Installing toilets might not be enough to protect India’s women from rape

The headlines have been clear in assigning blame:

The headlines have been clear in assigning blame:

- Two girls died looking for a toilet. This should make us angry, not embarrassed

- How A Lack Of Toilets Puts India’s Women At Risk Of Assault

- Toilet Shortage in India Fuels Rape as Women Are Prey Walking to Wheat Fields

Toilets. That’s what we were told was behind the horrific rape and murder of two teenagers in Uttar Pradesh last month. The girls were reportedly attacked when they went outdoors to relieve themselves, since they lacked toilets at home. Understandably, journalists and activists have focused squarely on the relationship between a lack of sanitation and an uptick of violence against women.

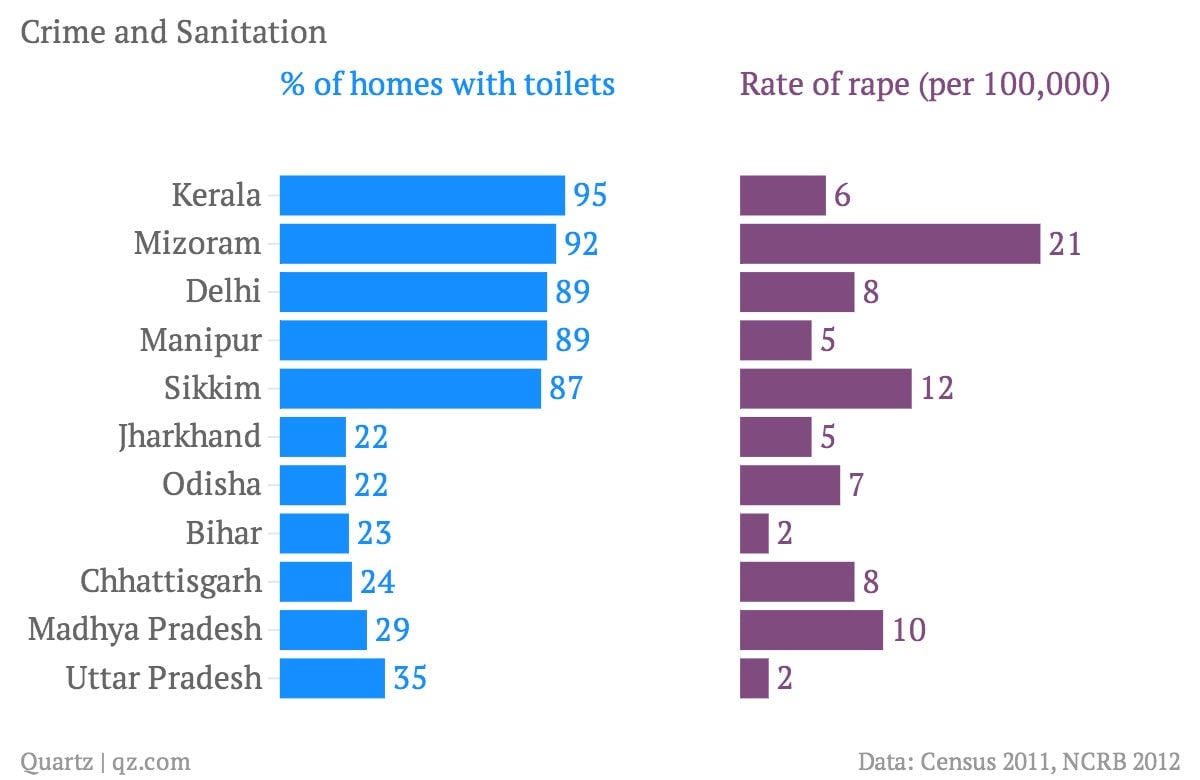

Thus, if a toilet shortage is fueling rape in India, then their presence should lead to lesser crimes against women. But data analyzed from the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) show that there is no inverse relation between rape and toilets. Quartz India compared the states with the highest and lowest toilet density against their rates of rape, defined as those reported per 100,000 women.

The state of Mizoram has one of the lowest number of households without toilets. Yet, the rape rate against women remains a stubborn 21, much higher than the national average of 4.26. Meanwhile, only 20% of households in Jharkhand have a toilet, but its rape rate is one-fourth of Mizoram’s.

Why do some of the less developed states have lower cases of sexual assaults? The most obvious answer is that most women in these states do not go to the police and the crime goes unreported. Even in Uttar Pradesh, where violence against women is reported almost daily now, the annual rape rate against women is less than half the national rate.

The other explanation for the statistical disparity is that toilets have little to do with crime against women. Women in India are raped everywhere: in fields, in moving buses, in taxis, in schools, and inside their homes. While proper sanitation is crucial, it cannot solve India’s rape problem.

Activists fear that by exaggerating the role that toilets played in the rape in Badaun, Uttar Pradesh, other problems might get a pass. Yet they very much exist and need to be dealt with, police reforms to gender equality.

Another problem with linking indoor toilets to safety is the assumption that women are safe inside their homes. But women are more often than not victims of brutal violence committed by family members. In more than 98% of the rapes, the victim knows the offender—usually a relative, neighbour or a friend, according to NCRB. And the debate also dilutes one of the biggest battles feminist are fighting in India: women’s right to go outside and access public spaces— without fear or blame.