Why Uber transit won’t work in India

Nearly a year after launching its public transport feature in Delhi, Uber is all set to ride into its second Indian city.

Nearly a year after launching its public transport feature in Delhi, Uber is all set to ride into its second Indian city.

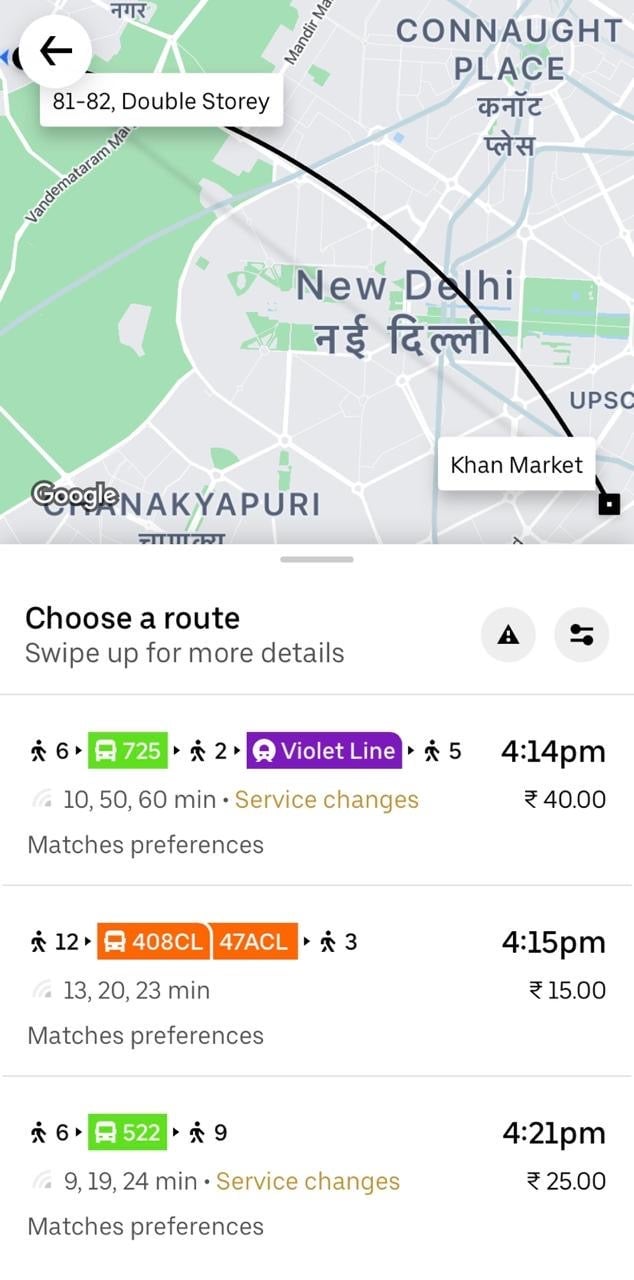

The feature provides commuters with information about nearby public transit stops and real-time departure schedules.

On Sept. 17, Uber said it has partnered with Hyderabad Metro Rail (HMRL), Larsen &Toubro Metro, and the Telangana State Road Transport Corporations’ (TSRTC) bus service in the southern Indian city of Hyderabad to help riders plan their transit journey end-to-end within its app.

The feature can help in improving urban planning as it allows governments to better manage their resources and match supply with demand. “The platforms provide a data-driven approach to knowing peak demand times and areas. This can help cities and governments better allocate public transportation to reduce crowding and serve the needs of residents,” Rajkumar Venkatesan, professor of business administration at Darden School of Business at University of Virginia, told Quartz.

While great on paper, India’s roads may not be ready for it. For one, the overcrowded buses and trains are always filled to the brim. Secondly, punctuality is a weak point. Over 30% of Indian Railways’ trains ran late in 2017-18.

“To be useful, the app will need to reflect different conditions, availability of different transport modes, highly variable service quality (e.g., not running on schedule), and highly variable infrastructure in different cities and towns of India,” said Anjali Mahendra, director of research at World Resources Institute’s Ross Center for Sustainable Cities. “The app will only be as useful as the reliability of the information in it. If people find they can’t trust it after a couple of trips, they will not use it.”

Riding into India’s public transit

Uber Transit Journey Planning is currently available in more than 15 cities across the world, including Massachusetts in the US, London in the UK, and Nice in France.

“Our goal has always been to complement public transport and by providing riders with more choice, and more ways to connect the first and last mile of their commute, we hope to encourage greater use of public transportation,” an Uber spokesperson said.

But what’s in it for Uber?

The big push by the aggregator is to bring in more users from the middle and lower-middle classes, who use public transport for the longest trip they make in a day, as per WRI’s Mahendra. Less price-sensitive users may compare commute times between a cab and train with just the cab, and take the latter. Some may only travel the distance to the station. “Either way, these companies gain,” she said.

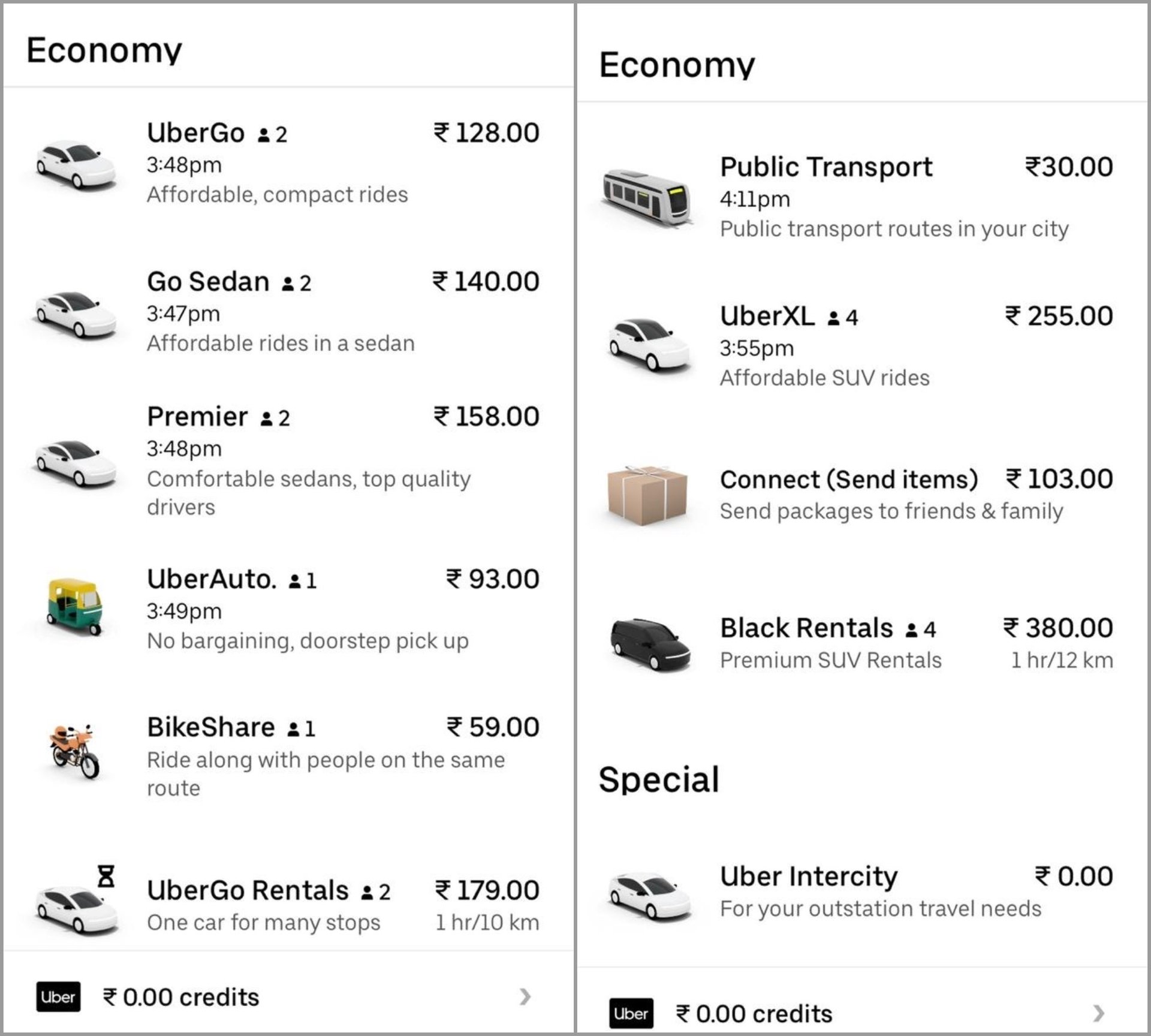

And of course, Uber can give itself priority. For instance, when you map an 8 km route from New Rajinder Nagar to Khan Market in Delhi, the Uber app shows you three cab options, UberAuto, it’s bike-share service, and short-term rental options, before showing the cheapest public transport option.

Besides, mapping is one of the biggest challenges and among the costliest undertakings of a project like this but cab services are already working on it for their core offering. Plus, they’ve already figured out payments, making ticketing a possibility, too. In fact, Uber Transit Ticketing has already been rolled out in 13 American cities.

In the long-run, it paves the way for the cab-aggregators to provide integrated fare services across public transport modes to all users, making themselves the go-to app for travel solutions that may even replace Google Maps, according to Rahul Kashyap, chief operating officer at public relations firm PRP group. No wonder Uber isn’t alone in eyeing this space.

Back in 2018, Uber’s Indian rival Ola had acquired transportation information provider Ridlr to expand its public transit business.

“The bigger play here is that the technology becomes something public transport authorities use to operate manage their services,” said Madhav Pai, who leads the World Resources Institute’s Cities & Transport programme in India. This is apparent from Uber’s moves in the west: In June, it made its first software deal with Transportation Authority of Marin (TAM) and the bus agency Marin Transit. A month later, it acquired Atlanta-based Routematch to offer more services to cities.

The Covid-19 pandemic may have come as another advantage. “People are now worried about crowded spaces, they want real-time information on their buses and their level of crowdedness as well to make a choice to use public transport,” said Ravi Gadepalli, a Bengaluru-based independent consultant for transit policy, planning, and operations.

Beyond convenience, pushing public transport is also crucial for environmental reasons—a necessary move at a time when Indians have begun prioritising car ownership.

“The cities are becoming more and more congested every day due to higher vehicle usage. This is leading to severe pollution, accidents, incidences of road rage, and time loss,” said Vaishali Singh, senior associate, urban planning and design at Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP). “Cab-aggregators have the capability and good technology to understand people’s travel behaviour. In the coming days, they can help public transport agencies with their route planning.”

But the India plans are chugging along too slowly to make a big impact.

A bumpy road for Uber in India

For now, the India experiments are just pilots, experts stress.

Hyderabad is not a daring pick considering Uber already has a relationship with the region. In 2015, it signed a deal with the Telangana government, committing $50 million in investments. The company also has an office there, where its global fintech team operates from.

Whether or not it enters other Indian cities will be the real litmus test.

In parts of the US, the state pays Uber subsidies to run its service near transit stations. But in India, any concession is probably out of the question given that Mumbai and Delhi bus services are struggling with mounting debt, and strained under Covid-19, Indian Railways is staring at a colossal Rs35,000 crore ($4.8 billion) loss this year.

Additionally, the next steps are unclear. Elsewhere, Uber is cracking deals to run routes instead of the state but in India, current regulations won’t allow public transport permits to private players, explained Gadepalli. Governments may also worry the likes of Uber may use their data to cut into their demand. Studies have shown ride-hailing services have a more substitutive effect on public transport than a complimentary one.

What’s more, is that public transport in India is battling a massive safety crisis. A dismal 9% of urban Indian women feel safe in public transport.

“If cities are serious about this, they need to make sure the right infrastructure is also available to make the experience seamless,” said WRI’s Mahendra. Some examples included creating dedicated, safe places for Uber and Ola drop off and pick up points at stations; ensuring regulation over prices, safety, and quality of service; and demanding that these companies share user trip data.