India’s biggest bank fraud is a telling tale of public money put in jeopardy

As the Enforcement Directorate on Wednesday (Feb. 16) registered a case of money laundering against Gujarat-based ABG Shipyard based on the complaint of the State Bank of India (SBI), the company has been described as being involved in “India’s biggest bank fraud.” The company’s chairman, Rishi Kamlesh Agarwal, was questioned by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) for defaulting on loans amounting to 22,842 crore rupees ($3.03 billion) that ABG Shipyard took from 28 banks.

As the Enforcement Directorate on Wednesday (Feb. 16) registered a case of money laundering against Gujarat-based ABG Shipyard based on the complaint of the State Bank of India (SBI), the company has been described as being involved in “India’s biggest bank fraud.” The company’s chairman, Rishi Kamlesh Agarwal, was questioned by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) for defaulting on loans amounting to 22,842 crore rupees ($3.03 billion) that ABG Shipyard took from 28 banks.

The loan account had been declared as a non-performing asset (NPA) in July 2016, after futile attempts at restructuring it by the SBI and a failure to recover the money through the process laid out under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC). It was declared a fraud in 2019.

Of the 28 institutions that are owed money, 13 are public sector banks, three are international subsidiaries of public sector banks and three are government-owned entities.

Two complaints

SBI had filed two complaints with the CBI about the bad loans, once in November 2019 and then in December 2020. While finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman has defended the long delay in prosecuting Agarwal and his associates, it is rather disturbing that the CBI took one-and-a-half years to “scrutinise” the matter even after the second complaint by the SBI. By this time, the bank had already given the clarifications that were sought after the first complaint.

At a time when India seems to be ready to hand over its railways, highways, ports, and pipelines to private hands on lease, these frauds come as a rude reminder of how the government is gambling with the savings of ordinary citizens.

But before we proceed any further, we need to comprehend the size of this scam—which involves public money.

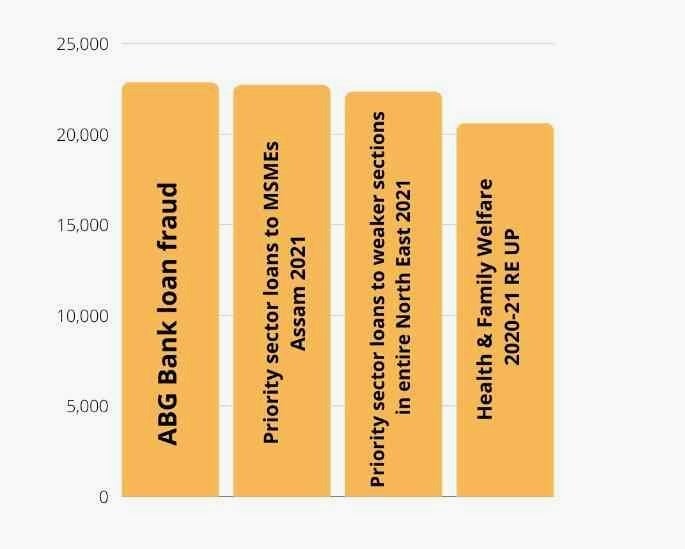

In the pandemic year of 2021, the revised estimate of the Uttar Pradesh government’s spending on health and family welfare for its 235 million people (who form 16.5% of India’s population) was Rs20,582 crore, which is lower than the amount of money in the ABG bank fraud of Rs22,842 crore.

That year, the total loan amount disbursed by all scheduled commercial banks to the 1.78 million micro, small and medium enterprises (MSME) account holders in the state of Assam as priority sector lending amounted to Rs22,698 crore. Again, this is slightly less than the loan fraud amount of ABG Shipyard.

In the same period, the total loan amount disbursed by scheduled commercial banks as loans to weaker sections under the priority sector to the 4.41 million account holders in the entire northeastern region (comprising the states Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, Manipur, Meghalaya, Mizoram, Nagaland and Tripura) amounted to Rs22,329 crore. That is still Rs513 crore less than the loan fraud amount involving ABG Shipyard.

But then again, it is not about Rishi Agarwal or businessman Vijay Mallya, who owes Rs10,000 crore, or Nirav Modi, accused of fraud amounting to Rs11,356.84 crore. It is about a deliberately flawed lending policy that has added to the mounting fraud loans and NPAs over the years.

It is pertinent to note that the total fraud loans in 2020-21 in India amount to Rs1.37 lakh crore, which accounts for 99% of all bank frauds.

Again to put this in perspective, the figure for fraud loans is higher than the total agricultural loans disbursed by all scheduled commercial banks to just over 7.1 million account holders in the state of Uttar Pradesh as priority sector lending in the pandemic year of 2021. That amounted to Rs99,083 crore.

Loans to MSMEs in Uttar Pradesh amounted to Rs1.05 lakh crore.

It is also substantially higher than the Centre’s revised estimate of Rs86,000 crore for the ministry of health and family welfare for the year 2021-22.

As per Reserve Bank of India data sought in an RTI, as of March 2021, Indian banks have reported total frauds amounting to Rs4.92 lakh crore.

By far the biggest chunk of frauds has been borne by the public sector banks. Looking at the numbers for 2019-21, public sector banks account for Rs2.94 lakh crore of frauds while the share of frauds for private sector banks is Rs86,355 crore. This is despite the fact that in 2020-21, the number of frauds under the private sector was much higher (3,710) than in the public sector (2,903).

The larger amount of fraud in public sector banks is linked to its higher corporate exposure to risky sectors of the economy, something that has been deliberately encouraged by the government to support its corporate “champions.”

Looking at NPAs

The story gets compounded when we take stock of NPAs. In March 2021, the NPAs of India’s scheduled commercial banks stood at Rs8.35 lakh crore. Of this, about 77.9% were the loans that remained unpaid by larger corporate borrowers, mostly from the public sector banks.

In March 2021, the finance minister informed the Lok Sabha that the scheduled commercial banks have written off loans worth Rs5.85 lakh crore during the last three financial years, while recovery has been paltry, at just over Rs68,000 crore.

The process of large-scale, long-term lending of public money through commercial banks has been facilitated by the “ease of business” pressures of India’s market fundamentalist-driven system. Instead of keeping such mega-infrastructural lending in the domain of development finance institutions, the hard-earned savings of ordinary Indians were unlocked for speculative, risky and sometimes fraudulent ventures.

It is the resultant unbridled investments in risky large-scale projects in the private sector that has cumulatively compounded these NPAs.

Days before news of the ABG Shipyard’s loan fraud appeared in the headlines, finance minister Nirmala Sitharaman presented her budget speech. She made only a passing reference to the NPA crisis, saying that the bad bank—the National Asset Reconstruction Company to resolve cases involving large bad loans—is up and ready.

However, far from addressing the fundamental issues concerning regulating and monitoring corporate loans, lending policy or recovering bad loans, the National Asset Reconstruction Company will merely be shifting bad loans from one book to another.

This seems like a desperate move to clear balances, six years after the IBC has been in operation to deal with the NPAs of large corporate borrowers. But recovery by lenders through the Code process has not been as bright as was hoped. In 2017-18, lenders recovered 51.3% of their claims but the figure came down to 46.4% the next year. It dropped further to 16.8% in 2019-20. In 2020-21, lenders recovered only 28.5% of their claims.

Claims ring hollow

ABG Shipyard in fact was one of the initial “dirty dozen”—the first 12 cases—referred to the IBC process in June 2017. But it remained unresolved for nearly five years. There were several failed attempts to liquidate the company. The first auction was attempted in September 2019 and the fifth in August 2020, but there were no buyers.

In December 2020, the National Company Law Tribunal allowed the company to be liquidated.

This in itself speaks volumes about the process of the IBC and its “time-bound recovery” claims.

Rather than playing with public money by writing off large corporate bad loans, again and again, India needs to strengthen loan recovery processes, introduce stricter regulation and lending policies, regular audits, and separate long-term infrastructure lending to private companies from commercial banking.

Instead, the government seems inclined to favour big corporations, giving them massive tax cuts and write-offs on bad loans while passing the burden of their frauds and taxes onto the people. We must follow the ABG Shipyard scam closely as it unfolds. We must not only count the zeroes, but also hold those responsible to account.

This post first appeared on Scroll.in. We welcome your comments at [email protected].