Investors working to spark social change in India suffer from herd mentality

Impact investors—people who like to make money and look good while doing it—are hot on India.

Impact investors—people who like to make money and look good while doing it—are hot on India.

It is, after all, a country with innumerable problems in education, healthcare, sanitation and other fundamentals that there is so much good change to be made by carefully investing in technologies and companies or nonprofits that are helping turn things around.

Naturally, India is among the largest destinations for impact investors. But those in this field, committed to sparking social change, seem prone to herd mentality just as much as mainstream investors. They are putting too much money in one, relatively safe, tried and tested model—microfinance.

Funds in this space have been active since the mid 2000s. Intellecap, a consultancy for social enterprises, found that since 2001, $1.6 billion have been invested in companies in India’s social enterprise sector.

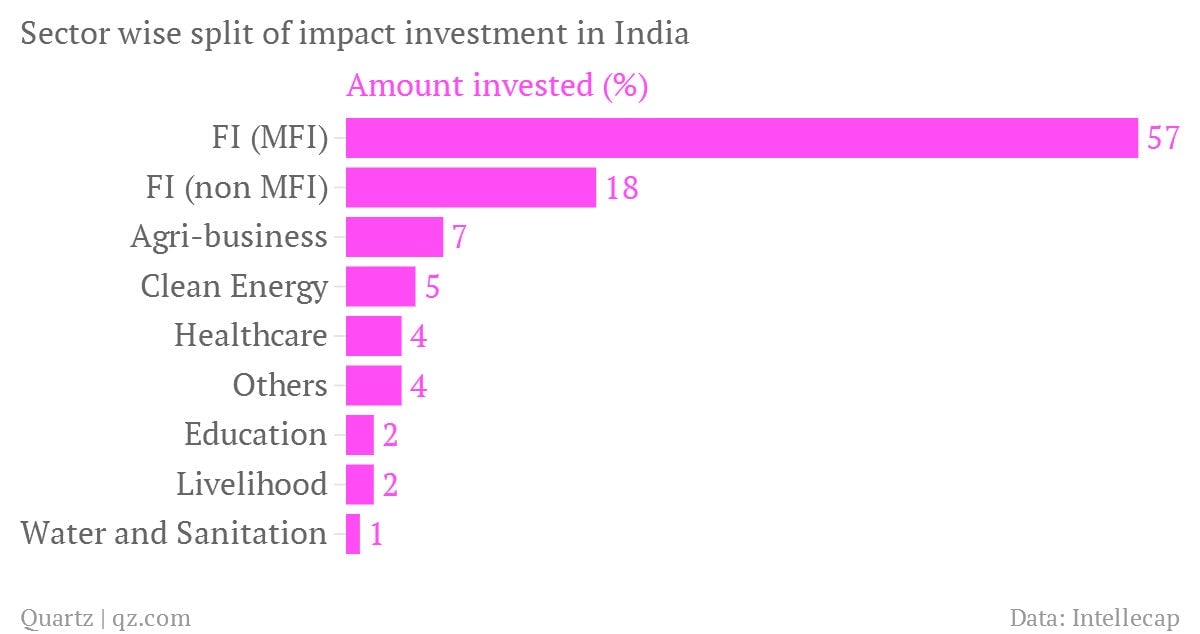

Not a small sum. However, 60% of that has gone to only 15 enterprises. And 70% of the total, or about $1.1 billion, was deployed in enterprises in the financial inclusion space, which accounts for only 21% of the social enterprises in India. It’s practically an investment community that is dedicated to micro-lending.

Other sectors like agri-businesses attracted 7% of the capital. Clean energy and healthcare followed close after, attracting 5% and 4% of the capital, respectively.

Impact funds claim they are taking on higher risk and are more patient investors compared to mainstream investors. In light of this data, it is a claim that is hard to swallow. Paul Basil, founder and CEO of Villgro, a social enterprise incubator, says: “There is only a level of risk that these funds can take. The microfinance space, which has attracted most of the funding, is a model that has been worked on for over two decades.” Basil notes that there is a lack of scalable enterprises that can be backed by impact investors in India.

The interest in microfinance is also sparked by the sector’s ability to offer a viable exit. The report found that there have been only 15 exits at a premium by impact investors in India. Of this 10 exits came from the microfinance sector. “In the social enterprise space, microfinance is the only sector that has so far seen an IPO. While the sector had a shaky phase in India, the sector hasn’t stopped growing and therefore still attracts a lot of capital,” said Saurabh Lahoti, director at Ennovent, a social enterprise accelerator.

Microfinance companies tend to be tech-centric businesses that need a lot of capital. So funds are able to deploy larger amounts of capital with these companies. But it is not as if other sectors don’t need capital or technology innovation. Because there isn’t a proven model, funds are reluctant to back them. “There is a certain amount of herd mentality. There are clearly not enough risks being taken,” said Prashant Chandrasekaran, associate vice president of consulting at Intellecap.

So the next time you run into an impact investor who talks up the wonderful ways in which their money is being put to work in India’s villages, ask them about their portfolio spread outside the financial inclusion space.