You can blame India’s courts and media for encouraging the national pastime of being offended

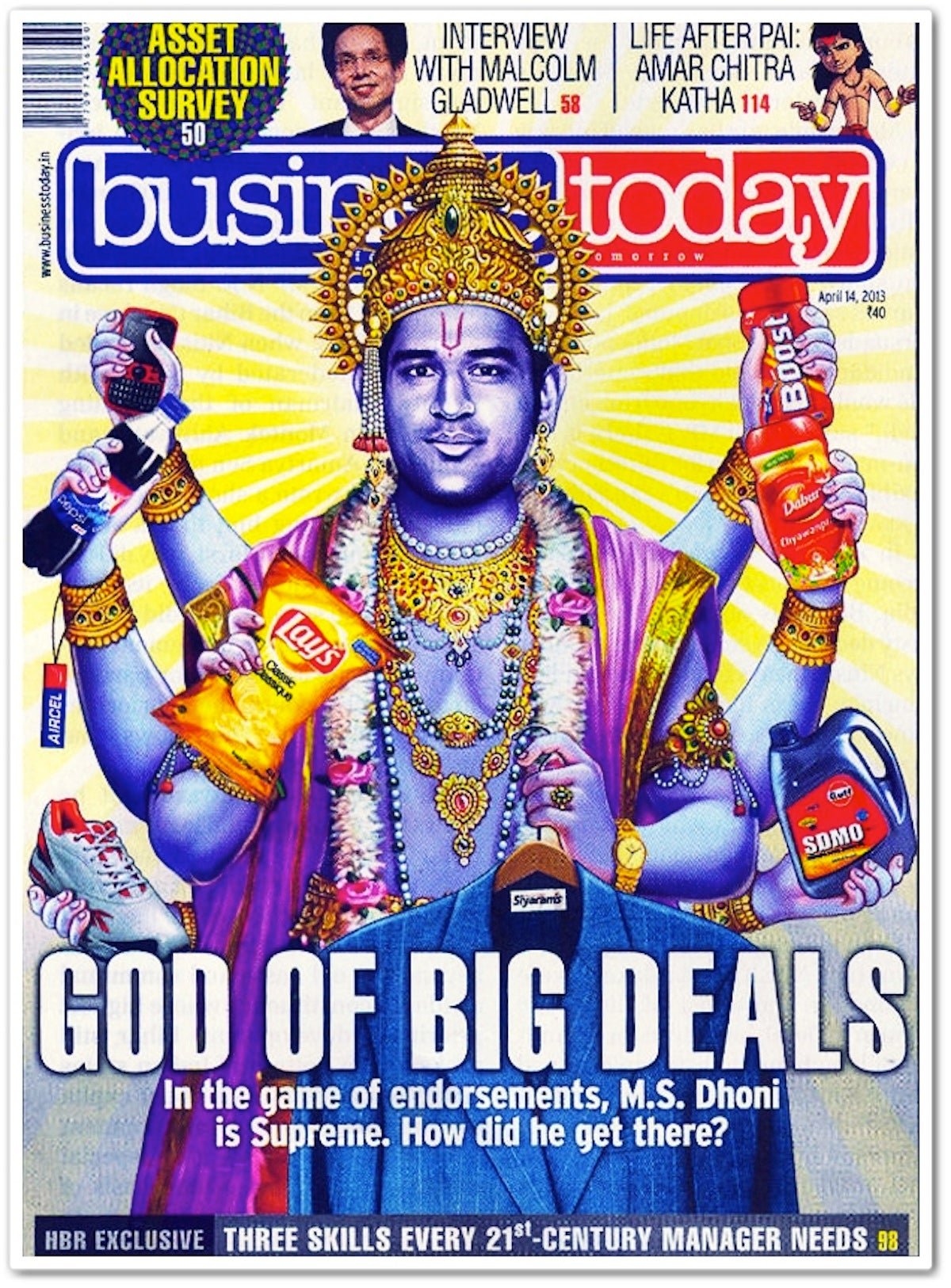

An Andhra Pradesh court recently issued an arrest warrant against cricketer Mahendra Singh Dhoni in a case registered against him for appearing as Lord Vishnu on a magazine cover (it was a Photoshop job—Dhoni was not a party to the action). The arrest was ordered because Dhoni ignored earlier summonses, and not for the alleged offence, but the fact that such a case was entertained and that Dhoni was made a party to it is something that deserves comment. There have been innumerable such instances where some representation in media—be it a piece of advertising, something to with a film (song, scene, title, dialogue, poster), anything a celebrity might have said or anything or anyone the celebrity might have been photographed with, a cartoon in a newspaper, a post on social media (even liking someone else’s post on Facebook) or as in this case, a magazine cover, causes offence to an individual or set of individuals who act upon it in various ways (beating up somebody, attacking the office of the offending organisation, venting one’s feelings on social media or as is increasingly popular, going to court).

An Andhra Pradesh court recently issued an arrest warrant against cricketer Mahendra Singh Dhoni in a case registered against him for appearing as Lord Vishnu on a magazine cover (it was a Photoshop job—Dhoni was not a party to the action). The arrest was ordered because Dhoni ignored earlier summonses, and not for the alleged offence, but the fact that such a case was entertained and that Dhoni was made a party to it is something that deserves comment. There have been innumerable such instances where some representation in media—be it a piece of advertising, something to with a film (song, scene, title, dialogue, poster), anything a celebrity might have said or anything or anyone the celebrity might have been photographed with, a cartoon in a newspaper, a post on social media (even liking someone else’s post on Facebook) or as in this case, a magazine cover, causes offence to an individual or set of individuals who act upon it in various ways (beating up somebody, attacking the office of the offending organisation, venting one’s feelings on social media or as is increasingly popular, going to court).

Part of the reason for this epidemic of prickliness is the vagueness of many parts of the statute that leave an opening for judges across the country to interpret the law in their own ways. Once the door is opened to legal action on account of someone’s “sentiments being hurt,” making distinctions between different forms of offensiveness becomes tricky. If something becomes offensive simply because someone has taken offence to it, then by definition anything accused of being offensive is in fact offensive. Causing offence to someone is a cultural infraction more than a legal one. Cultural transgressions are a function of the receiver’s reaction in most cases. The shift in focus from an action found illegal to a reaction of outrage makes no representation safe from the accusation of being offensive.

In any case, we live in a world where saying nasty things about someone publicly is much more acceptable than it ever was before. Social media, some would say exists for the express purpose of manufacturing offence on a mass scale with both economy and precision. The cyber air is thick with insult and abuse; never has so much hate been generated with such few characters. On Twitter, only the thick-skinned survive. Anyone who receives any media attention has no choice but to get used to the idea that people will find a way to criticise them. At one level, it would seem that causing offence has become more an everyday kind of pastime, something that could be listed on one’s resume.

Then why is there so much more prickliness in the world today than earlier? And it exists across ideological divides—there is as much touchiness about politically incorrect representation about race, gender and sexuality as there is about religion and identity. Making any statement on a contentious issue carries with it a guarantee of receiving feedback full of abuse, anger and derision. People are offended easily and outraged frequently and now have a way of communicating their feelings with pithy directness.

Perhaps being offended is a new status symbol of a kind. It is a sign that the person offended takes himself or herself seriously. Being offended is a sign of strength, and the desired outcome is that the other person’s voice be stilled. In a lot of cases offence is taken to things very few people have seen or indeed are in the danger of seeing. A vastly higher number of people know about the Dhoni Vishnu cover because of the controversy rather than because of the original magazine. If indeed offence had been taken, the instinct would have been to stay quiet or try and persuade the magazine to withdraw the issue. Instead, what we have is a court case and that too involving Dhoni, who has nothing whatsoever to do with the production of the cover.

Apart from chasing publicity, which is an obvious and important end, the need is to make a statement about the strength of the collective claiming offence. The desire is to attack what is seen to be the temerity of anyone to say anything that might be construed as an insult to a group that wishes to display its power. Filing a case is a form of teeth-baring that a group indulges in to ward off any attempts that are made on its perceived territory. The cultural object in question is claimed exclusive ownership of and the right to speak on behalf of the cultural cohort is appropriated. The insult is first identified and then magnified (‘Islam is under threat’, “they are insulting our proud heritage’, ‘the national flag has been insulted’, ‘our gods and goddesses are being defiled’, and so on). The identity of the group claiming to be insulted is sought to be cemented by inventing enemies. By claiming offence, an attempt is made to rally the collective by making it appear as if the cohort in question is under attack. Fear is built around any future representations leading to a form of self-censorship. Over time, some positions become citadels of hateful certitude that brook no discussion or in some cases, even allusion—they simply cannot be spoken of or represented by those deemed outsiders.

The fact that we live lives that are mediated by media makes words that much heavier. Words and images are the weapons that are used most commonly given that today practically everyone in the world is heavily armed in this respect. Control over what other people are able to say becomes vital in a time when so much is determined by the representation of reality rather than reality itself. Offence is the protective shield that is worn on top of some collective identity and the symbolic is experienced as real. Cultural interactions have multiplied dramatically, and taking offence is a new form of currency.

Politically, there is little to gain by standing on principle and a constituency to gain when giving in to claims of being offended. Which is why there is such little interest in upholding the ideal of the freedom of expression. Media, too, is a party to this in two ways. One, by giving any and every fringe group that protests about something coverage without any discretion. And two, by itself engaging in a penetrating search for instances where offence was caused and amplifying these. Even the judiciary has on more than one occasion contributed to the huffy carnival of taking offence. As a result, the offence industry is thriving, with nothing to retard its progress.