Modi is enabling a handful of very large players to run India’s economy

In December 2020, NITI Aayog’s chief Amitabh Kant was attacked for saying that India had “too much democracy.”

In December 2020, NITI Aayog’s chief Amitabh Kant was attacked for saying that India had “too much democracy.”

However, another part of his speech went relatively unnoticed. Kant said: “In India we are too much of a democracy so we keep supporting everybody.” He went on to elaborate, “For the first time in India a government has thought big in terms of size and scale and said we want to produce global champions. Nobody had the political will and the courage to say that we want to support five companies who want to be global champions. Everyone used to say I want to support everyone in India, I want to get votes from everyone.”

What he was saying in essence was that the government of India would back a very small set of elite firms. This was being done in two ways. One called “formalisation” and the second through blocking foreign competition in crucial sectors (“import substitution”).

The formalisation theory was that India had too many small companies and this was inefficient. It should instead have only a handful of very large players running its economy, and these giants would then compete with large firms around the world.

So what could the government do to make this possible?

It would try and make it difficult for the small- and medium-sized industrialists to exist. This is also called formalisation because it assumes that the small- and medium-sized entities in business are generally inefficient and tax thieves. They cheat the government by operating in cash.

To make their existence difficult, if not impossible, the first step was to remove cash from the economy. This was done on Tuesday, November 8 2016. Businesses that depended on cash transactions, even if they were legitimate ones, were not able to operate for weeks and were hampered for months. The large businesses were not affected because they could use electronic transfers, just as the upper class in the metropolitan areas managed with their credit and debit cards.

The second stroke against the small and medium sector was GST, which was designed in a way as to require significant expertise in-house or on contract for compliance. The repeated and frequent filing of returns and the managing of the digital system meant that once again a large number of people exited from businesses that became unviable because of the added cost or simply because people could not cope with the new complications and chose to do something else.

Who benefited from the exit of the small and medium businesses? Again, the large ones.

The third stroke was the lockdown of 2020, which broke the back of the small and medium sector, which had neither the cash reserves to be able to deal with such a blow nor the ability to get their staff to “work from home.”

Everything that appeared to be puzzling to many about the Modi government’s economic policy appears to make sense after we consider what it is deliberately doing to this nation. Modi’s former advisor and enthusiast Arvind Panagariya had complained about the Atmanirbhar Bharat programme, saying that it was merely import substitution and had failed before. But what if it was deliberate to ensure that some industrialists could sell their goods at a higher price to Indians than the cheaper imported products from the competition?

…

Atmanirbhar Bharat privileges the industrialist over the consumer, but that is not the way that it is advertised. Who does the policy seek to make atmanirbhar? It is not the consumer or the citizen, who must pay more. It is those selected favourites of the government who have been tasked with winning, while the rest are left deliberately to fail.

Let us take this a step further and see if what Kant says the Modi government is intent on doing has worked.

An analysis of 3,220 listed non-finance companies revealed that in the last quarter of the calendar year 2020, the companies in the bottom 70% showed a fall in sales which they surrendered to the top tiers. Sales had been down by 6.7% in the September 2019 quarter, down 5% in the December 2019 quarter, down 9.8% in the March 2020 quarter (just before the lockdown).

In the first quarter post lockdown ending June 2020, net sales were down 39%. In the September 2020 quarter, down 10%, and in the December 2020 quarter, down about 1%. In a declining market, the large fish were taking a bigger share. And they were profiting.

The share of corporate taxes in government revenue fell to its lowest in a decade after the tax cuts on corporates and the tax rise on petrol and diesel. The ratio of corporate profits to GDP also hit a 10-year high.

The Economist reported that Gautam Adani’s net worth went up by 750% in 2020. Mukesh Ambani’s went up by 350% in that year—the year in which India’s GDP shrank and crores became destitute. In the first five months of 2021, Adani’s wealth grew by $32 billion (over 2 lakh crore rupees) and he became Asia’s second-richest man, behind Ambani. The money was flocking to where it was felt to be winning in the long term under Modi.

Amid the pandemic, in 2020, India added 55 new dollar billionaires (individuals worth more than Rs7,000 crore), more than one every week. This was a 45% jump compared to the year before and took the total number of Indian billionaires to 177.

The Economist stated that “most alarmingly, in India some of the rich have become super-rich by using their heft to crush smaller competitors and thus corner multiple chunks of the economy. The tilt in fortunes has rewarded not so much technical innovation or productivity growth or the opening of new markets as the wielding of political influence and privileged access to capital to capture and protect existing markets.”

This is, of course, deliberate.

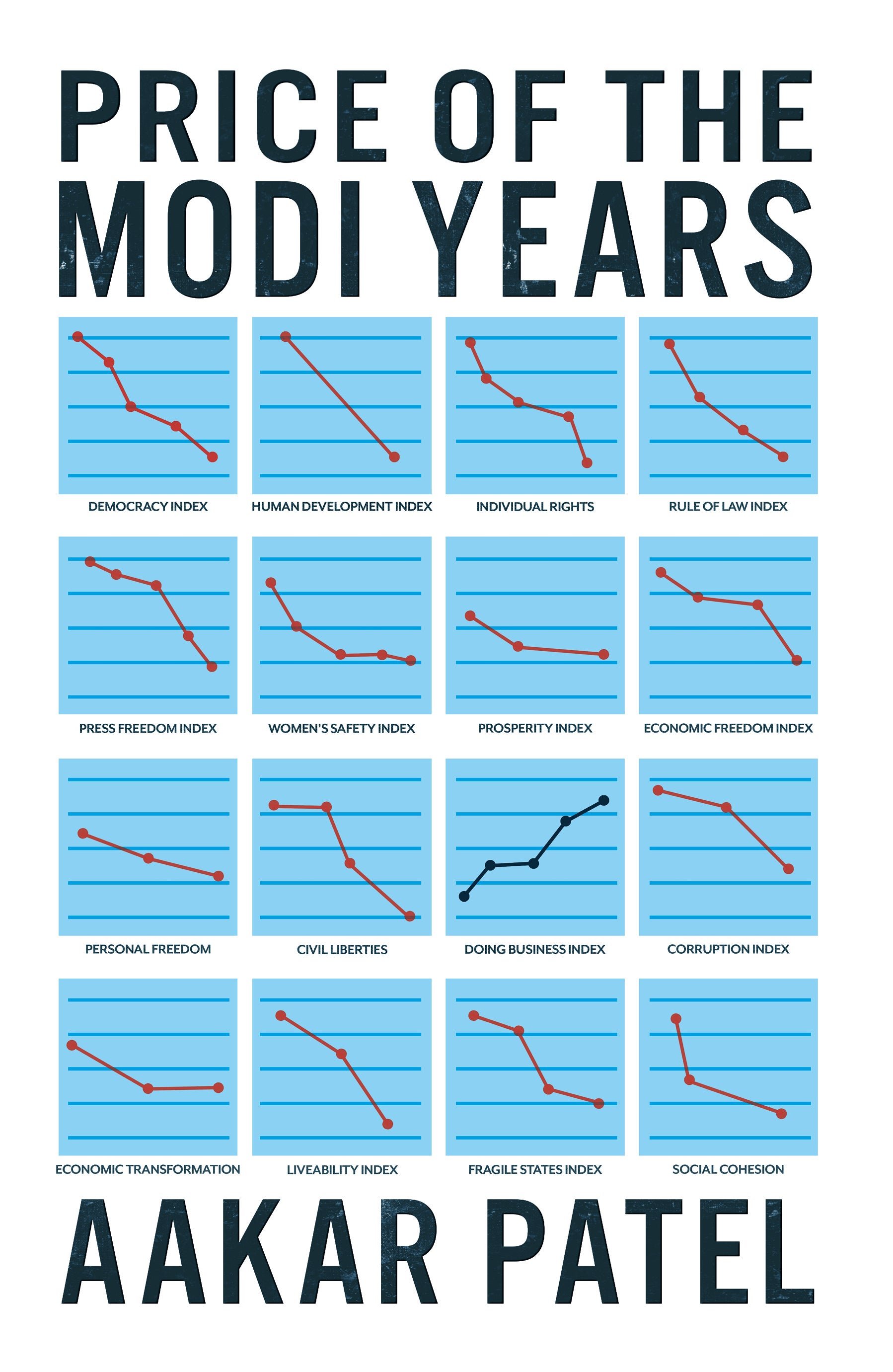

Extracted with permission from Price of the Modi Years by Aakar Patel, published by Westland Non-Fiction, an imprint of Westland Publications, November 2021. We welcome your comments at [email protected].