These revealing charts tell the real story at India’s big five IT companies

The joke about Indian software companies used to be that without a name board outside, you would be hard pressed to distinguish one from the other inside. They made similar pitches to their customers, employed similar people (who often moved from one company to another) and did similar work. If something hit company A, a strengthening of Indian Rupee against the US Dollar, for instance, analysts knew it would similarly hit company B and C.

The joke about Indian software companies used to be that without a name board outside, you would be hard pressed to distinguish one from the other inside. They made similar pitches to their customers, employed similar people (who often moved from one company to another) and did similar work. If something hit company A, a strengthening of Indian Rupee against the US Dollar, for instance, analysts knew it would similarly hit company B and C.

When financial crisis dampened the demand for IT services, India’s top five IT exporters reacted differently. While Infosys and Wipro struggled, Tata Consultancy Services, Cognizant and HCL Technologies seemed to have a great time.

Here are six charts that explain what happened.

TCS: Turning 1 Goliath into 60 Davids

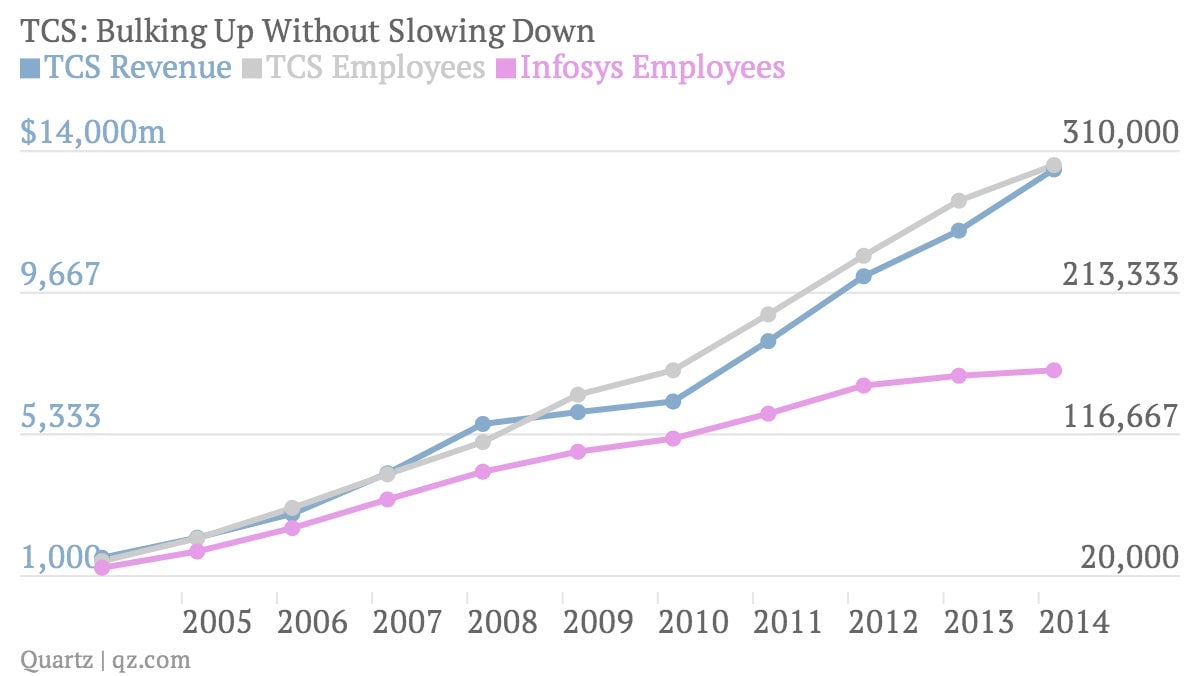

Tata Consultancy Services, India’s largest IT exporter, is a Goliath. With over 300,000 employees, it is the largest private sector employer in India, and the third largest tech sector employer in the world after IBM and HP. It has 78% more employees than Cognizant and 87% more employees than Infosys, the next two in the pecking order of Indian IT—by no means small organizations themselves.

Its headcount growth trajectory changed in 2010, until which its charts ran more or less parallel to its peers. After that it zoomed. What happened? N. Chandrasekaran, the hard driving CEO since 2009, divided the company into 60 small units, with 3,000 to 5,000 people each.

It was a masterstroke. TCS could now add more and more people—which is still the best way to add revenues in an outsourcing firm. And at the same time, it had some elements of a smaller company. The leaders of the units felt a sense of freedom. They could react faster to market needs and pursue big opportunities. It worked.

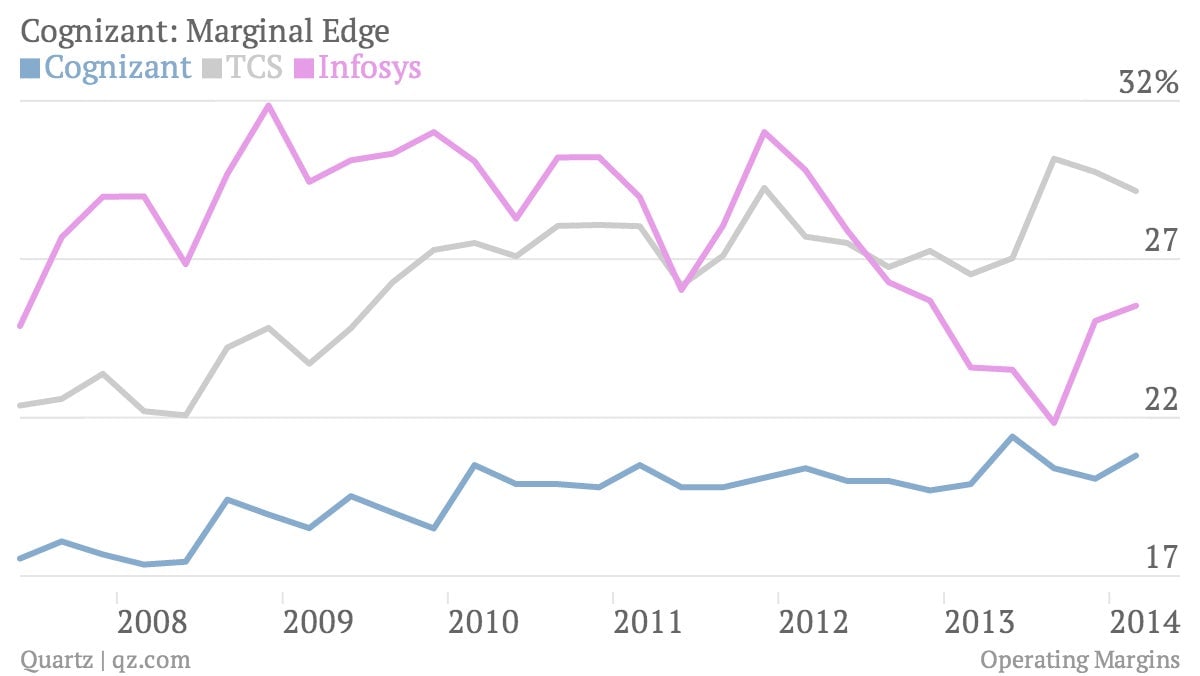

Cognizant: Consistent low-margin strategy

Cognizant operates at a lower margin compared to its peers. Even prior to its initial public offering in the late nineties, it told investors that it would maintain its margins between 19-20%. It has been doing that consistently. The variance for TCS and Infosys, in the chart above, are 5.54 and 6.81 respectively. For Cognizant it is 1.16.

This consistency helped Cognizant in two ways. One, since billing rates and its software production costs were similar, lower margins simply meant it had more money to invest in marketing. It had more executives in the market (US accounts for a bulk of its revenues) who spent more time with clients looking out for new businesses and extracting more revenue from existing clients.

It also gave the company an uncluttered strategy during the financial crisis when most clients were considering cutting IT spends. It continued to spend on marketing through the crisis—and came out of it with bigger share of the market, overtaking Infosys.

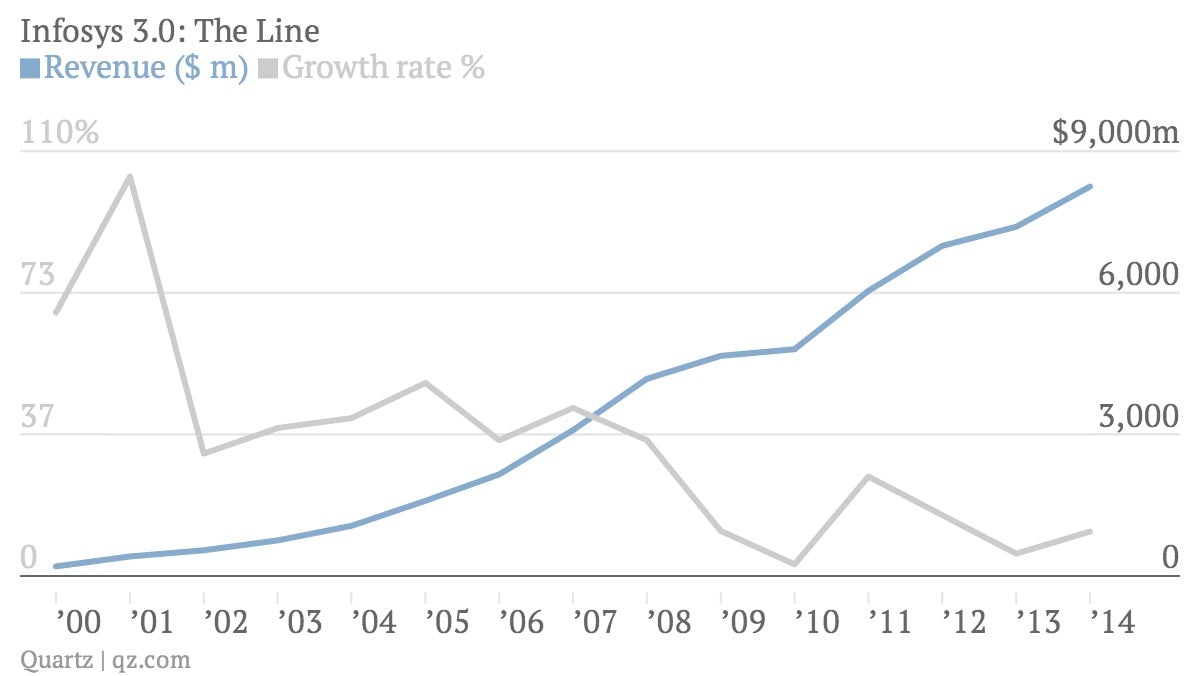

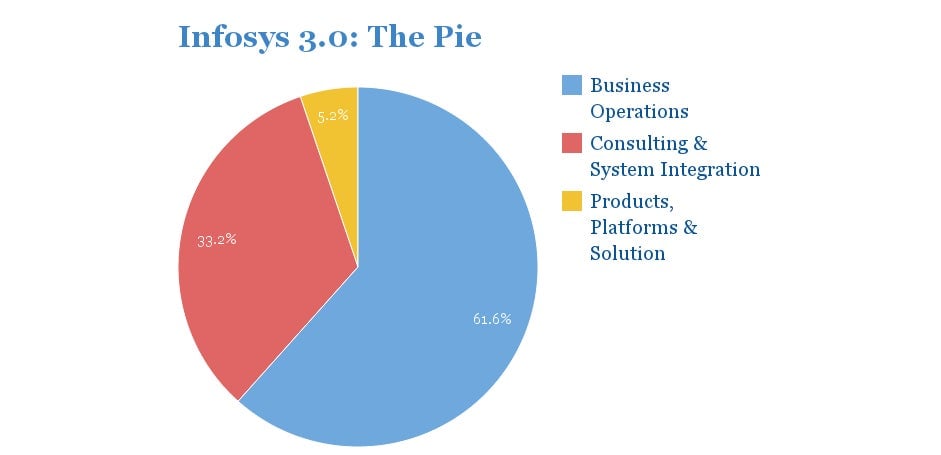

Infosys 3.0: Worshipping at the altar of tomorrow

If you read the extensive speeches that S.D. Shibulal, Infosys CEO, gave when he introduced its new strategy to investors and analysts, you will be familiar with Infosys 3.0—the notion introduced by the new CEO as a way to think about the new Infosys. The first 20 years, or Infosys 1.0, it was busy honing its ability to write codes for customers in different time zones. During the next ten, Infosys 2.0, it scaled up by pursuing deals in different industries. And Infosys 3.0, starting around 2010, would, the company said, transform its customers’ businesses through IT. Its tag line was “Creating tomorrow’s enterprise”. This was meant to help the company grow faster than industry while maintaining its large profit margins.

But many within the company thought of Infosys 3.0 as if it’s structural. It was all about products, platforms and solutions, a part of its business that accounts for just about 5% of its revenues now. This division is focused on building digital services such as Airtel Money. And some executives included consulting to that portfolio.

This confusion told on its sales. As executives tried hard to pitch the customers to create tomorrow’s enterprise, they dropped the ball on today’s. Its bread and butter business of business operations suffered, slowing the company down.

Things changed after founder N.R. Narayana Murthy came back last year. He made Infosys 3.0 less abstract, and defined it in terms of cost cutting, sales effectiveness and delivery effectiveness—and brought in a new CEO whose views on the disruptive nature of software might resonate better with the customers.

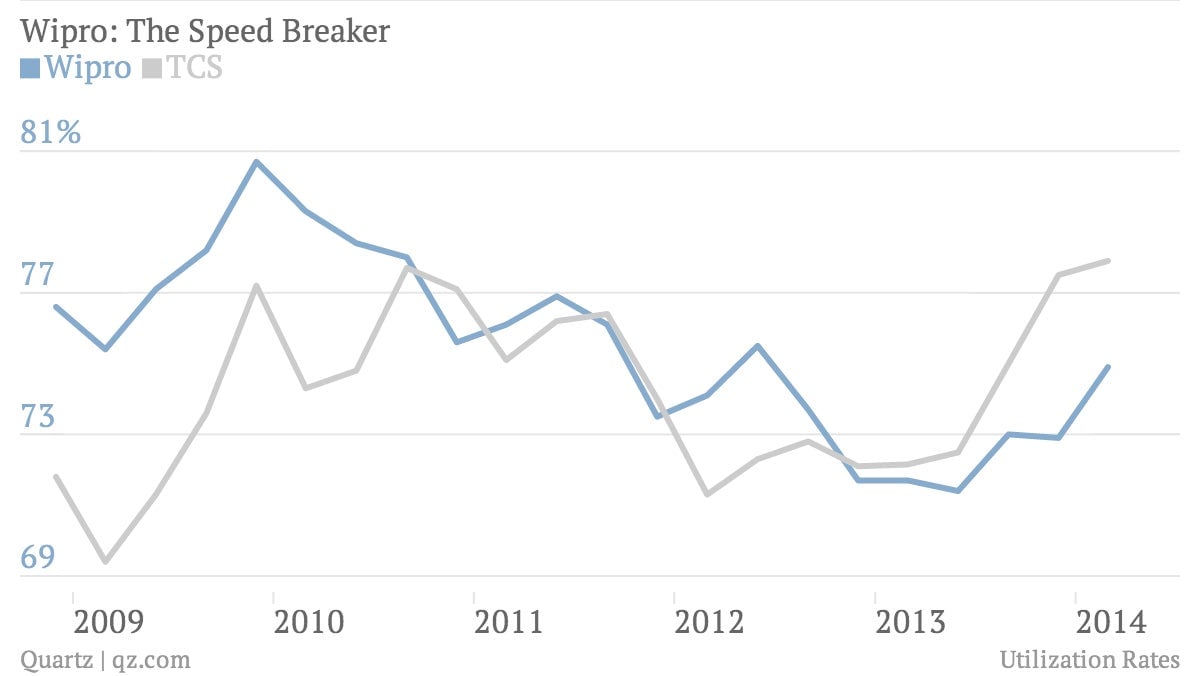

Wipro: Lost Momentum

In 2009-10, Wipro was deploying pretty much everyone it employed in various projects. Its utilization rate (including trainees) crossed 80%, and its rates not counting the trainees was close to 85%. (Utilization rate represents the percentage of employees who were billed for various projects. The actual number might be even higher because companies deploy more people for contingencies).

Having a high utilization rate might appear to be a good thing, an indicator that it’s using people efficiently. But an IT company is not like a hotel—where the number of rooms are fixed. IT companies need people on the bench to demonstrate that it can deliver new projects. During its high growth days, Cognizant had utilization rates hovering around 50%.

Wipro’s high utilization rate around this period was no accident. As the financial crisis struck, Wipro correctly predicted that the demand will fall. It acted fast, decided to be prudent, cut costs, hired less and even shrank the recruitment team.

However, it turned out that demand for some parts of IT services never waned (healthcare, for example). And the growth eventually came back. While other companies were in a position to capture that, Wipro, focused on running a tight ship, couldn’t.

Wipro chairman Azim Premji brought in a new CEO who has since brought utilization rates down to the level of its peers, even as he attempts to get the growth on track.

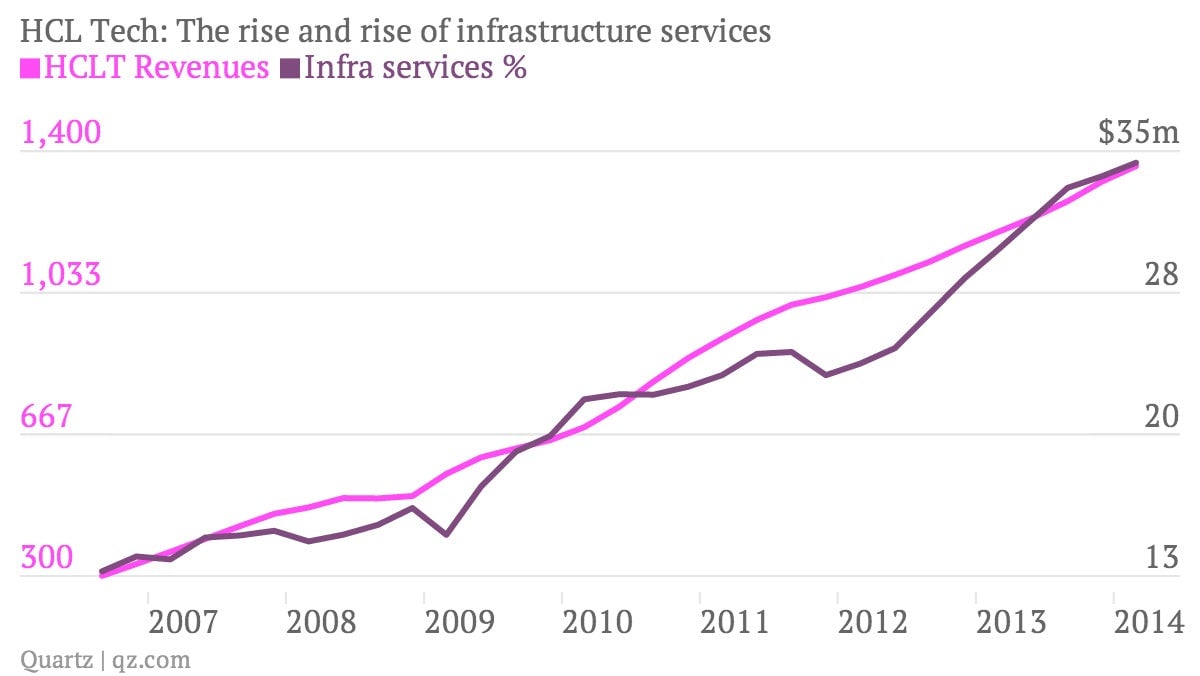

HCL Tech: Focus on the machines

From 13% of the total revenues in September 2006, Infrastructure services grew to contribute more than a third of HCL Tech’s revenues by March 2014. Along the way, it drove the company’s growth and its share prices (up by over 370% from then).

Two things helped HCL Tech in this journey. While Indian IT services companies mostly ignored infrastructure services (the business of supplying and maintaining IT hardware) because of its low margins, former CEO Vineet Nayar knew a thing or two about its potential. He had incubated HCL Comnet, a remote infrastructure management company, back in 1993. Besides, he didn’t have to worry as much as others did about its margins because around 2006, HCL Tech’s margins were even lower than what infrastructure services promised.

Secondly, a large number of outsourcing deals came up for renewal in the last few years—mostly in infrastructure services segment—and none of its peers showed as much aggression as HCL Tech did to capture these deals.

There’s some steam left in both infrastructure services—even though the competition is increasing too—and in the rebid/renewal business. The new CEO Anant Gupta is as committed about these, having headed infrastructure services earlier and having been the part of growth under Nayar.

You can follow Ramnath on Twitter at @nsramnath.