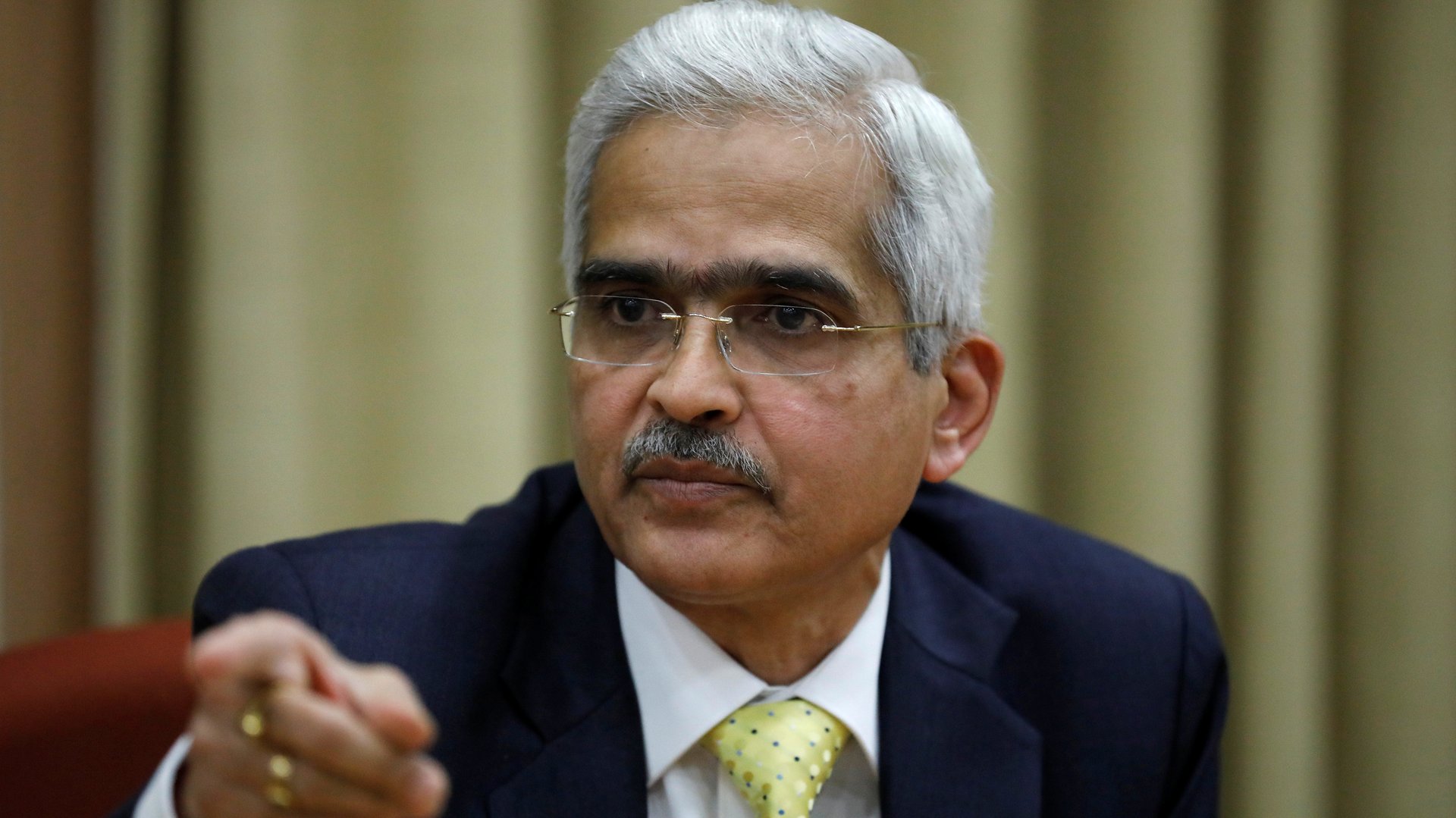

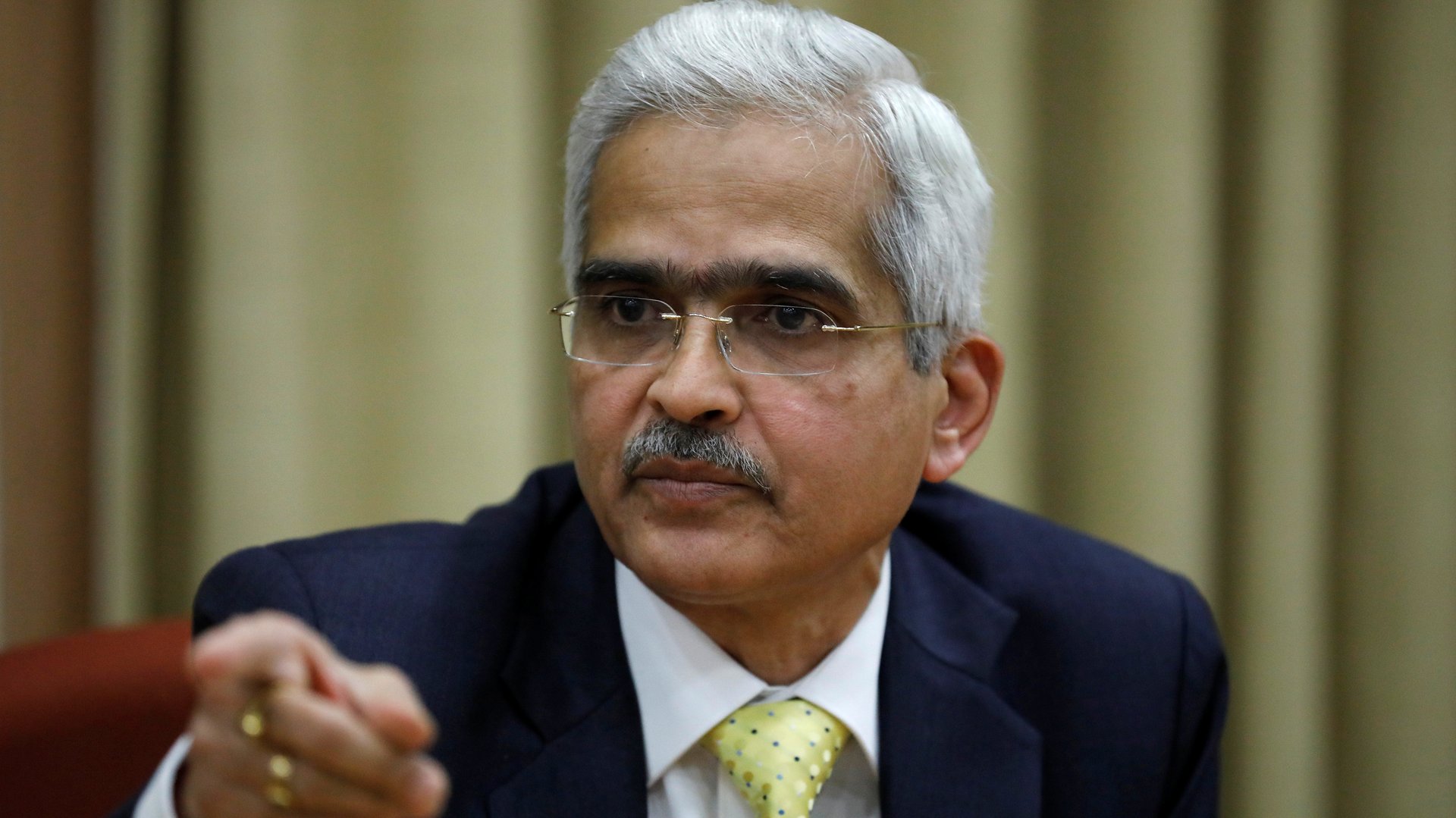

What has Modi’s handpicked central bank chief accomplished two years in?

In December 2018, the Narendra Modi government put an end to a bruising battle with India’s central bank by appointing a former bureaucrat Shaktikanta Das as the Reserve Bank of India governor. The appointment followed months of public spatting between Das’s predecessor Urijit Patel and the government over the autonomy of the central bank. This rift had spooked stock markets at a time when the Indian economy was on weak ground.

In December 2018, the Narendra Modi government put an end to a bruising battle with India’s central bank by appointing a former bureaucrat Shaktikanta Das as the Reserve Bank of India governor. The appointment followed months of public spatting between Das’s predecessor Urijit Patel and the government over the autonomy of the central bank. This rift had spooked stock markets at a time when the Indian economy was on weak ground.

So, from his first day, on Dec.12, 2018, Das inherited political friction, besides the Herculean challenge of dealing with a slowing economy.

Two years on, he may have managed to ease concerns on one front very effectively, but on the other, things have only become worse.

Saving the Indian economy

RBI’s relationship with the government eased almost overnight after Das’s appointment. After all, he had worked at the finance ministry for three decades, navigating varying political hues. He was also Modi’s lieutenant during demonetisation, and there was a wide belief that he had been hand-picked to ensure there was a smooth relationship between the government and the central bank.

To his credit, the history major also started ringing in some bold economic changes soon after taking over.

For instance, in order to boost economic growth, Das started cutting interest rates within months of his appointment, a sharp departure from RBI’s earlier policy stance, where in October 2018, Patel had declared that rate cuts were “off the table.”

Das also doled out higher dividends to the government from the RBI’s coffers and instructed banks to restructure stressed loans of medium-, small- and micro-enterprises (MSMEs), which are seen as the backbone of the Indian economy.

The hope was that more money in the hands of companies and people would result in more spending and give the economy a push. But that’s not how things really panned out.

Banks, reeling under a mounting bad loan problem and weak economic environment, were conservative in doling out more loans.

Despite lower repo rates (the rate at which RBI lends to banks), credit growth during 2019 declined.

And then, almost overnight, things got a lot harder for Das.

Coronavirus’ wrath

In March, when India went under severe government-mandated lockdowns to arrest the spread of coronavirus, the economy came to a near standstill. For instance, in the month of April, there was not a single car sold across the country. To brace for future uncertainties, many companies started cutting costs by laying off staff or reducing salaries.

In the first and second quarters of the financial year, the Indian economy contracted by 23.9% and 7.5%, respectively.

Das has tried to rise to the challenge. Between March and December, the RBI cut repo rates by 115 basis points, hitting a record low of 4%. In February and March, the RBI also offered money to banks at a cheaper rate. Yet again, the hope was that this would encourage companies to borrow more from banks and plow the funds into boosting growth.

Experts complimented Das over this move. “The RBI read the slowing growth much ahead of the market back in February 2019 and acted proactively by cutting rates and adding liquidity,” said Pankaj Pathak, fund manager for fixed income at Quantum Mutual Funds.

But, data shows, that Das’s plan didn’t work.

“The markets are flush with liquidity, yet private borrowing has been low. For the private sector, particularly MSMEs, it is more an existential question,” said Partha Chatterjee, dean of international partnerships and head of the department of economics at Shiv Nadar University.

It’s not just banks, but even bond markets are reluctant. In October, for instance, Das entered into a direct conflict with bond markets, as they were demanding higher yields. “Market participants need to take a broader time perspective, bid with sensitivity to signals from RBI,” said Das. But his warning fell on deaf ears.

The central bank rejected all the bids by bond traders for 10-year government bonds. “The market wanted a higher interest rate than what RBI was willing to concede. This increased the 10-year-bond rate by 5bps to 6.04% in September,” observes Chatterjee.

Economists have estimated that in the financial year ending March 2021, the Indian economy may contract around 10.3%. And even if this poor show can be blamed on coronavirus—that’s dented some of the world’s strongest economies—there’s another parameter on which Das and his team hasn’t been able to deliver.

RBI’s battle with inflation

Inflation has been a bone of contention in India’s policymaking for years. Under Das’s leadership, the central bank has increased focus on growth even as inflation has continued to rise.

The RBI monetary policy committee that takes the call about rate cuts has claimed that inflation will eventually start subsiding because it is mainly due to supply-side problems and high vegetable prices.

Now, with the Covid-19 pandemic rummaging the economy, experts believe the central bank is not in a position to give up on its aggressive focus on growth.

“Any attempt to control inflation… would come at a huge growth sacrifice. Given the current state of the economy, I think the RBI has been pragmatic in the way in which it has used monetary policy,” said Tulsi Jayakumar, professor of economics and chairperson of Family Managed Business at Bhavan’s S.P. Jain Institute of Management and Research.