India’s incomplete Covid-19 data doesn’t begin to capture the crisis in Delhi

In India’s capital city hospital beds are a prized commodity right now.

In India’s capital city hospital beds are a prized commodity right now.

With the city clocking over 20,000 new Covid-19 cases for over 10 consecutive days, there is an acute shortage of healthcare infrastructure. Besides the widely-criticised shortage of medicines and oxygen supply at hospitals, Delhi, a city of 16 million people, has nearly no space left to even accommodate patients anymore.

As per chief minister Arvind Kejriwal, the positivity rate in Delhi has reached 30%, and as of April 18, there were only 100 ICU beds left unoccupied.

The state’s government has been trying to ramp up capacities but has failed to keep pace with the spread of the disease. Kejriwal has promised that 1,200 more ICU beds will be set up in Delhi by next week, and another 500 will be added by next month at a temporary set-up at Ramlila Maidan, a large ground that is traditionally used for religious festivals.

But for now, finding a hospital bed is a daily fight for thousands of Delhi residents.

Total Covid-19 hospital beds in Delhi, and the portion occupied

Inaccurate beds data

Even as Delhi is among the very few states in India that are consistently publishing data on the availability of beds, the figures do not match with the stories of those struggling at hospital gates in the city.

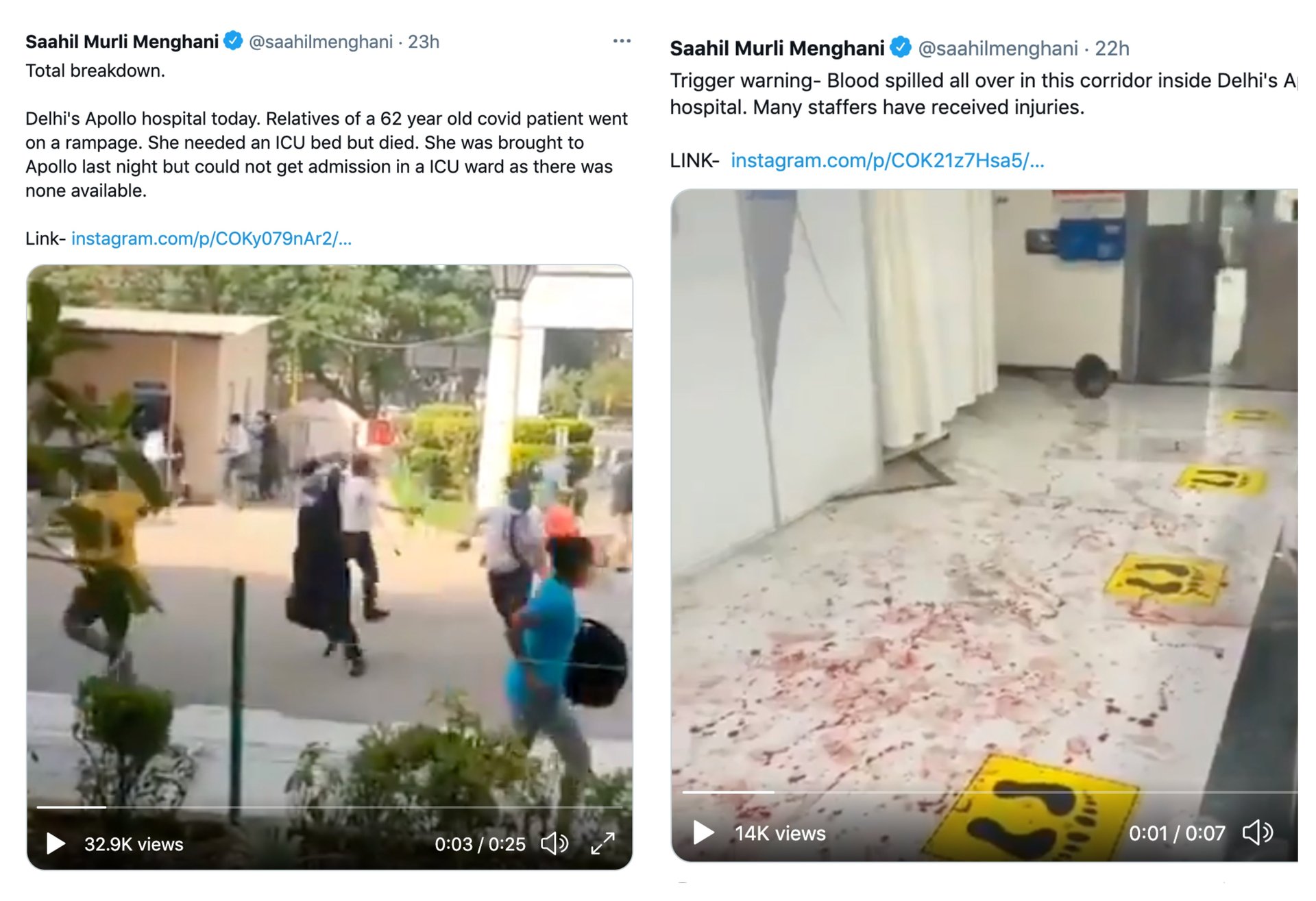

Social media in the country is flooded with stories of Delhi residents running from pillar to post trying to secure beds for severely ill Covid-19 patients. Many of them act on the basis of the official government data but are turned down at the hospital gates.

Several such unfortunate patients are lying outside hospitals unattended, while many others are dying before they get admission at any hospital.

A possible reason for the discrepancy in data is that many hospitals are not updating the bed availability status at their facilities in real-time on the Delhi Corona app, which is supposed to help patients find hospitals, ventilators, and ICUs.

On April 18, the Delhi government filed first information reports (FIRs) against hospitals that showed inaccurate information. Ten days later, though, the problems still persist. And if battling a system laden with inaccuracies wasn’t rough enough, many beds that are vacant are not available for the common person.

VIP culture at Indian hospitals

Delhi, the capital city of India, is home to the country’s government and bureaucracy, besides many other influential government officials. The city’s famed power politics has made it hard for even “insiders” to access medical help.

For instance, on April 25, a resident doctor at All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), one of India’s most prestigious hospitals, was not able to secure a bed for his sick father because rooms at the south Delhi facility were reserved for politicians.

Over the last two weeks, at least 150 nurses and more than 200 doctors at another major government hospital, Ram Manohar Lohia (RML), have tested positive. But RML turned its back on seriously ill staff despite having 35 vacant “VIP” nursing home rooms. “A staff member of a politician will get a bed even if there are other patients who require urgent oxygen facilities,” explained a health worker.