India’s $1.6 billion fund to clear the world’s most toxic air has been a non-starter

The cassia tree blooms in October, with an explosion of small yellow flowers over a canopy of light green. But you wouldn’t notice its extravagant beauty on the road between Anpara and Shakti Nagar, in Uttar Pradesh’s Sonbhadra district.

The cassia tree blooms in October, with an explosion of small yellow flowers over a canopy of light green. But you wouldn’t notice its extravagant beauty on the road between Anpara and Shakti Nagar, in Uttar Pradesh’s Sonbhadra district.

On this 20-km stretch, the yellow and green of these trees are covered with a foggy grey monochrome. Touch a leaf, and your fingers return with a film of fine black coal fly-ash. Take a deep breath, and instead of the sweet scent of the flowers, your lungs fill with sulphuric fumes.

Yet, Sonbhadra rarely features in the discussion of India’s toxic air crisis. In popular perception, the crisis is limited to the winter smog over the national capital, New Delhi, and is caused solely by errant farmers burning crop stubble in Punjab and Haryana.

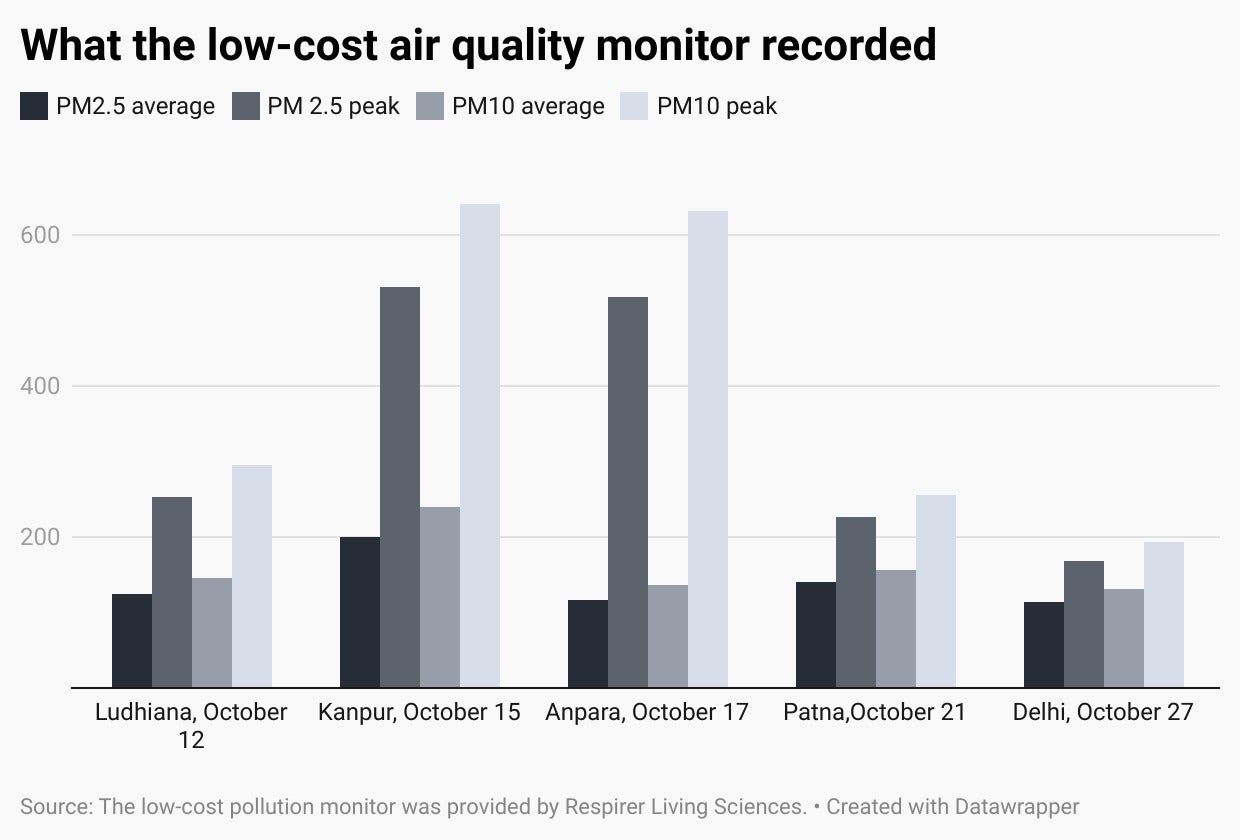

Nothing could be further from the truth. Travelling 2,000 km in mid-October from Punjab to Bihar, with a low-cost air quality monitor, well before winter had set in, I found consistently high readings of air pollution across the Indo-Gangetic plains.

Among the highest levels were recorded in Sonbhadra, in the southeasternmost corner of Uttar Pradesh, around 1,000 km from Delhi. According to the World Health Organization’s 2021 air quality guidelines, human health is at risk if levels of PM2.5, or particulate matter 2.5 microns or less in diameter, exceed 15 per cubic metre. These particles can enter the lungs and cause diseases like asthma, bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Similarly, the guidelines state that PM10 levels above 45 pose health risks.

In Sonbhadra, readings frequently spiked to over 500 per cubic metre for PM 2.5—33 times the safe levels—and over 600 for PM10—13 times the safe levels.

It is unsurprising that the air in Sonbhadra is so polluted. The first power plant of the National Thermal Power Corporation was set up in the district, and today the district is home to six coal mines and 12 captive and non-captive thermal power plants.

To build this energy capital, as Sonbhadra is often called, villages in the district have been relocated not once or twice, but three times. The air pollution has killed soil fertility and left people wheezing with asthma and itchy with skin diseases.

Gaimon Kanaujia, a 49-year-old primary school teacher in Anpara, was affected by two of the displacements—the first for the Renusagar dam, and the second for the Anpara Thermal Power Plant. He is among those who have spent their entire lives protesting against the pollution, to no effect, he pointed out. “They don’t care if we live or die,” he said, of the local authorities.

When I asked him about the Union environment ministry’s National Clean Air Programme, he was intrigued. He had never heard about it. “If there is a fund for air pollution, we have the first right to it,” he said.

India has the world’s most toxic air, and the ambitious National Clean Air Programme, or NCAP, launched in January 2019, is intended as an effort to tackle this problem. Under the programme, the environment ministry has released around 375 crore rupees ($50 million) to 114 out of a total of 132 non-attainment cities, or cities where the air quality doesn’t meet the national air quality standard.

Separately, the 15th Finance Commission has released Rs4,417, out of a corpus of Rs12,139 crore, as grants to urban local bodies in 42 cities with a population of over a million, to spend on air pollution abatement activities till 2025-’26.

The big-budget to fight pollution

Put together, this amounts to a whopping budget of Rs12,514 crore.

But more than two years since its launch, my travels suggested that the plans of the National Clean Air Programme remain largely on paper. The implementing agencies—state pollution control boards and urban local bodies—typically do not have the capacity to undertake mandated actions; action plans created are often unrealistic, and are copy-paste jobs; and there is a blind spot to areas that have been historically polluted by coal mining and thermal power generation, which help other parts of the country stay electrified.

Anpara, for instance, one of these 132 non-attainment cities, has received only Rs1.24 crore under NCAP, according to a response to a Right To Information request by Scroll.in. Uttar Pradesh, with 17 non-attainment cities, has received Rs60.63 crore in the last two financial years. That these allocations are small is particularly clear from the fact that Rs224 crore of the Rs375 crore, or around 60%, has been budgeted for installing Continuous Ambient Air Quality Monitoring Stations, or CAAQMS, to monitor pollution, as well as to train officials in implementing action plans in these cities. This leaves only around Rs150 crore for actual measures to combat pollution, amounting to just Rs1.3 crore per city.

Anpara has not received anything under the 15th Finance Commission grants, which are only limited to cities with a population of more than 1 million, for now.

The low funding for these places, among the most polluted in the world, also point to what scientists say is a fundamental flaw in India’s approach to the problem: as evident from the NCAP’s plans, it tries to tackle the problem at the level of cities, when, in fact, toxic air recognises no boundaries.

To a large extent, air pollution in cities, especially in the Indo-Gangetic plains, depends on what happens outside them. For instance, the entire Indo-Gangetic plains region, which shares similar meteorological conditions, is essentially a single unit for pollution particles to float in. Scientists call this an airshed.

This airshed records the highest levels of PM2.5 in the country because the Himalayas to the north prevent these particles from moving out of the plains. During winters, when the surface air temperature is lower than the air temperature above, the air stops mixing and becomes stagnant, bringing the entire region from Punjab to West Bengal under a thick layer of stagnant pollution. Further, the loose alluvial topsoil in the Indo-Gangetic plains is prone to get displaced by winds and vehicles, increasing the level of PM10 in the air across the region.

But though scientific studies have established the importance of these airsheds in understanding and tackling pollution, current policy measures remain focused on the political boundaries of cities and states.

According to Sarath Guttikunda, founder of Urban Emissions, a non-government scientific organisation working on air pollution, areas within airsheds have “similar climate, biodiversity and sources of pollution. So, the Indo-Gangetic plains, the Western Ghats, the central plains, including parts of Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh, are all different airsheds.”

Policymakers needed to tackle pollution in each of these airsheds across states, he explained. But “right now there is no mechanism for interstate coordination.”

India’s laws on air pollution control

India has a long history of air pollution control legislation. The Calcutta and Howrah Smoke Nuisance Act of 1863, one of the oldest such legislations in the world, aimed to regulate smoke emanating from the chimneys of Calcutta’s paper mills.

Since then, there have been other such legislations, such as the Gujarat Smoke Nuisance Act of 1963, which focused on that state, and the central Air Prevention and Control of Pollution Act in 1981, which sought to curb air pollution across the country, and set up a governance structure to do this.

In 2009, the Central Pollution Control Board notified the National Ambient Air Quality Standards, which laid out acceptable levels of various air pollutants. These were set at an annual average of 40 micrograms per cubic metre and a daily average of 60 micrograms per cubic metre for PM2.5; and an annual average of 60 micrograms per cubic metre and a daily average of 100 micrograms per cubic metre for PM10.

All these laws and policies should have provided state and national governments with a firm foundation from which to fight air pollution—but they have met with little success.

A policy failure

The failure of these policies was long visible in places like Sonbhadra, but it wasn’t until the winter of 2016 when the national capital began to be smothered with the thickest smog in its recent memory, that the media became interested. Since then, it has devoted significantly greater attention to the problem, at least in Delhi, and the research that surrounds it, which reveals a truly grim picture.

Toxic air killed around 1.67 million people in India in 2019, according to The Lancet’s Global Burden of Disease report. The economic loss due to lost output from premature deaths and morbidity from air pollution was 1.4% of the GDP in India in 2019, or Rs2.6 lakh crore, according to the report.

Yet, as recently as February 2017, then union environment minister, the late Anil Madhav Dave, had told the Rajya Sabha that there was no direct link between air pollution and health. “Health effects of air pollution are a synergistic manifestation of factors which include food habits, occupational habits, socioeconomic status, medical history, immunity, heredity etc of the individuals,” he said.

Later that year, during winter, Dave’s successor Harsh Vardhan told a media outlet that there was no need to panic, since “no death certificate has the cause of death as pollution”.

But the government could not brush aside the issue and the conversation around it forever. “They were in denial, but the scientific data was just too much to ignore,” an entrepreneur working in the air pollution sector said, on condition of anonymity. “On top of this was the increased funding from philanthropies pouring into the air pollution space, up from $5 million in 2015 globally to $44.7 million in 2020,” which was bound to fuel more research into the crisis.

Since 2019, the bureaucracy has filled reams of paper with action plans. There are two kinds of plans under NCAP. The first is a city-level action plan for each of the 132 non-attainment cities. This is supplemented by a more practical micro-plan for each city. For instance, while the Kanpur city action plan states that the city would install water sprinklers and use mechanical sweepers to reduce road dust, the micro-plan for Kanpur identifies hotspots where this activity should be done. All these plans have been framed under an overarching 122-page NCAP guiding document.

Cities also have Graded Response Action Plans, which are aimed at providing immediate relief to people from air pollution in case the air quality deteriorates drastically, through short-term actions like imposing a ban on construction activity and brick kilns and restricting the entry of heavy vehicles into the city.

While the plans appear exhaustive and meticulous on paper, on the ground, whether in Punjab, Uttar Pradesh, or Bihar, I found them to be either unrealistic or non-operational. This partly stems from a basic contradiction in their approach—the plans are meant to kick into action when pollution crosses a certain threshold, but the cities aren’t measuring the pollution levels accurately to start with.

The ground reality in Punjab and Haryana

On the warm evening of Oct. 9, I took a northbound train from Delhi, passing through the harvest-ready paddy fields of Haryana, to reach Ludhiana, Punjab’s largest industrial city. Once there, the air quality monitor showed PM10 and PM2.5 levels at 250 and 275 respectively. These levels were recorded from my hotel room window, situated in old Ludhiana, near the railway station, at around 8pm.

At the same time, the only CAAQMS in the city recorded PM2.5 levels at around 56 and PM10 levels at around 127. Even after calibration (where the values of the low-cost sensor are reduced by around 20-30%), the readings of the city’s monitor were significantly lower.

The reason for this discrepancy was not hard to find: the monitor is placed in the Punjab Agriculture University, one of Ludhiana’s greenest spaces. “People from all over Ludhiana come to walk here,” said Gangneesh Singh Khurana, an industrialist and RTI activist based in Ludhiana, who had accompanied me to the spot. “People are even ready to pay money to have a monthly pass made. And this is the place they have decided to put a monitor.”

RTI responses to Khurana dating back to 2015, when the Ludhiana administration was first planning to install the monitor, show that the administration felt that putting it in a more polluted area would lead to inaccurately high readings.

“How absurd is this?” Khurana asked. “While the city is choking, this monitor, surrounded by trees, away from the congestion of the city will always give readings which are not representative of Ludhiana’s pollution.”

None of the monitoring stations in India, which are all owned and operated by foreign companies, are audited. “There is no third party audit of these CAAQMS,” Khurana said.

The RTI response to Scroll.in stated that Ludhiana had allocated Rs 4 crore for four more air pollution monitors, but Gulshan Rai, chief environment engineer at the Punjab Pollution Control Board regional office, told me that the idea had been dropped. “In a verbal discussion with the central government, we were told to drop the idea of installing CAAQMS and instead install four manual stations,” he said.

CAAQMS show live air quality, and data from them is stored every 15 mins in a server open to the public. In contrast, a manual station only records data twice a week, or 104 times a year. “We were told that the CAAQMS are really expensive, costing around Rs 1 crore, so we should install the manual monitors which cost half of that,” Rai said.

SN Tripathi, professor at the Indian Institute of Technology, Kanpur, and member of the steering and monitoring committees of the National Knowledge Network, an advisory body to the environment ministry set up under the NCAP, explained that the government was trying to build hybrid monitoring networks.

“Cities will have one CAAQMS, and these will be supplemented by manual monitoring stations and low-cost sensor monitors,” he said. While there are standards for the technical specifications of a CAAQMS, right now no such standards are available for low-cost sensors. “We are doing a study on various low-cost sensors, which will be published soon,” Tripathi said. “I hope the government will consider the study and come up with a guideline for standardising the low-cost sensors.”

Incomplete studies and inadequate tech

India’s fight against pollution is also hampered by the fact that many of the city action plans were created without performing source apportionment studies, or emission inventories.

Source apportionment studies, usually done with two seasons’ worth of air pollution data, identify and assess the contribution of sectors that are polluting a city. An emission inventory, meanwhile, is a compilation of how much pollution each individual polluter, like a thermal power plant or a garbage fire, is emitting into the airshed. While an air quality monitor can determine that the air in a particular location is bad, a source apportionment study, along with emission inventories, can provide vital information on who is polluting the area, and are thus important tools in the policymaker’s arsenal in combating air pollution.

In the absence of these analyses, there remains considerable uncertainty in estimating the pollution released by different sectors, like transport, industry, agriculture and the domestic sector, and from different sources, like road and windblown dust. This makes it difficult to identify which sectors and sources to prioritise through regulation.

The studies done so far vary widely in their estimates of pollution emission by different sectors. A recent report by the think tank Council on Energy, Environment and Water noted that the estimation of the contribution of domestic sources to India’s PM2.5 pollution load varies from 27% to 50% across different emission inventories, done by international organisations as well as Indian institutions like IIT Bombay and TERI.

There are multiple reasons for this wide variation. For one, different inventories use different definitions of each sector—for instance, some include diesel generators in the domestic sector, and others in the agricultural sector. They also use different emission factors—the measure of how much emission is caused by one unit of fuel in a particular sector, using a particular technology. In 2011, the CPCB had standardised a set of emission factors, but these don’t cover the full range of technologies and fuels used today.

Under NCAP, a national emission inventory was to be created by 2020, but this has yet to happen.

Moreover, the calculation of pollution levels, largely dependent on CAAQMS, focuses only on the presence and size of particulate matter, and not on what these particles are made of. Hazardous chemicals like dioxins, furans, and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, can have serious and differing impacts on health, but right now they are collectively categorised as particulate matter. As a result, the health risks directly associated with the toxicity of the chemicals that make up particulate matter, which can be identified through chemical characterisation, are overlooked.

For instance, PM10 levels of 150 are uniformly considered worse than PM10 levels of 100, even though the latter can be more harmful to the health if the air contains dioxins, and the former contains dust.

“We have the technology where low-cost sensor monitors can also record the chemical characterisation of the particulates,” Tripathi said. “But this chemical characterisation will be the next step. First, we have to build these monitoring networks for particulate matter.”

Ozone is another pollutant that is being overlooked by this fixation on particulate matter. Although ozone levels are currently within the standards in all non-attainment cities, studies have found that in Delhi, during the lockdown, while PM levels declined, ozone levels increased.

“It is overall air quality that matters, not only PM levels,” said Dhirendra Singh, CEO and founder of Airshed Planning Professionals Private Limited, a Kanpur based firm that provides technical services around air pollution.

“We should learn from these recent studies conducted in China and other parts of the globe and derive a sustainable air pollution control plan for particulate matter and gases both.”

In the absence of inventories, many of the city plans to fight pollution are based on estimates or even outdated figures. Though there are new studies, most plans have not been updated to incorporate them.

The Ludhiana action plan, for instance, states that around 16% of the city’s pollution is caused by biomass and garbage burning (which includes stubble burning) and that the top contributors to the city’s pollution load are industries (35%) and road dust (28%). These figures were arrived at during a source apportionment study done in 2012.

But a more recent study by Urban Emissions, published in 2017, showed that after industries, the second-biggest source of pollution in Ludhiana was the transport sector, not road dust. More significantly, around 41% of the city’s pollution originates outside its boundaries. Of this, brick kilns account for 14%, and stubble burning for 10%.

“There are no provisions in the plan to deal with these brick kilns outside the city limits, but we monitor them as part of our regular duties,” said Gulshan Rai, the Chief Environment Engineer at the Ludhiana regional office of the Punjab Pollution Control Board. Rai heads a team of seven that has to monitor around 10,000 industries in Ludhiana. Combating air pollution is now an added task.

Further, the city’s action plan categorises stubble burning under pollution from garbage and biomass burning, and thus does not give the problem the focused attention it needs.

This is reflected in the absence of solutions to tackle them in the action plan. The only reference to stubble burning in the plan is a reiteration of an existing framework for monitoring and penalising farmers for burning stubble. For assistance, the farmers have only one scheme to rely on, which provides subsidised equipment to help them dispose of the stubble. The primary focus of this scheme, which was put in place in 2017, wasn’t even regional pollution in Punjab—rather, its main aim was to reduce pollution in Delhi. Since 2018, the Punjab government has spent around Rs1,045 crore on subsidies on farming equipment that can clear stubble.

I met Raspinder Singh, who is in his mid-thirties, in his village, Sherpur Kalan, some 50 km from Ludhiana, on a day in early October, when stubble burning was just beginning. A few patches of smouldering black could be seen among fields of golden ripe paddy. As the pollution was increasing, so were Raspinder’s problems.

“I have a skin disease and when the pollution levels spike here, the itching becomes really bad,” he said. His grandfather, too, has trouble breathing. While Raspinder and his family, who own 40 acres, have stopped burning stubble, many small farmers did not have the means to adopt an alternative to stubble burning.

Karandeep Singh, who owns four acres of land and grows potatoes during the Rabi season, believes that the government hasn’t addressed the fact that managing stubble without burning is too great a financial burden on farmers.

“If I do not burn the stubble, then after harvesting using a combine harvester, I have to use a rotavator to remove the stubble, then use an MB plough to upturn the soil, leave the land for 10 days, then use the rotavator again to remove any remaining stubble,” he said.

“All this not only takes time, but with the prices of diesel touching the sky, it costs me around Rs3,000 to Rs4,000 per acre. Why should I pay that money?”

Some experts believe that farmers would adopt methods other than burning to remove stubble if they were compensated for the work needed. According to a member of the Punjab Pollution Control Board, who spoke on condition of anonymity, this “won’t take more than Rs2,000 crore to Rs2,500 crore in all of Punjab.” But, he added, “while providing thousands of crores of relief to industries, it seems this cost to support farmers is too huge for them.”

Along the Gangetic plain in Uttar Pradesh

On the evening of Oct. 15, just before the effigies of Ravanas went up in flames to mark Dussehra, my air quality monitor recorded PM2.5 and PM10 levels at 220 and 233 respectively in front of my hotel in Kanpur.

With the metro line construction underway, along the stretches of the road next to the construction activity, the traffic was choked and the low-cost sensor recorded PM 2.5 and PM 10 levels of 266 and 332 respectively.

Yet, as mandated under the action plans, there were no green sheets over these under-construction structures to prevent construction dust from mixing into the atmosphere. Though the city’s action plan envisions electric buses on the roads, I did not see any.

A few kilometres away was IIT Kanpur, a key constituent of the NCAP’s National Knowledge Network. While the levels of particulate matter in the green and sprawling IIT campus are much below the standard levels—my monitor recorded 43 for PM 2.5 and 56 for PM10 – the rest of the city continues to breathe polluted air.

The Kanpur Municipal Corporation’s Project Cell, which deals with air pollution, is the recipient of Rs 75 crore under the 15th Finance Commission grant for 2021-’22. But an official working with the Project Cell complained: “We are working with 50% staff. There is also a lack of technical expertise in dealing with air pollution.”

A city-level implementation committee that includes members of the corporation, the Kanpur regional office of the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board and IIT Kanpur, meets fortnightly to discuss air pollution measures and improve the technical capacity of the corporation. “IIT Kanpur and the pollution control board officials are charged with capacity building,” the official said. The technical information that had been shared with the corporation, he added, included “how to sweep roads properly so that dust doesn’t spread”.

Like in Uttar Pradesh, in Bihar, too, the agencies responsible for fighting air pollution are short-staffed.

The State Pollution Control Board is functioning at a 60% staff capacity, according to Ashok Ghosh, the chairperson of the board, who also volunteers as a scientist at the Patna-based Mahavir Cancer Sansthan, a cancer hospital for the underprivileged. “We are in the process of getting more people,” he said.

As a capital city, Patna is better off than other cities. It was also the only city where I saw electric buses plying the roads. The city has CAAQMS installed in six locations. Bihar’s two other non-attainment cities, Muzaffarpur and Gaya, have three each and do not have electric buses. “We are in the process of installing at least one CAAQMS in 22 of the 38 districts of Bihar, and starting electric buses in Muzaffarpur and Gaya,” said Ghosh.

The central funds were meant to “plug the gaps in the governance structure” of urban local bodies and state pollution control boards, said Vivek Tejaswi, deputy director of Asian Development Research Institute, a developmental think tank based in Patna.

“All these departments function with a staff strength of 50% to 60%. Instead of hiring more people, the focus here is on increasing capacity,” he said. “How can you increase the capacity of a person who is already overburdened with work?”

This is resulting in instances of shoddy work. Uttar Pradesh, India’s most populous state, has 17 non-attainment cities, the highest of any state. A study of all the action plans under NCAP in the country by the Council on Energy, Environment and Water found that 16 of these cities in Uttar Pradesh “have identical plans, each with the same 56 actions for transport, road dust, vehicles, waste burning, industries, and construction and demolition.”

But these plans are rarely put into place, even in a major city like Patna. “Taking actions like shutting down industries, stopping construction activities, many of which are backed by influential people, will bring pressure on the officials, therefore these measures are never taken. No one wants to stick their neck out,” said a former Bihar State Pollution Control Board official on condition of anonymity.

Ghosh pointed out that for a graded plan to work, “it requires a lot of micro-level information and technical expertise. We are in the process of getting this expertise and soon will start with the implementation of the plan.”

While the city’s action plan talks of curbing pollution from brick kilns, there is no word on sand mining and the pollution originating from its transportation. “If you look at the plan, it focuses on the low hanging fruits, things which are easy to handle,” Tejaswi said. “Activities like sand mining are dominated by big, influential players and touching them is difficult. Similarly, the plans are silent on improving the emissions reduction technologies in industries.”

Nowhere are the absurdities in city action plans as stark as in Anpara.

A plan too good to be true

The regional office of the Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board here has four officials, who have to oversee a staggering 2,000 industries across the districts of Sonbhadra and Mirzapur, spread over an area of 11,300 sq km. For this, they share one rented Mahindra Bolero between them.

Within Anpara, which is a Nagar Panchayat, a classification that lies between a village and an urban area, three officials have been made members of the Air Quality Monitoring Cell. But the panchayat doesn’t have any funds to undertake any pollution reduction activity.

There is a stark disconnect between what the city’s micro-plan suggests and the reality on the ground. For instance, while very few people have plastered houses here, the city’s micro-plan talks about setting up multilevel parking.

“You read the Anpara plan and it feels like it is talking about London or Tokyo,” an Uttar Pradesh Pollution Control Board official said on condition of anonymity.

“There are no roads there and the plan talks about mechanical sweepers and water sprinklers. These plans have all been made by people who have never come here. They have copied the plans from other places,” the official said.

In Anpara, the action plan acknowledges that the area’s thermal power plants are a major source of pollution. But the Union environment ministry has been trying to put off imposing stricter emission standards on thermal power plants since 2015. The ministry had notified standards for particulate matter, sulphur dioxide and oxides of nitrogen in 2015, with which thermal power generators had to comply by 2017. But since then, the ministry had amended the notification thrice—most recently on April 1, this year—to delay the compliance deadline. Now all the plants have to comply with the new norms by 2025.

In the meantime, people suffer. “Of all the people coming to the Primary Health Centre, Anpara, around 50% are suffering from air pollution-related diseases and the other 40% are suffering from diseases arising from high levels of chloride, fluoride and mercury in the water,” said Ajeet Singh, a doctor at Anpara’s Primary Health Centre. Though there haven’t been any specific studies to establish the cause, Singh believes that the “thermal power plants are the cause behind this.”

Scroll.in sent out queries about the flaws in the government’s approach to tackling pollution to officials in Anpara, Ludhiana and Kanpur, as well as to the central government’s environment secretary. As of the time of publishing, no responses had been received.

Anpara also underlines the fundamental flaw at the heart of the National Clear Air Programme. It lies within what the central pollution board notified in 2013 as the Singrauli Critically Polluted Area, but the Anpara action plan focuses only on the city.

When I visited Shakti Nagar, 20 km from Anpara, bordered by the Khadia coal mine operated by the Northern Coalfields Limited on one side, and the Singrauli Super Thermal Power Plant on the other, almost every other house had people suffering from respiratory or skin ailments. The dust from the mine and the coal fly ash from the thermal power plant blanketed everything. In the afternoon, my monitor started recording levels above 400 of both PM10 and PM2.5, as people lit coal to make food.

“I got a cylinder under the Ujwala scheme, but now with the gas prices crossing Rs 1,000, I can’t afford it,” said Ashok Kumar, whose father passed away after battling asthma after 20 years, just like his mother a few years earlier. “My son collects the coal which drops from the trucks carrying it and it is sufficient to make food and doesn’t cost anything.”

Chilkadand village, next to Shakti Nagar, has been relocated multiple times. The village has no government land or private agriculture land – its residents depend entirely on work at either the coal mine or the power plant. “We don’t get MGNREGA funds because there is no government land to work on, all land belongs to either NTPC or NCL,” said Heeralal, sarpanch of Chilkadand panchayat. “People don’t have enough to eat here and that makes them vulnerable to diseases.”

He added that if the government is really serious about reducing pollution, then it should formulate special plans for places like Chilkadand, which are paying the price for keeping India’s lights on. “More than Rs10,000 crore to deal with air pollution and they give us nothing!” he said. “If they gave even a fraction of this to us, we would cook using clean fuel, be able to afford proper healthcare and live a better life.”

This piece was originally published on Scroll.in. This reporting is made possible with support from Report for the World, an initiative of The GroundTruth Project.