Why are India’s farmers and politicians opposing the new agriculture reforms?

India’s parliament was operational on a Sunday for the first time ever, because the pandemic delayed and shortened the monsoon session. But it was a day for another first.

India’s parliament was operational on a Sunday for the first time ever, because the pandemic delayed and shortened the monsoon session. But it was a day for another first.

The upper house of Indian parliament yesterday (Sept. 20) passed two agricultural reform bills by a voice vote. This meant the deputy chairman of Rajya Sabha (the upper house), Harivansh Singh, proposed the bill, and members were to respond verbally with “ayes” or “noes.” The deputy chairman then made a decision based on his perception of which side is louder.

Typically, votes happen digitally, with a scoreboard displaying the tally.

This, members of opposition political parties say, is “murder of democracy.” After they were prevented from speaking in parliament, opposition party politicians climbed atop tables, attempted to tear the rule book, and tried to snatch away the deputy chairman’s mic. Eight such MPs have been suspended today (Sept. 21).

The contentious farm sector bills, meant to liberalise the industry by opening it up to private players and companies, were opposed by several parliamentarians from Congress, Aam Aadmi Party, Trinamool Congress, and DMK. They allege that they were not allowed to speak, their mics muted, and the house was packed with security personnel to prevent any dissent.

Reports also suggest that the audio of the government broadcaster Rajya Sabha TV was cut off during this voice vote.

Beyond the contentious circumstances under which this voice vote took place, the farm sector legislation has led to farmers, especially in the northern states of Haryana and Punjab, coming out into the streets.

Why are farmers protesting

The new legislation seeks to allow private market forces into the largely government-regulated farm sector in India. Currently, farmers take their produce to wholesale markets or mandis governed by the Agricultural Produce Market Committee (APMC). The APMC in every state decides the prices it will pay the producers, and then sells them further.

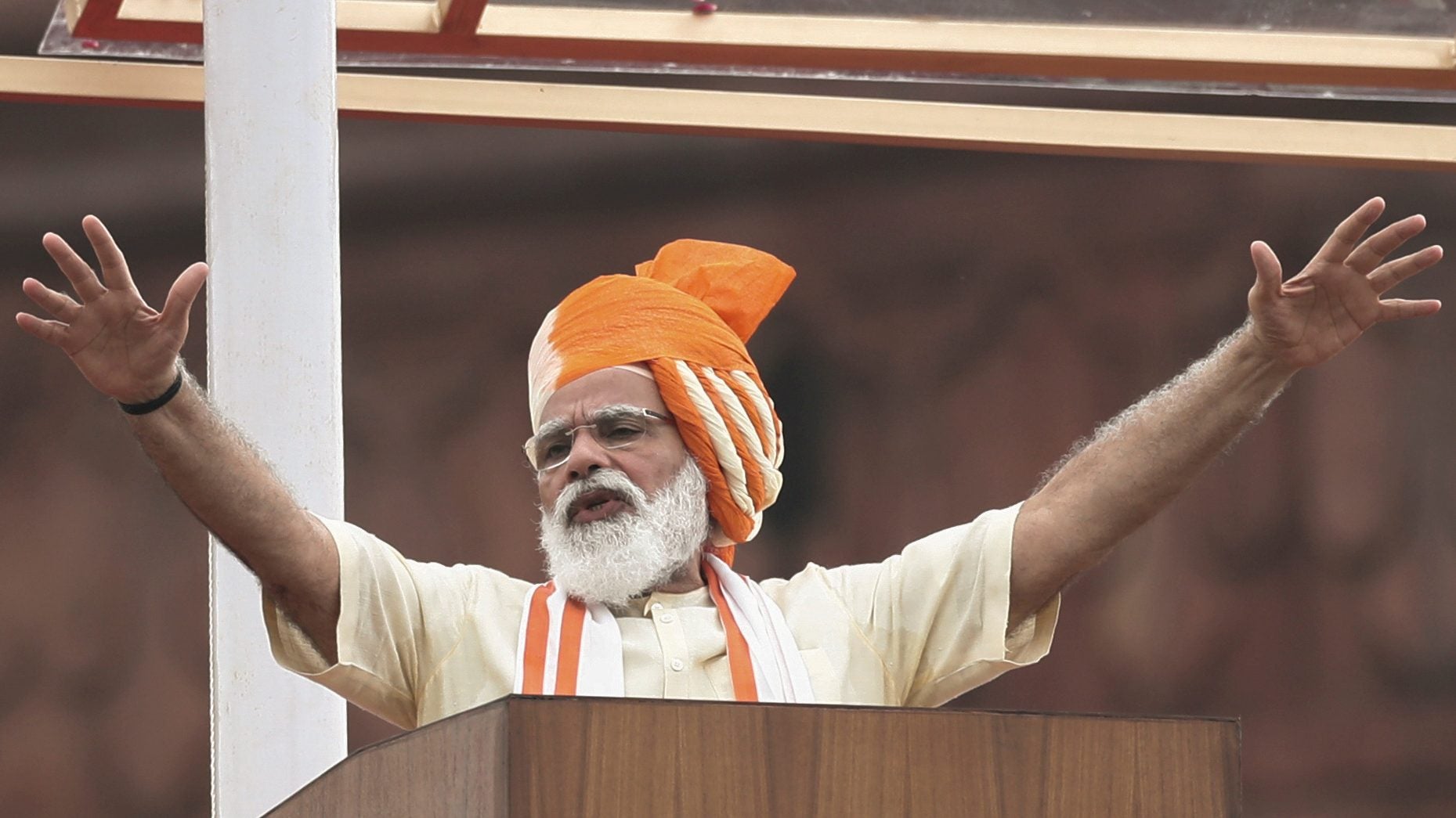

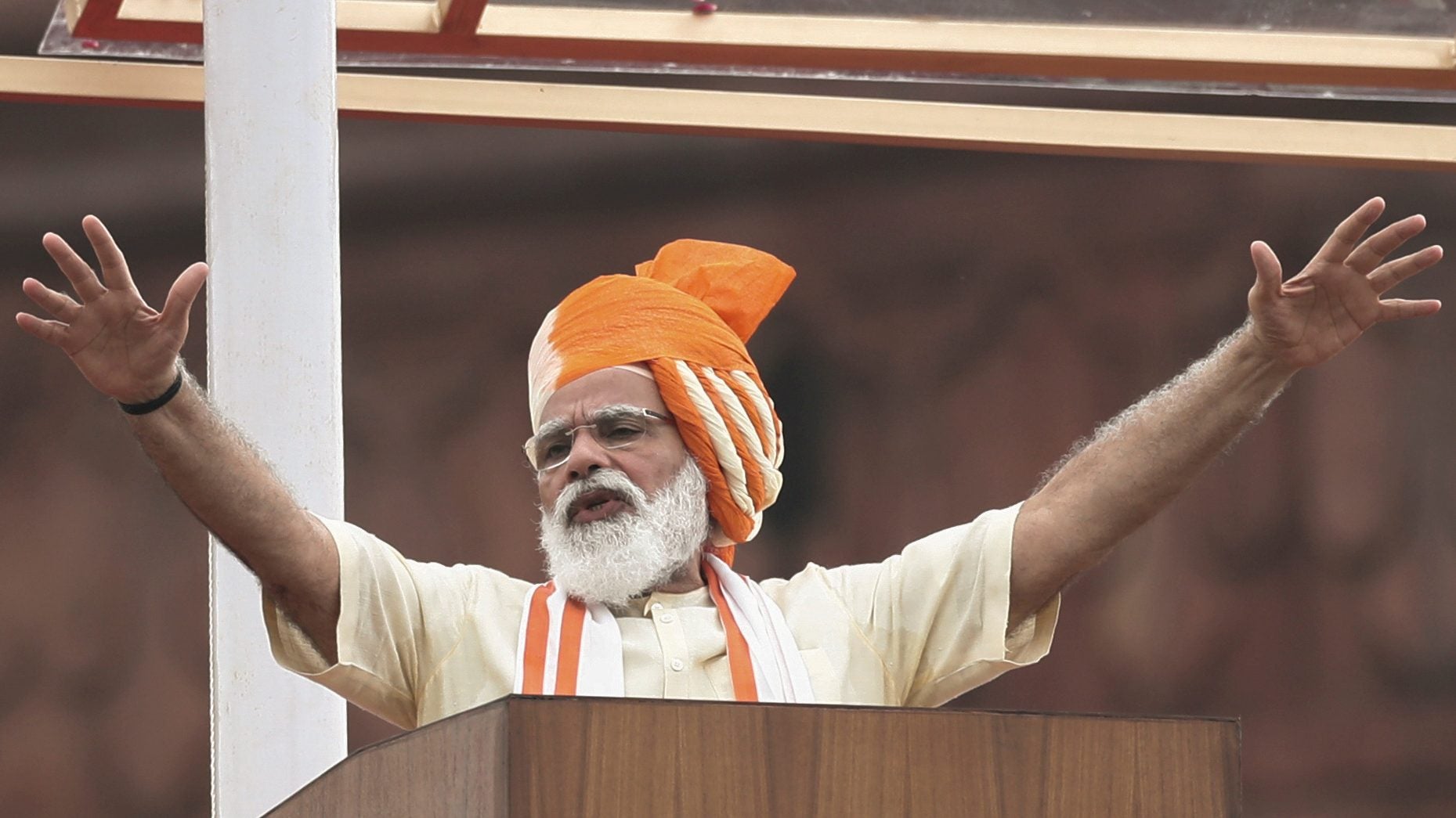

Historically, this has meant that farmers have a market certainty for being able to sell their produce. The Narendra Modi-led government has argued that by allowing private players, the farmers can potentially negotiate higher rates and become active participants in their economic prosperity.

The fear surrounding the new legislation also stems from the long-standing convention of minimum support price (MSP), which the government offers as a cushion to farmers against a sharp price fall during a particular season. Farmers and opposition parties are apprehensive that the MSP would lose its teeth with a pure market play.

But the laws themselves are not shutting down the APMC mandis or the practice of MSPs. These would, on paper, offer a greater degree of autonomy to producers.

The MSP convention isn’t foolproof, either. According to the 2015-16 agriculture census, 85% of the farm holding in India falls in the small category at less than 2 hectares. As such, the small farms have suffered because of the MSP system, because the farmers are net buyers of food produce, The Indian Express newspaper wrote on Sept. 20.

This, then, points to a certain trust deficit against the central government. Modi’s government, for instance, changed export rules on onion 17 times between 2014 and 2019, hurting the economic interests of the farmers. Export rules for rice were changed 14 times during the five years ending 2019. Recently, on Sept. 15, it stopped the export of onions again to prevent domestic market prices from going up. The ban was eventually reversed on Sept. 18.

The scepticism against these bills also emerges out of the lack of information available to farmers to negotiate the right prices for their produce in the open market.

Protests and confusion around the farm bills led defence minister Rajnath Singh to address the agriculture bills during a press conference yesterday.