and around Mumbai was also one of whales, claimed to be in the waters around Bombay High, an oil rig near Mumbai shores. It turned out to be an old video from Indonesia being passed around with misleading text.

“As far as whales go, they have been seen in certain areas of Maharashtra and there was even a video shared by a fisher of a sighting in deeper offshore waters off Mumbai.” explains Modi. Dolphins though are better documented in Mumbai waters for years. Other than in the waters off the south Mumbai coast, there are dolphins spotted at Haji Ali, Worli, Juhu, and even Madh Island.

Other animal appearances, that are usually a regular occurrence but are now being falsely linked to the lockdown, include peacocks in Mumbai around the Hanging Garden area, rosy starlings murmuring at the Sabarmati riverfront in Ahmedabad, Gangetic dolphins in Kolkata after three decades and olive ridley turtles mass nesting in Odisha.

The repeated instances of misinformation about animals not only give false hope and pollute the information environment but also undermine the fact that many of these animals have been coexisting with humans for years.

The epidemic of misinformation

Misinformation, colloquially called “fake news”, is false information shared inadvertently and could range from manipulated content to content shared in a false context and more. The United Nations secretary-general Antonio Guterres warned in a statement on April 14 that the world is facing “a dangerous epidemic of misinformation” about Covid-19 and announced a UN campaign with a common cause for common sense and facts.

In the flood of false news during the Covid-19 pandemic, the misinformation featuring animals is not as widespread as myths about the origins and spread of the coronavirus or hoaxes implicating governments.

Karen Rebelo, deputy editor at the Indian factchecking website Boom Live, where they get anything between 50 to 100 queries on fake news every day, underlines that the false news around animals and the environment is a very niche category of misinformation seen during this period and is certainly not a trend so far.

“These stories are not conjured out of thin air. We have seen evidence of the natural environment improving because of the lockdown. So these stories have some grain of truth to it. Though a lot of times people get carried away or share a video in order to go viral or sometimes even as a joke,” she said.

An analysis by Poynter Institute-led Corona Virus Facts Alliance, of over 3,500 fact-checks by 100 organisations globally, found that the animal-related misinformation has been steadily ongoing right from early January.

Fact checkers have been debunking several of these hoaxes and according to the analysis, the number of fact-checks specifically on the topic “animals,” is the highest (40 so far) in India.

“It’s harmless…what’s the problem?”

The “over-abundance of information, some accurate and some not, makes it hard for people to find trustworthy sources and reliable guidance when they need it,” said the World Health Organization, when it announced in a situation report in February that the novel coronavirus outbreak and response has been “accompanied by a massive ‘infodemic’.”

While the sharing of misinformation around animals does not usually pose an immediate danger, it does add to the noise that blocks access to genuine information.

The seemingly harmless misinformation could also have impacts in the long term on mindsets and attitudes of people consuming information. “It is important that people are in a mindset of not easily accepting things they see online,” said Eoghan Sweeney, a digital media consultant and open-source investigation trainer.

“And I know if you point out misinformation, people may come back and say “oh what harm is it, it makes people feel happy.” But I think this is something that goes right to the heart of attitudes. It shows that accuracy, truth, objectivity are not necessarily as crucial as they should be. So if you get people in a mindset where they will happily start sharing stuff without verifying, where do you draw the line? That can be quite dangerous,” he said, adding that it’s important to get people in a mindset to consume information critically and not get manipulated.

Misinformation is increasing chatter and it becomes difficult for those who are not experts, to sift out the genuine information, adds Modi, noting that people may not always understand the repercussions of sharing false information and maybe doing it more out of curiosity and fascination rather than ill-intent.

Sweeney, however, notes that there are cases where there is, in fact, malicious intent behind sharing false content. Most of these are to draw people into certain social media pages or individual accounts. These start off by posting seemingly harmless and attractive posts, get engagement and followers and then repurpose the page to do something more harmful or something that helps them make money.

“The expression I think is “like-farming” where you use this kind of information to draw attention. You then suddenly have an account with million or two million followers and then you can entirely repurpose the account and use it to feed harmful misinformation or disinformation,” he said.

“Animals, of course, elicit very powerful, visceral emotional responses in people. So if you’re looking for easy hits, animals will do the job,” he explained.

In a more direct impact, the spread of such misinformation could impact the work of people directly involved in handling of wild animals. In Chandigarh for example, an old video claiming to be that of an elephant roaming in Kaimbwala, Chandigarh, an unlikely occurrence since elephants are not found in Chandigarh, made officials do “futile activity”, claimed DCF Chandigarh Abdul Qayam on Twitter where he urged the public not to share fake news.

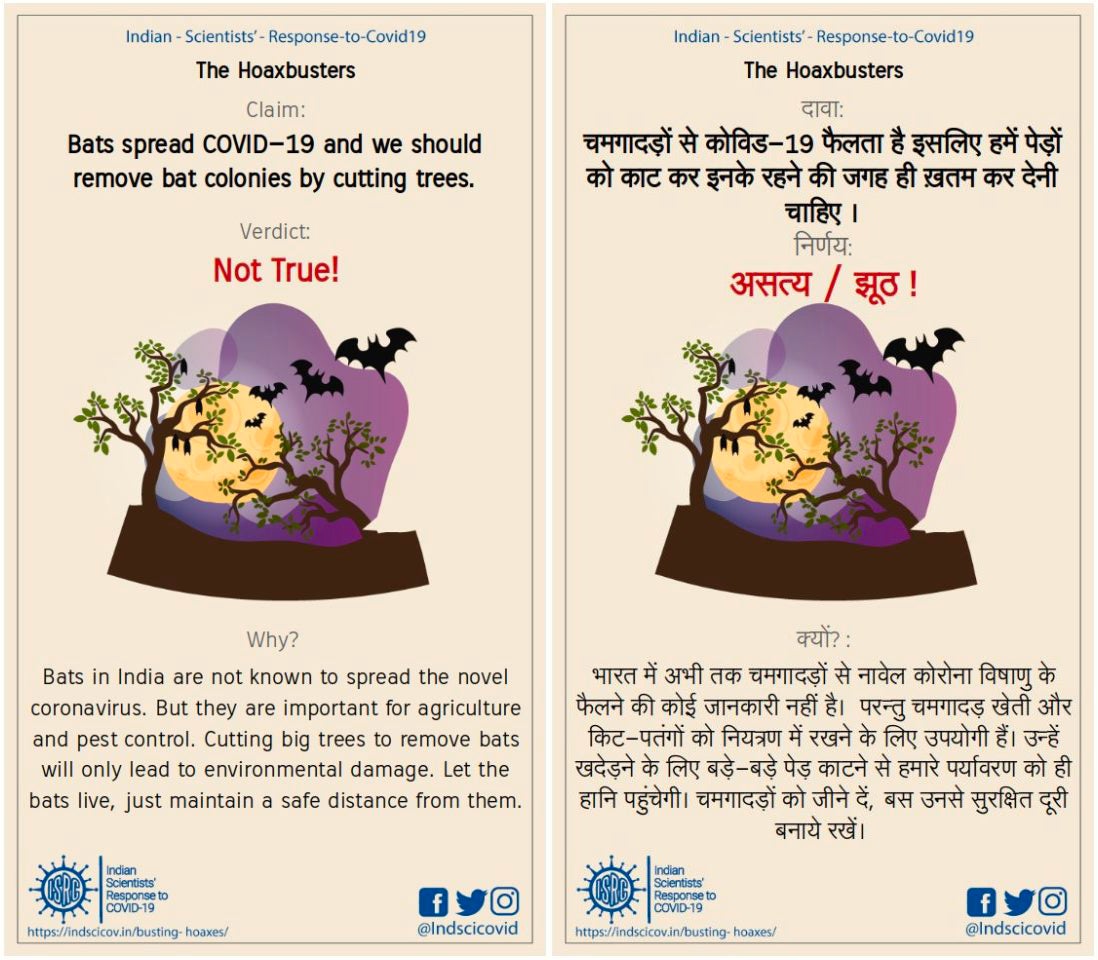

Further, misleading posts that elicit hatred and fear of animals, arising from ill-informed or oversimplified linkage of animals to the virus, have already seen negative impacts, like people demanding authorities to cut trees where bats live and abandoning pet animals on the streets.

Rebelo has hope though saying it’s not just all negative. In her experience, “people are realising the value of credible information. Fact-checking websites are gaining a lot of traction. In a lot of cases, they are going back to traditional (news) media and even willing to subscribe and support news outlets.”

Fighting misinformation with science

The Corona Virus Facts Alliance analysis shows that when the new coronavirus pandemic started, many hoaxes were about the origin of the virus, followed by how the disease spreads, and cures and preventions.

While the hoaxes are now shifting to being about religious groups, politicians and the impact of Covid-19 on a country’s health system, there is still a significant amount of misinformation around the science of the coronavirus.

What makes someone share misinformation though? The reasons are not necessarily negative and could sometimes come from a good place. “As human beings in modern times we are social creatures, we want to protect ourselves we also want to protect those in our immediate group,” said Sweeney, explaining how the protective instinct makes people share information they believe will protect their loved ones.

“Then there are our egotistical concerns—to think that you are in the know, that you are privy to content and knowledge that other people may not be—this really feeds into this spreading of conspiracy theories,” he said.

Added Rebelo, “You cannot expect people to behave rationally and keep their emotions aside when assessing information especially when they’re survival is under threat.”

The growing misinformation has given rise to Indian scientists coming out in the public sphere to fight fake news with authentic scientific information communicated in simpler terms.

Ramanujam R, one of the initiators of the Indian Scientists Response to Covid-19 (ISRC) collective that was formed during the lockdown to combat misinformation with scientific information, stresses that it is important for people to rely on science-based information “because it is a lifeline to save humanity—not merely in response to the virus, but quite literally to save the Earth,” he said. “Society is run by politics and economics which selectively use science for their purposes, and unless our understanding of nature and society is strongly rooted in science we have many barriers to overcome.”

Similarly, the multi-institutional science communication initiative, CovidGyan too aims to communicate scientifically credible and authentic Covid-19 related content and resources.

Meanwhile, the Wildlife Institute of India has observed the sharing of videos and photos of animals that people are apparently spotting during the lockdown and has developed an Android app, Lockdown Wildlife Tracker, to make the recordings more streamlined.

“In the time of the Covid-19 lockdown, where we humans are locked inside our homes, there are more and more reports of wildlife exploring human-dominated areas or ‘rewilding’ urban areas. However, these records are stray and just circulated as WhatsApp stories for now. This information is very critical in understanding human-wildlife interface in the country,” WII noted on its website.

“These sightings can be reported real-time as well as at any later period—but only till the lockdown lasts,” explained Bilal Habib, Head/Scientist E, Department of Animal Ecology and Conservation Biology in an email. As of mid-April, the app had around 250 users and 30 entries but it is too early to analyse this information.

The efforts to counter misinformation with science and facts are on a global scale with even the UN. announcing a new initiative with this aim. “Together let’s reject the lies and nonsense out there,” said the UN secretary-general in a video message.

The impact of misinformation

While misinformation on science and environment rears its ugly head in various ways and government and scientists are having to dedicate time and resources to debunking it, the impacts on research and conservation are yet unclear.

In fact, more than social-media-based information, it is long term environmental policy and people’s push for it that will make a real difference to wildlife, stressed the forest officer.

Modi said, “I think the impact on research remains to be seen. Initially, I see it as a positive, how many ever people find out about it (animals) it’s good. On the other hand, it also undermines the work of a lot of people.” He gives the example of Mumbai, where environmentalists have been opposing the coastal road for its impact on marine life, much of which has been documented by Modi and various other marine life researchers and enthusiasts.

“When someone flippantly says this (appearance of animals) is attributed to the lockdown or that it is rare and they are not here usually, all the work we are doing (in researching and documenting marine life) gets washed away.”

While certain changes to the environment are truly noticeable with the lockdown—lower aerosol levels, better air quality and bird activity—experts hope that these will inspire people to maintain their concern towards the environment even after the lockdown.

Ecologist and sustainability educator Harini Nagendra hopes that the lockdown and people’s observances of the environment will encourage more citizens to give a ground push for better environmental policy. “If this period can make us realise we have a right to bird song, clean air, landscape views, we can push government for better policy for a better life,” she said.

This post first appeared on Mongabay-India. We welcome your comments at [email protected].