A Bangalore accountant says he’s invented a way to clean the Ganga

A Bangalore-based chartered accountant says the seeming impossibility of cleaning the Ganga is a matter of mastering the underlying chemistry, and he has a solution to the problem. When dissolved in polluted water, his invention promotes the growth of a beneficial kind of algae, which releases oxygen into the water as it grows. More oxygen means more aerobic bacteria, which breaks down pollutants in the water.

A Bangalore-based chartered accountant says the seeming impossibility of cleaning the Ganga is a matter of mastering the underlying chemistry, and he has a solution to the problem. When dissolved in polluted water, his invention promotes the growth of a beneficial kind of algae, which releases oxygen into the water as it grows. More oxygen means more aerobic bacteria, which breaks down pollutants in the water.

With new prime minister Narendra Modi pledging to clean the Ganga—he represents Varanasi in the Lok Sabha—the enormity of the task has come into focus. The tourism ministry has already allocated Rs18 crore (about $3 million) to renovate the ghats of the pilgrim city.

Like the Ganga, Bangalore’s lakes have been host to untreated wastewater and sewage for many years now. And like the Ganga, the consequences include algal blooms, stenches, mosquito infestations and drinking water contamination. These foul waters have been the laboratories of T. Sampath Kumar, a chartered accountant by training, who is also the inventor, producer and sole supplier of a proprietary nutrient he calls Nualgi—Nu for new and algi for, well, algae.

Fishermen in Bangalore are using his concoction of nutrients to clean their hunting grounds so that fish livestock is replenished. Kumar believes the mechanism that works in the lakes of Bangalore can work in the mighty Ganga.

Kumar’s technique works by kick-starting the foundation of the aquatic food chain. He feeds a mixture of nutrients to diatoms—the most basic, single-cell life form found in ponds, lakes, rivers and oceans. As the algae formed by diatoms grow, they release oxygen into water. Oxygen sustains all other life in water, including aerobic bacteria, which can efficiently break down organic matter and clean the water.

Untreated, sewage-filled water has too much nitrogen and phosphorous, which helps blue-green algae grow. This slimy variety of algae allows the growth of anaerobic bacteria, which break down organic matter only partially, leaving behind a host of pollutants and releasing malodorous gases like hydrogen sulfide and methane.

The major ingredient in Nualgi is silica in nano form. Silica, which constitutes the cell wall of diatoms, forms tiny containers for various elements in the Nualgi mixture—iron, magnesium, zinc, copper, sulphur, manganese and calcium. Kumar says that when Nualgi is added to water, it restores the nutrient balance and allows diatoms grow and oxygen to be pumped into the system. One litre of Nualgi, he says, can purge 4 million litres of water of its contaminants.

Kumar has used the lakes of Bangalore and Hyderabad to test the product, and he holds a US patent (No. 7585898) for it. With no scientific training and no institutional support, he has tweaked his formula through trial, error, and observation.

In 2011, Kumar sent Nualgi from a small manufacturing facility in Bangalore to clean a three-acre duck pond in New York state. His company, Nualgi Nanobiotech, continues to export the product to a couple of US firms that undertake water treatment projects. Kumar has also developed a crop spray using the same technology. Last year, he says, he sold about Rs 1 crore ($170,000) worth of the two products, priced at Rs1,500 ($25) per bottle, and about half the sales were exports.

Kumar says he has submitted his invention for analysis at several government and research institutes. Bangalore University zoologist and water quality expert M. Ramachandra Mohan visited one of Kumar’s test lakes back in 2009 and was surprised by what he saw—a cleaner looking lake and healthier looking fish. He took Nualgi back to his lab. “We used to feed the fish and see what happens. We saw the fish grew to a bigger size than otherwise. So the product is being converted into proteins,” Mohan said. But he was also concerned by the sudden bloom of diatom algae. “The dead algae sediment add more calcium to the water but otherwise there is no problem.” Mohan continues to test Nualgi in his lab for long-term effects.

Kumar, however, shrugs off the importance of a stamp of approval saying, “Testing is only for your satisfaction. Here you want a particular job done and it (Nualgi) is working for that job.”

Kumar is now looking towards the Ganga with interest.

The Ganga is both the source for water and the receptacle for sewage for major cities and towns, including Haridwar, Allahabad, Varanasi, Patna and Kolkata. Some 4.4 million people live along the river and it accepts industrial discharge from Kashipur, Moradabad and Meerut.

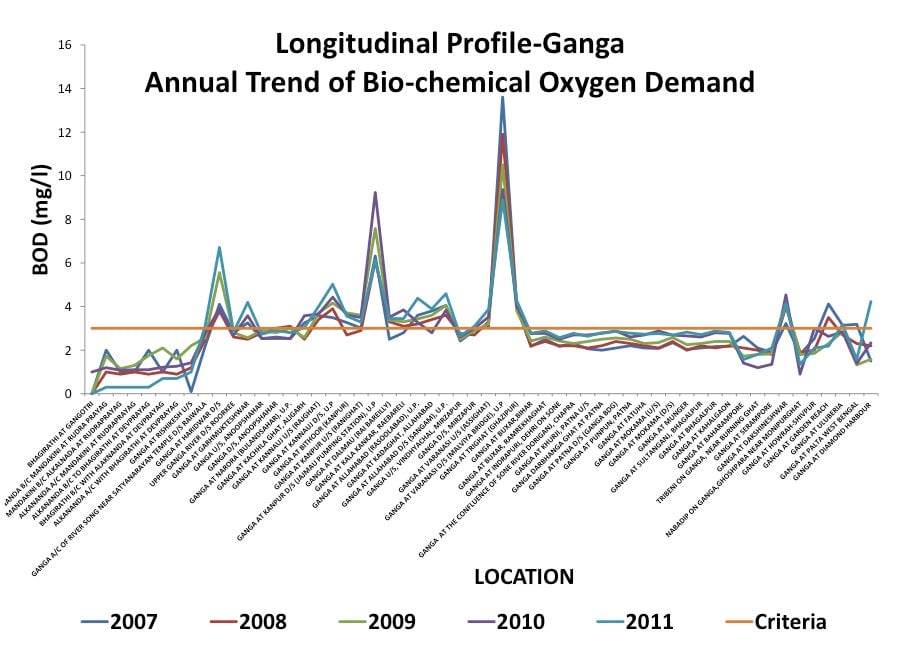

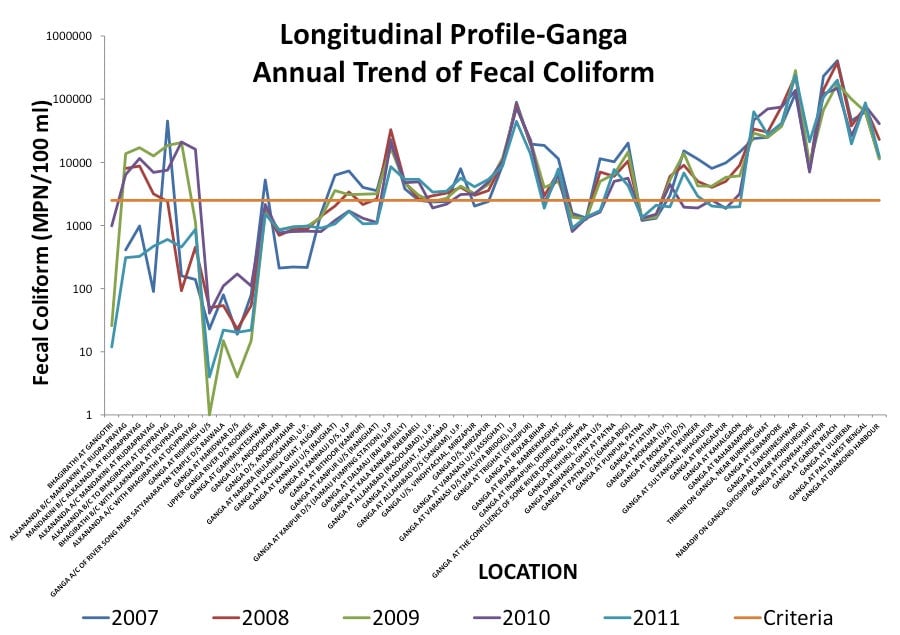

A Central Pollution Control Board assessment of the river between 2007 and 2011 revealed how oxygen-starved it is as it passes through cities. Fecal coliform levels take off as sewage accumulates in the lower reaches.

Enter Nualgi. “Millions of villages, town and cities through the length are sending their sewage to the Ganga. Distribute this product to all of them. Estimate the total volume, if you are adding 4 million liters (of sewage) everyday, add one liter (of Nualgi) to that. Let it go into the Ganga,” Kumar says.

One of the most polluted stretches is near Kanpur and its tanneries. Rakesh Jaiswal, founder of the Kanpur-based NGO Ecofriends, has been campaigning for a clean Ganga for the last 20 years. Jaiswal’s solution for the river is a conventional and widely supported view. “The amount of water flowing through the original course of the river should be increased,” he says, referring to the irrigation canals upstream that have left Ganga depleted in the middle and lower reaches without the necessary power to wash away the muck. “There are enough laws, rules and regulations but those have to be implemented. Industries should be disciplined,” says Jaiswal.

But Kumar says it doesn’t matter whether the Ganga is flowing, trickling or stagnant, as long as you have Nualgi. “Let the water be there,” he says. “You can clean it.”